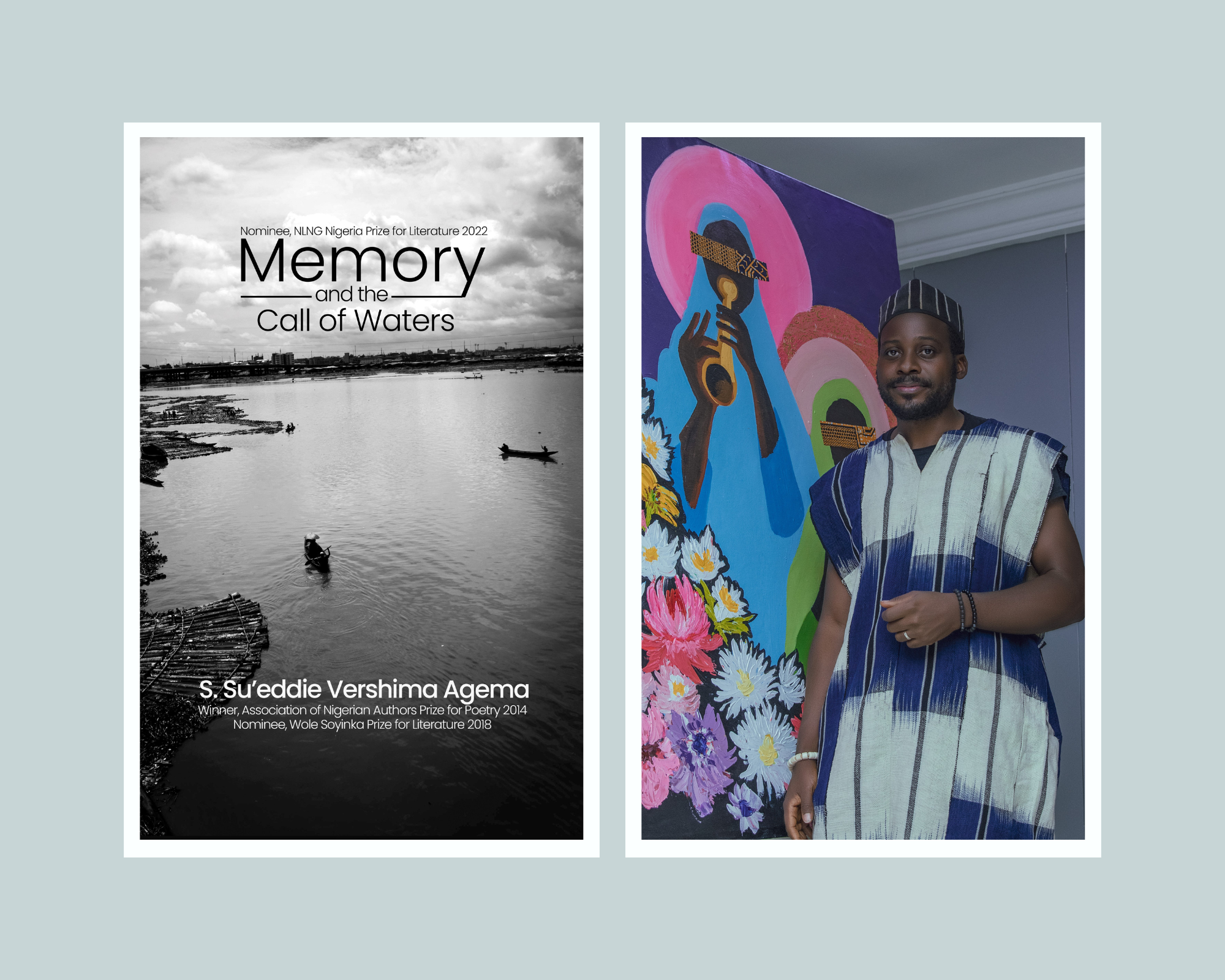

Of Memory and Call of Waters

The earth’s hunger is eternal Its stomach swells with our loved ones In farewell, we make concrete beds And mound pillows… Transition (page 25)

In Su’eddie Vershima Agema’s Memory and the Call of the Waters, memories are tenderness and sorrow. It is a stream of calm waters waltzing through terrains of hurt and loss. It is personal as it is collective. It is honest and probing. It is questing as it is certain. It is vulnerable, packing into 97 pages a journey through very many lifetimes, and other notable places.

The roads memorialized are familiar in material ways, as are the bodies of water that fuel the writer’s muse. Even this style of recounting lived memories is common to my generation of writers using poetry as a vehicle for both documentation of personal journeys and a kind of catharsis — a public record of private thoughts and encounters. It is also a style that is endearing in its relatability. The reader becomes the poet-persona, and the encounters derived from personal contact become a shared communal experience.

Reading through, we know that we have been here before — the landscapes are those we have embodied. But in some ways, we also haven’t. Agema’s words are his own. The experiences we recognize as part of the unending cycle of hurt and disappointments we have lived through as citizens and as readers of this Nigerian space, but parts of it are uniquely his, from Benue to Brighton. What we share, we enjoy; and what we do not, we merely watch along.

The River Benue plays a big role, as is the memory of his mother. Sometimes, the roles they play overlap in the care of the poet looking back from a faraway place on an immediate circumstance. The familiarity of home comes to either soothe, reassure, or bewilder.

The transitions are not always orderly, either, owing to the disparate origin of each experience. One moment, we are mourning with the writer the personal losses he had encountered on a personal level, and in another, we’re sharing a public encounter with bird poop. The connecting thread is the journey, to places where the poet’s feet have taken him in search of succor.

There are names of people lost to time and circumstance; particularly Nigerian circumstance: Ify Agwu, Pius Adésanmí, Fr. Felix Tyolaha, Fr. Joseph Gor, the girls in FGC Yauri, the Chibok Girls, the victims from Ethiopia Flight ET302, the poet’s mother, and many more. He weaves these stories through his own lens, sometimes of nostalgia, and sometimes of missed opportunities. Actually, the Nigerian circumstance most dominates the work, along with the hurt and disappointments that have attended a citizen’s expectation of normalcy. There is a lot of death and destruction in the poet’s gaze as in ours, and the landscape is what we have known only too intimately.

Show me this darkness, Lord Eating the light of my eyes… (The Cloak of This Present Darkness, 46)

The influences are diverse too, from the clear lucid lines bearing all the melody of mourning, to sometimes inscrutable verses clearly encoding personal experiences shared only with a few close friends, and locked away from the reader’s gaze. All find their place in the wide breadth of our poetic universe.

Where the voice is most memorable, the writer is introspective, seeking clarity to certain cosmic directions.

There is joy, in places, tentative and pensive. But the morose overwhelms, just not in a way that dampens the spirit as much as it gives it space to breathe and to feel each dimension of its presence. It is not, in its core element, a sad book. Nor is it a happy one. It is just a record of moments that define the writer’s flights of fancy over many years and many places, where magic often happens, as well as other dimensions of wistfulness.

I wait for the angelus bell to ring It does not remind the faithful to pray It reminds me of your transition through their swords *** I raise a dirge of too many memories filled with holes, Waiting to be parched when I become the earth. (Transition II)

I enjoyed the poems and the tenderness with which Agema bares his soul. It is a lovely book. It adds to the many records we have of this generation’s grappling with the quotidian issues of the times, in their own way, and in their own voice, pulling a myriad of influences to the service of personal and collective memory.

Memory and the Call of the Waters is one of the three shortlisted collections of poetry in the 2022 Nigeria Prize for Literature.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún is the Publisher of Olongo Africa.