“My life has always been based on very deep convictions” || Wole Soyinka in Conversation

In February 2024, we sat with Nobel Laureate Wọlé Ṣóyínká as part of the production of Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory — a documentary biopic that examines a location at the University of Ìbàdàn where he lived briefly when he was appointed as the first Nigerian Head of the School of Drama. It was from there that he was arrested after visiting Biafra. A little bit of this interview, conducted by Dèjì Tóyè already appears in the film, which premiered in July of that year when Ṣóyínká turned 90. But for the first time, we make the full text available here to mark the writer’s 91st birthday in 2025, especially because parts of it that didn’t make it into the film are quite illustrative of Ṣóyinká’s life and journey as a literary icon, national figure, activist, humanist and conservationist. Transcripts of all the other interviews in the film, along with their unabridged recordings, are accessible at University of Pennsylvania, Northwestern University, and Indiana University libraries.

You can rent/watch Ebrohimie Road now on Vimeo.

*******

So the first question I want to ask is this: the Ebrohimie Road house in the University of Ibadan, did you choose the place, or how was it allocated to you, especially considering that it abuts a forest? Did you choose the location?

I not only chose it, I campaigned for it. I lobbied for it. I cheated for it. I beat people up for it to make sure I had that particular house, anything it took.

Right now, we are here on the grounds of your current home, and we’ve also visited your former residence in Ìbàdàn, even though some portions of the land have been encroached upon. But we noticed that there is a tendency for you to want to live very close to nature. How did that come about, wanting to live in a place that is very close to nature, particularly to the wilderness?

Wilderness? No, I don’t consider forests wilderness. It’s my home. It’s a difficult question you asked. How does one develop preferences, not just preferences, but move into options as if it’s the most natural, obvious thing in the world? All I can say is that, well, I grew up in a parsonage, which is very wooded, with rocks, trees, and all kinds of vegetation. My father was also a horticulturist. He was very fond of roses, but as you see, I’m not particularly interested in flowers as such. I just want the raw nature, as sumptuous as possible. Somehow, I used to follow him anytime I could get away with it. I’d sneak up behind him when he went for his walks in the bush, which is usually to hunt with a small air rifle. But, for me, it was just the most natural thing in the world, so it’s difficult to explain. That’s the way I grew up, actually wanting to vanish into the wooded areas.

What are your most significant memories of living in that house at that time in Ibadan?

Well, that’s one of the easiest questions to answer. The most dramatic and significant achievement of Ebrohimie Road was that it was from there that I went into detention, and it was back there to which I returned. So it covers both a period of absence and a period, of course, of intense activity, in terms of political activism, etc. It became a sort of center for quite a bit of my activities, yes.

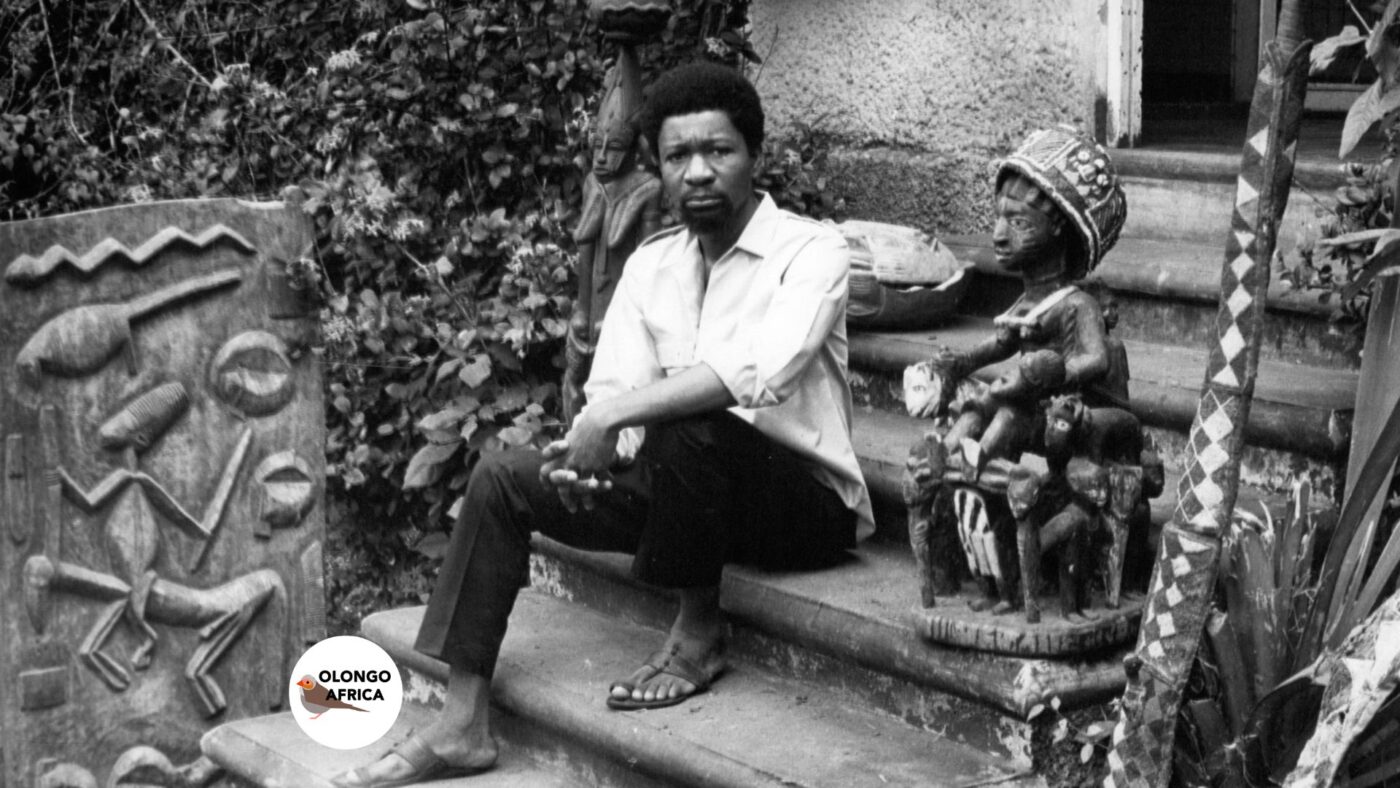

We’ve seen some old video news clips of that time, especially the interview you granted when you returned from detention on the terrace of the house. We also saw that you stacked most of your artwork in the garage and some by the door side. We, and those who have also interacted with you in this new home, see that art surrounds you. So, what was the relationship between you and your art in that place, especially when you had to stack a significant portion of them outside of the home itself? How was that for you in terms of the use of space?

How did the yearning to collect artworks begin? That I can specify. Some artworks were stolen, sometimes by expatriate staff within the university itself. And I became conscious of a heritage disappearing. It was a free-for-all, literally, and wasn’t just in the University of Ìbàdàn alone. It was happening all over the place. In fact, today, there’s a place in Italy I was taken to, if you see the amount of loot there. I investigated, and they were carried out continuously by one of our foreign construction companies. Imagine coming from outside and looting from all over the place. Well, the impulse came that at least I wanted to, one collaborate with others to stop the exit of this marvelous heritage and two, to enjoy them myself without having to go into the museum. From excursions to museums, I developed a kind of affinity for artworks, especially traditional carvings, because that’s really where I started.

Then there is also an important relationship for me between nature and artworks, perhaps because I grew up with a sensitization to the fact that nature offers the primary impulse for creativity. That might seem a rather loaded expression, but then what does one wake up to? Nature, in most cases. It’s different now, of course, if you are born into urban overgrown areas, but traditionally, in rudimentary society, what does one wake up to? What is one born into? Nature. And so, what does one begin with when the instinct to represent reality overcomes somebody with an artistic instinct? To represent nature, to bend nature in creative directions, and so on and so forth? So, I’ve always considered creativity itself as part and parcel of one’s relationship with nature. So it could be that combination that fulfilled me and made it the most natural thing in the world to turn my garage into a small gallery, as well as my study, surrounded by these products of other creative minds. I had a kind of affinity with the process of creativity itself.

Thank you very much. I don’t know the last time you visited Ebrohimie, but I’d like to show you a picture. Firstly, we’d like to see your reaction to it, and then I’ll ask a question. So you see that the house itself is on the bottom left. And then you’ll see something very significant, a white structure on the bottom right. We understand that it used to be part of the grounds of the house itself, but obviously, it’s being ceded out to some bank that built that structure, cemented the frontage, and then fenced the road. What do you feel about this?

Disgruntled. I never understand why, if it’s not absolutely necessary, one should even encroach on nature or green. I think the green surround is so elementary to human existence that the instinct should be to, in fact, demolish structures to have the terrain repossessed by nature; that will be my immediate instinct. But unfortunately, the development is seen as being primarily nature destruction with certain kinds of temperaments, mentalities, and institutions. It’s a great pity; it’s always that place. It’s like me having my head shaved bald like yours. And that’s not a comfortable feeling. So I have always moved when a situation arises anywhere I have stayed where the institution feels it must encroach on nature. I tend to move out and look for a new place to live, even if it’s outside campus, even if it has to be outside campus.

I think we’ll return to the last bit you said later, but I want to find out about Ìbàdàn itself. Most people don’t know that before taking the job in Ìbàdàn in the School of Drama, you also had a short stint at the University of Lagos. Why did you decide to take up Ìbàdàn and not remain in Lagos?

Well, Lagos was becoming overgrown. By that, I mean overgrown by buildings, by structures… Normally, nobody really quarrels with the principle of physical development, but it was getting choked. And, in fact, I didn’t live on campus when I was teaching in Lagos. It wasn’t sufficiently wooded, so I found a place in Igbóbì. I actually stayed in Igbóbì, not far from campus. The place where this young man, the choreographer and dancer, has his studio, not far from campus. I’ll remember the name in a moment. I found a marvelously wooded place, and that’s where I stayed throughout the time I was teaching in Lagos. But, eventually—I was teaching then, of course, in the English Department—and when Geoffrey Axworthy, who was the first director of the School of Drama, left, I applied for that position. And I was absolutely overjoyed when I got it. And of course, the first thing is to start looking for a wooded environment to live in.

I think it was Bariga, sir. Or Akoka

Yeah, Akoka, but Bariga is also around that area.

You are trying to recall Ṣeun Awóbánjọ, right?

Adéfilá…Ṣẹ́gun Adéfilá.

Thank you very much. Ultimately, you had to leave—of course, we will discuss shortly some of your activities in Ìbàdàn—sometime in the early 70s, after returning from detention. Many people have different theories of why you left. You had the fellowship in Cambridge; there was also the trauma of what you had been through, and maybe your ability to fit into the environment. Now there’s a third theory. I won’t mention who said this during our interaction: that, especially considering that you later returned to Ifẹ̀, you probably had an issue with the kind of university system that Ìbàdàn had; that you didn’t seem to have that scope to do what you wanted to do with the School of Drama, particularly because of the kind of things you later did in Ifẹ̀. So, what was the strongest reason you had to leave Ìbàdàn.

I found I had to quit Ìbàdàn for many, many complex reasons, the most important of which is that I wasn’t just leaving Ìbàdàn; I wanted a spell away from Nigeria. It was postwar, and the atmosphere of triumphalism was so blatant. It was like, “Oh, yes, we are the victorious people, the Federal side.” Biafra was devastated. And while—we must always emphasize this—many areas, especially institutions like the University of Ìbàdàn, made the returning Biafrans welcome and actually tried to put them at their ease, which was very commendable, generally the overall reaction, even within campus itself, especially among the rabid federalists, just sickened one, because one knew, at least I did, that that war was not over. The struggle on the battlefield was over, yes, but the nation had a problem, and that problem was not reflected in the kind of sensibilities I found around me, and so I felt it was time to check myself out for some time, you know, and explore my profession in other areas and develop other interests. So it wasn’t a UI problem as such, although that was a very prominent trigger, in terms of having to encounter people all the time who, if given the chance, would burst into war chants, like “See, we won!” “We’re going to show them we’ve shown them!” And anybody who did not support that national jingoism was considered an enemy of the state, and it is a very repulsive kind of ambience to survive in. And so it was time I took myself off.

Thank you, sir. How would you compare your time in Ibadan and your time in Ifẹ̀? Of course, you probably spent a longer time in Ife, maybe less detention, so you could use the home, or stay home a lot more. But also in terms of the work and academic environment, those kinds of things you’ve spoken about in Ìbàdàn. What’s it compared to, Ifẹ̀?

Well, Ìbàdàn was already formed, so to speak. It already evolved an academic culture, a particular kind of academic culture, with, of course, again, spasms, quite impressive patterns of creativity. There is no question at all that it was struggling to balance academia with creativity. Ife was a new organism, which in itself is a creative process. And so it was more adventurous; you could put your stamp on it. And remember that I began on the old site under Bíòbákú before Olúwásanmí took over. But the new site was developed right there on that old site. And I was part of it. I used to be consulted on things including even the architecture, the grounds, trial and error, with a model permanently on the desk of the vice chancellor, etc. So it was creating a new organism, one that was very principled; the standards from the very beginning were placed high. It’s not like today, where, in some cities that I have been to, you have a university here, then there’s a barroom here, and then there’s a mosque there, and then the university there, and then a Christian chapel there, just as you wish. How they get the licenses, I don’t know. But this, at that time, was pioneering in the real sense of the word—exciting, challenging, and accommodating, a collective effort. So that in itself, for me, was a creative engagement.

To close out on Ìbàdàn, did you ultimately regret not being offered tenure in Ìbàdàn? Do you also regret some of the rancor, that surrounded that entire process?

No, but I did have tenure. Remember, I said something earlier about fixed culture, not very flexible, and that affected the regarding of a position, like the Director of the School of Drama, and I found that offensive. So that was, again, part of the problem.

I guess what I wanted to say is the issue of professorship in the department, because I think it transformed into the Department of Theatre. Did that happen in your time?

Yes, it happened. I was the one who created the Department of Theatre Arts. It was originally just the School of Drama. And then we began to—don’t forget, this was a period of decolonization, conscious and fervid decolonization of the curriculum in all departments, but most prominently in the arts—so with the School of Drama being a creative institution, to begin with, I began to consciously inject more academic pith into it, creating various disciplines within the dramatic act itself. So, in other words, the School of Drama already existed. Now, because there was a kind of patronizing approach in the many other departments towards the arts, it’s sort of mentality of “àwọn agbégijó náà ni, so what are you fussing about?” We had to teach them that it’s a very serious discipline, which involves history, critical analysis, philosophy, and, sometimes, even archaeology. So we started transforming the department. But the, shall we say traditionalists still couldn’t come to terms completely with the fact that when you talk about the dramatic arts, we’re talking about a full-fledged academic discipline, in addition to, and as part and parcel of, the performing arts; they just couldn’t get into their head, so it was a kind of patronizing attitude. I could live with that, but, ultimately, the attraction when I came back was the possibility of participating with a new organism.

Thank you very much. Okay, so I want to backtrack a little to much earlier in your career, when you returned from Leeds and the UK to Nigeria. You did a lot of travel; I think you had a Rockefeller grant to travel across the country and even neighboring countries and then record things about traditional theater performances. I’ve also seen your documentary, and I suppose that part of the things you used in Culture in Transition came from that experience. We’ve spoken to some of our children too, and they said you traveled a lot when they were young. How was Nigeria at the time? I mean, we are talking about traveling now: getting yourself into a vehicle and driving across the length and breadth of Nigeria. How was that sense of Nigerianness, you know, the ability of a young person to just travel all over the place at the time?

I very much pity the younger generation, that they could not do what we did in those days. They could not, just on a whim or simply because some event is happening in Enugu and you are in Lagos, jump into a car and drive to Enugu. You have to plan, you have to be careful, and you have to watch your back today. In those days, you didn’t even give it a thought; night or day, it didn’t matter. You just got up, and then you woke up the following day in a different environment anywhere in the country. So it’s very sad. It’s such a deterioration of the scope of learning, of adventure, of curiosity. It’s a great pity.

Reading The Man Died, one of the things we found out also, in your traveling was that because you were all over the place, you happened upon a particular political crisis that happened in Nigeria. For instance, you happened upon the onset of the pogrom in Kaduna, as the story goes. We’ve also spoken to Mrs. Shadé Thomas-Fahm, who was also involved in the story, but there seems to be some discrepancy about the personalities involved. You mentioned in your book that you were scouting for a location for a movie shoot for Francis Oladele’s film when it happened. Mrs. Shadé Thomas-Fahm believed she saw you with Christopher Okigbo, and that Christopher Okigbo handed her something to give to your wife you know. Now, besides clarifying the situation, can you relive for us how that felt to you, being in Kaduna on a different mission and experiencing that? Of course, you were aware that the political issues were going on, but the idea that you would witness the onset of the pogrom, can you relive that for us?

Well, the political atmosphere at that time was very tense during that period. And there’s actually the friction between Shadé’s recollection and mine. Because after we met and were exchanging memories in the recording, I began to recollect meeting Christopher Okigbo in the north. Because I met him also in Belgium, before he was involved in that plane crash when he was returning from Europe. He didn’t tell me what he was doing, but when that plane crash occurred just before the war started, carrying arms and ammunition, I realized Christopher had been purchasing arms for Biafra at that particular time, which is when I realized that war was imminent and maybe unavoidable. But I was caught in the north, yes, during what was called a minor pogrom, in which the Igbo and any Eastern-looking person was lucky if he or she escaped with his or her life, and I was involved in a number of scrapes, which I barely survived. But not merely in the north; when I was in Lagos, for instance (I wrote a poem about it), with the same Francis Ọládélé, we were going around looking for locations for the film he wanted to do at the time, “Kongi’s Harvest,” and I was trapped around Maryland when the shootout began during an attempted coup. That’s when I wrote the poem “Civilian and Soldier.” I was living in Lagos at the time, so this didn’t really involve Ebrohimie. Ebrohimie came into play some time afterwards.

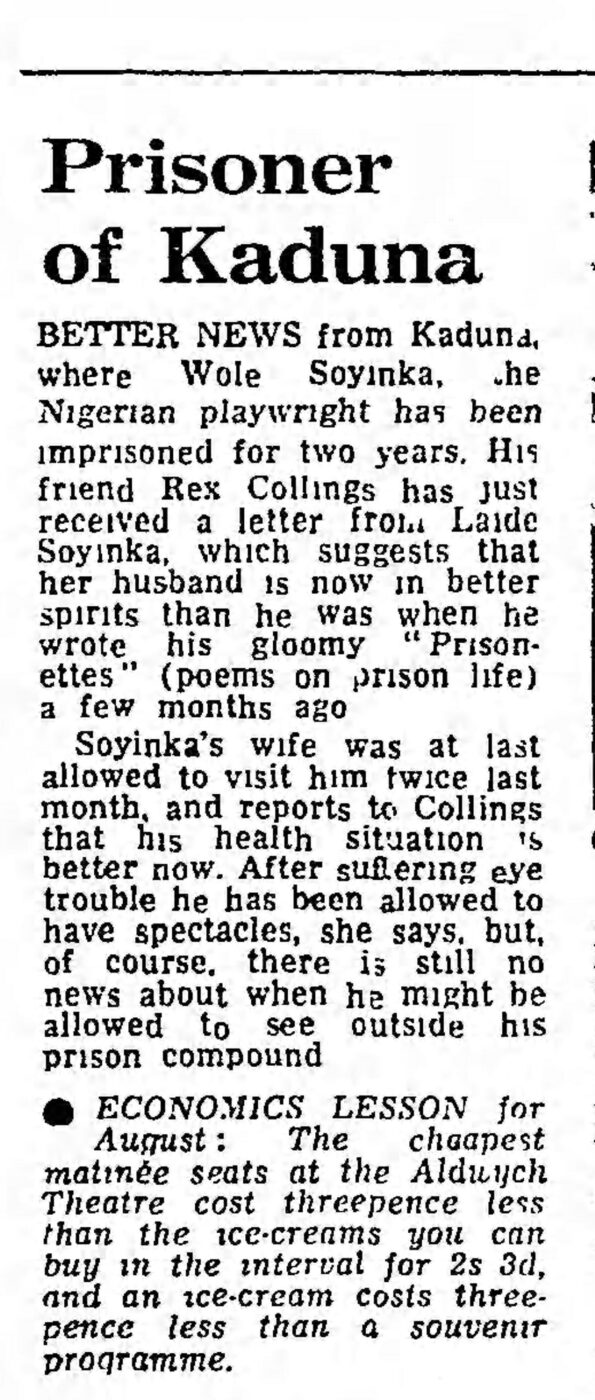

Thank you very much. For most of the time that you were in detention, you were in solitary confinement, and you did say that you were denied writing materials and you weren’t getting the news. But, probably when you came back, or unless something was smuggled into prison for you, did you see the publications that were going on during that time? I could show some of them to you in terms of editorials that were being written in Nigerian newspapers on your activities and the way you were perceived and portrayed to the public by the media, especially after you returned from Biafra. Were you aware of these publications?

You know, even in prison, you can sense hostile emotions and paranoia. You can smell and imbibe paranoia. You can sense collective phobia even behind prison walls, so I didn’t even need to see some of the editorials. As far as the majority of the contributors were concerned, I was a traitor that should have been tried and hanged. No, I should just have been hanged without trial for treason, for being a Biafran, for supporting Biafra, and all kinds of things. One needn’t have to read the material, you knew, you sensed what was going on outside, especially given the circumstances under which you were thrown in prison detention. You could literally read out without seeing some of the writings. Of course, when I came out later, I saw bits and pieces. And then of course, I’d already overcome the waves shall we say, of emotions.

Okay, thank you. Now, talking about your travel to Biafra, you had said jocularly and written, in some certain interviews, that first, you were missing your friends, the Mbari crew and the rest of them, but of course, there was also the more important thing about human issues. Your thinking at that time, have you rethought it? That is, the thing that propelled you to take that decision, not just in terms of the morality of it, but also in terms of the practicality and maybe the rationality of the decision to go by yourself to Biafra, and hope to negotiate things between both sides, have had a chance to rethink about it now?

My life has always been based on very deep convictions. So till today, I have no reason to change my stance. There’s provocation to change that stance because of the stupidity of some of those extremists and fanatics with which one has had to cope with in recent times. But for me, that seems to be part and parcel of human nature: you become a partisan of a cause, for most people, only when that cause seems to be winning. The moment that cause or the proponents of that cause, think they’re losing, everybody becomes an enemy. It’s a lack of a sense of philosophical security that causes people to behave sometimes like ingrates, shall we say?

Thinking about it, you were meant to, or at least planned to, meet some of your colleagues in Biafra. I have read about and heard you talk about your chance meeting with Christopher Okigbo. Which other people did you meet? Achebe? Ekwensi? How did they react to you?

Let’s not go into all that history because it’s not part of the history of Ebrohimie.

Although we touched on it when we started the interview, we’ve also spoken to some of your children about your sense of space in terms of how you’re very particular about spaces, both for living and for working. How does space reflect in your activities, in your writing, in your theater, and in your poems? What do you draw from space?

Now you’re delving into Wọlé Ṣóyínká. I want us to limit ourselves to Ebrohimie House: the things that came from there and what I might have returned to that place. Now you’re delving into the mystery of my creativity. No, I am not going to talk about Wọlé Ṣóyínká that much, only as it relates to that building called the Ebrohimie sanctuary.

Thank you. Still on the issue of space—this also relates to Ebrohimie—and the fact that you chose Ebrohimie, because we were not aware until we asked now and, as you said, campaigned and fought for it, says a lot. Also, the sense of solitude, to be able to live in a place that is slightly removed from the hustle and bustle. You, in fact, said that your not wanting to stay at the University of Lagos was partly due to that. So what, again, is solitude to you? Did you find it in Ebrohimie?

Well, there’s no question at all that compared to other places I have lived, Ebrohimie provided solitude. And I recall sometimes we would rehearse until late in town in the 1960s when I was running Orísun Theatre and so on. Then after rehearsal, we would go to one of the nightclubs, listen to Túndé Nightingale, Orlando Julius, etc., until the very early hours of the morning, to be able to get back, go to bed quietly, wake up, and start working the rest of the day. Ebrohimie was one of those places where I enjoyed that sense of solitude. Perhaps the only comparative residence in my peripatetic existence would be the Ifẹ̀ house, which was also very wooded and protected from the street. After I left there, the next person that moved in began by cutting down the trees. I wanted to cut off his head when I went there and found the trees were gone. But Ebrohimie, yes, that is one of the things I enjoyed there. I could get away from campus, even though it was on campus, on the very edge of campus. I could get in and out the back way without anybody even seeing me.

Yet you currently live most of the time in Abu Dhabi now. I’ve not been to Abu Dhabi, but I have passed through their airports, and I’ve been to Dubai, so I know how those places are. Is there a way you’re able to create that sense of closeness to nature and be removed in a place like that?

It is a different quality of solitude. For instance, my apartment there overlooks as much of Abu Dhabi as overlooks water, artificial lakes, It’s different kinds of solitude, very, very different. The quality is totally different. To be able to get up in the morning and go sit with my espresso coffee until I’m ready to work is perfectly okay. But definitely, my preference is nature. Abu Dhabi is an artificial city, very ordered, very organized, almost clinical in its appearance and in ambience. It does not even remotely approach the quality of solitude that I have here, whether it’s here in this house or Ebrohimie or even Igbóbì everywhere. I somehow always—well, I look for it, but I always succeed—find a place where I can enjoy both: sinking into total obscurity and at the same time coming out when I feel like it; you know, sinking into obscurity with just my work.

I’ve got a couple more questions. We visited Onírèké, and we visited the Cambridge House, where Christopher Okigbo used to live. We interviewed Chief Berkhout, but I want to go back to Fìdítì. You used to visit Christopher Okigbo in Fìdítì, and you had some adventures there, even doing some hunting. Was Christopher Okigbo a hunter as well? Did he join you in some of your extreme adventures of disappearing into the bush? What was his relationship to nature and those kinds of adventures during the Fìdítì time?

I don’t think Christopher went to Fìdítì to be with nature; he just took on a teaching job and wanted a place where he could write his poetry while he was teaching. So I used to pop over and see him and hunt, as you said, and also participate, I must confess, when he stole chickens from next door; that was Christopher Okigbo. He had a method of enticing the chickens into his compound. I confess that I participated in consuming the stolen goods. He used to get into all kinds of trivial mischief like that.

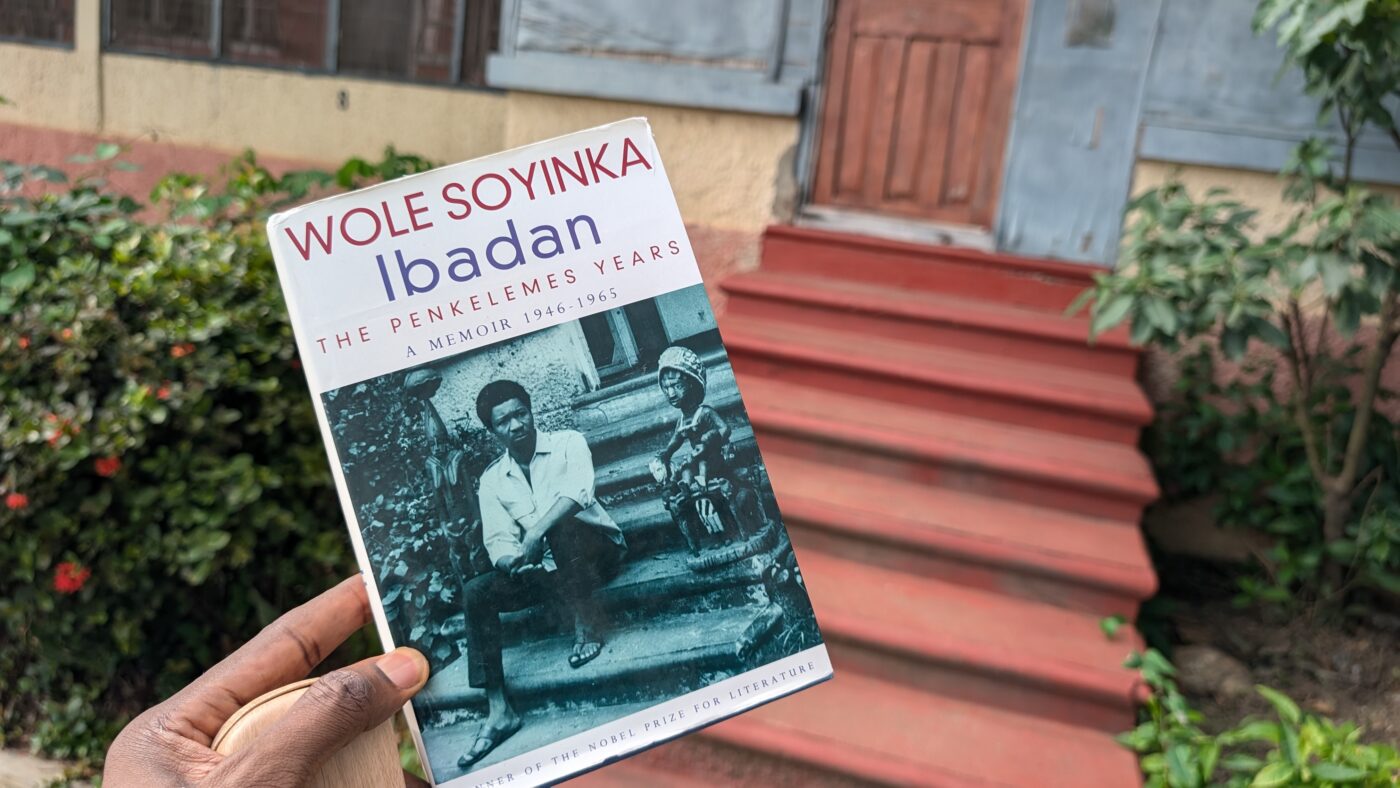

This is the last question. You’ve always threatened or promised not to write a memoir of your adult life. But you’ve written essentially about things that intersect with politics, like Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years (1994) and You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006). But, in terms of your connection to nature and, for instance, being a hunter, who disappears into the bush, are we going to ever get a long nonfiction that just talks about your hunting experience?

No, it’s not likely. I think there’s sufficient corrective material in some of the memoirs I’ve written. In fact, how did I begin writing memoirs? One, I wanted to recapture a certain essence of how I grew up, where I grew up. In fact, I wanted to write the biography of my uncle, Reverend Ransome Kuti, and I warned him that I was going to do that, and he agreed, and then he died on me. And so after some years, I felt I wanted to recapture what it was like growing up in that period, the cusp of independence, you know, the years just before independence, the nature of the very strange relationship with our colonial masters, and how our leaders, our mentors, our elders, managed to find a balance, like somebody like Ransome Kútì, who was a fierce traditionalist, at the same time, a Christian, at the same time, a real English gentleman, and was able to combine all those together. That’s what fascinated me about him.

And then he died. So after that, I managed to recollect that period, and I wrote Aké: The Years of Childhood. Then, as I got more involved in politics and having to cope with experiences, like being locked away while people were fabricating stories about why I was there and how I got there, I said, “Okay, let’s put some things down.” Then it became a habit.

Okay, thank you very much.

_____

Dèjì Tóyè is a Lagos-based lawyer, writer, and cultural advocate. He can be found on Twitter @dejitoye. The conversation was transcribed by Adémọ́lá Adéfọlámí.

Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory was written and directed by Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún with cinematography by Tunde Kelani. It will screen at the Wole Soyinka Theatre, University of Ibadan on July 11, 2025 as part of activities to mark Soyinka’s 91st birthday. More details here. You can also watch it now on Vimeo.