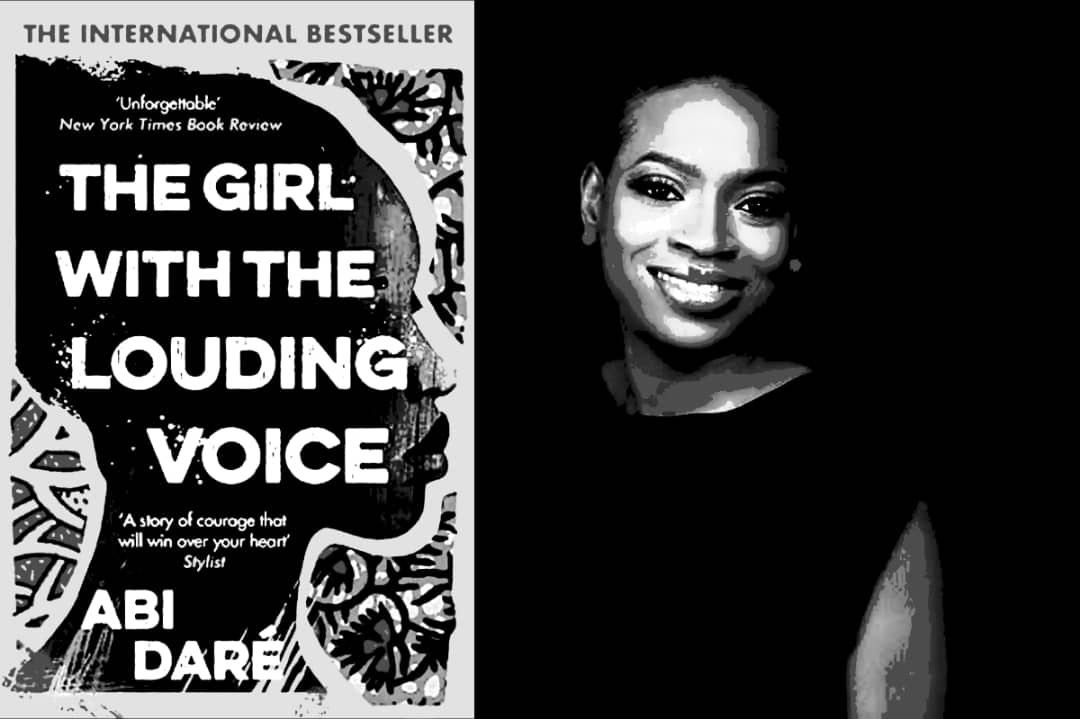

A Chat with The Girl with the Louding Voice

Kola Tubosun (KT): The Girl with the Louding voice, a very fascinating book I read over the last couple of days. I am glad to speak with the writer.

Abi Dare (AD): Thank you, Kola. It’s such a pleasure to be here with you. I’ve heard great things.

KT: I enjoyed the book very much and I hope we’re going to have a lot of very exciting things to talk about. I guess it’s good to start by asking you to tell me about your background and what led you to writing a novel and writing this particular novel.

AD: Thank you for that. I was born in Lagos, Nigeria. I spent the first 19 years of my life there before I came to the UK to study. One thing that was quite common where I lived, I lied in a house in an estate, is that many of the families there had housemaids, girls especially who worked for the family and did most of the work. As a young child, I had lots of questions that I put in the voice because we grew up in a culture where we really don’t question a lot of adults. I had a lot of questions around why many of them were not educated #, why you could tell who the maid was often, you could almost tell who the maid was when they went out to a restaurant. If you were looking at a family of 4, you could tell who the 3 children were and who the maid was. I had a lot of questions but I couldn’t voice them so it wasn’t until I left Nigeria when I had my own children that I had a conversation with my daughter who was 8 years old at that point. I asked her to do some housework in the kitchen, very politely and her reaction was one of ‘I’m tired, I really don’t want to do this’ and I said to her, ‘look, do you know that young girls like you who are not as privileged as you are working for families in Nigeria’ and her reaction was one of ‘what do you mean? Do they get paid? Can you pay me for washing the dishes?’ And so that led into a series of conversations and I said to her, I’m talking about child labour. So that led me to researching, looking at human rights, child labour, watching a lot of videos on YouTube and reflecting on my past. That time, I was doing my M.A. in Creative writing and I was due to submit a dissertation. Before ten, I’d been critiqued quite heavily, nicely but heavily on how I didn’t know quite well how to build a character and I felt I could write this story but I really wanted it to be about the character. Yes, I would highlight the things happening but it would really be the character that would carry the story so that led me to writing the first set of 3000 words and a lot more to, then and then, a lot more and then you have the books in your hands.

KT: Thank you, and thank the child that inspired you to write it. You mentioned something I was going to ask next, your background in creative writing. Did you always want to write a novel? How did you find yourself there and what work went into getting yourself equipped with the literary skills to be able to tell a story?

AD: I’d been writing since I was a child, my mum brought me a family album not long ago and I found that I had ripped out most of the images and had put like speech bubbles above the images and had given them dialogues. I think it has always been in me to tell stories. When I first came to the UK, I think it was the early 2000s or so. I started a blog and my blog was really me just ranting and documenting my life as an immigrant, trying to understand the culture and the weather. I’d visited a few times but it wasn’t like living there, I couldn’t understand why I had to work for my own money and all those things and it became quite popular back then. We got popular that my mum would call me from Lagos to say they’re discussing a topic I’d written on my blog on radio. I didn’t feel comfortable anymore. I felt like I wanted to be comfortable talking about myself. I knew that I love to write but I wasn’t ready to talk about myself in that way, having people talk about my life on radio. So I decided to try my hands at fiction and I went through about 8 years of writing different things, short stories and even books that I sort of self- published and gave to my family. Things like that until the point where I felt that I needed to do a creative writing masters, maybe to validate the thought that I could write. It was an adult course. Everybody there was an adult, everybody there had jobs and were just trying to rediscover writing. That’s what led me to the Masters in Creative Writing which I thoroughly enjoyed.

KT: Do you think that was helpful in finally getting you to become an author?

AD: I think it gave me the discipline that I needed to write what I would call a standard piece of work and its funny because my book is not in Standard English. What I mean by that is that having the scrutiny of classmates who were fantastic writers, having them scrutinise and critique your work was invaluable. And to understand the theory of creative writing which I’d never looked at, assessing essays by great writers and dissecting short stories by some of the greatest writers, even Nigerian writers. Doing that in class opened my eyes in a way that nothing else had. I couldn’t understand why someone would call themselves a lecturer or Professor of Creative Writing until I did the course. That’s when I realised it’s not just about telling the story, sometimes the science behind it. I would say yes, it was very valuable for my own development as a writer. But in helping me to get published, I think for me it was really entering a competition, that was really what helped me. The thought of entering a competition came from my supervisors. One of them said ‘Abi, you should consider putting this in for a novel competition’ and I did and that was where the publishing came from.

KT: Were there any Nigerian writers that particularly influenced you in your writing process? Until recently, with Chimamanda, Sefi Atta, etc, it took a while for Nigerian female writers to get the kind of adulation that their male counterparts got. So, in your own process of becoming an author, which Nigerian writer or global writer’s style influenced you or influenced the way you wrote?

AD: I think in terms of inspiration and realising that I could do it, I’d have to say that Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me was great because it was contemporary, it wasn’t historical. Yes it dealt with politics but it was used as fuel to drive the story. I love how real it was and the characters were just themselves. I love that and I sort of saw us as peers, the same age group and I felt, ‘if she could do this…’ And she was shortlisted for so many awards. I felt, look I could tell my own story as well. I think in terms of style of The Girl with the Louding Voice especially, I was really swayed by Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy which he wrote many years ago and I found by accident. I think maybe 3 chapters into writing The Girl with the Louding Voice and I felt ‘there must be somebody that has done something like this before’ and I came across Ken Saro-Wiwa’s book. Even though his own was more of pidgin, sort of Delta lingo. But I just love how he was himself; he didn’t care about anything; he was just telling the story. He really inspired me. I think he gave me the belief that this book will be read by other people even though I wasn’t writing it for other people. I was writing it for my dissertation but I had a tiny hope that all writers do that, maybe it would go beyond the walls of the classroom.

KT: How long did it take you to write from the beginning to the end?

AD: Three years. It took 3 years. The first draft was me just pouring everything out. Adunni just doing whatever I wanted to do with her. Then it now got to the point where I knew that there was a competition I wanted to enter. I remember I was in Lagos when I got news that I had been longlisted for the competition and I had 4 days to shortlist. I was in my hotel room in Lagos, I didn’t sleep and I was just writing like a mad person then because I felt this is serious, somebody else is going to read this. After it was acquired, I think it went through another year of structural edits and going through the whole story, breaking it apart and bringing it together again

KT: Did you win the competition?

AD: I did.

KT: So, let’s go into the style, very unique style. When I was reading, I was thinking of Ken Saro-Wiwa myself, he is one of the few Nigerians writers who have tried to rebel in terms of style and use a certain type of English that is not usually expected or common in writing. How did you choose that particular style? How did you decide that this is how I want to write? We’ve had some writings before where the characters speak in substandard English or differently styled English but this is the first time since Saro-Wiwa that I’ve seen the narrative itself take on the style of that writing style so how did you choose that?

AD: I knew I wanted to tell a story about a girl who had been denied an education, about some of the things that some young girls are made to go through. I wanted to highlight these things; they really weighed on my heart especially as a mother of girls. But I also knew that many of the girls that I knew, even the maids my family had, many of them navigated the English language in their own way and they were perfectly understood. Yes, it might take a little bit of what are you trying to say? But yes, we understood them and we worked with them, so did many people that had maids back then. So when I got to writing the book, I wanted it to reflect this young girl who could not speak the English language but needed it to pass the message across but I was also trying to prove a point. I put it loosely, not like us being rebellious or anything. I remember my first job when I came to the UK, I was working in a jewellery store and I’m asked about a jewellery, a diamond and I would talk about it with a lot of exuberance and excitement because I enjoyed that job and it would always be ‘oh, you speak good English’ and I was like I don’t understand what that means. I wanted to prove that the fact that you speak good English does not mean you’re intelligent, it’s just a language and I think my character made that reference in the book. In the story, you find that immediately a lot of people hear Adunni speak, they tend to look down on her and assume that she isn’t wise. But on the contrary, she is the one that points out a lot of the mistakes that the characters in the story were making. I think it was twofold. One was to reflect what I had seen growing up with young girls in the pursuit of education and who were denied this but also to prove a point that you can actually understand people who don’t speak a certain way. English is just a language but it doesn’t mean you cannot get the essence of what they’re trying to say and I’ve been surprised and pleased by the reception of the book. First there was a lot of ‘what on earth is she trying to do her’ in the first few chapters. But by the third chapter, the brain sort of recalibrates and it clicks, you get what she says. It was a risk. I will be honest. I was doing it doing my Creative Writing course and I felt ‘what do I have to lose? We will see what comes out of it.’

KT: The first few sentences, you can say this is how I want the characters to sound but you have to sustain it for the whole novel, how did you get through that from beginning to the end and did you ever consider giving up and switching to Pidgin or something else?

AD: Yes I did, I did consider giving up a t some point. I said to myself that Adunni’s thought would probably be in Yorùbá and English. If we take the Yorùbá translation and we say, ‘orí n fọ́ mi’, it means ‘I have a headache’, right? When you want to write that in literal English as someone who is trying to learn the language, the person might say ‘orí n fọ́ mi, my head is breaking,’ you know. What I tried to do was to make it something that you could read. With a little bit of broken English and a little bit from my daughter who was 3 at that time and I find it fascinating. My daughter was born in England, went to Nigeria when she was 6 months old and at 2 years old, surrounded by English speaking people, still navigating the English language in her own way, you would see things like ‘tomorrow after tomorrow.’ There were so many things that she said that I borrowed. I find it fascinating that people actually learn languages in their own unique way and they try to make sense of the world with their own limited vocabulary however they can and I thought okay, Adunni speaks Yoruba, why not use that? There were parts where I used some Pidgin English but I didn’t want it to be directly Pidgin English. Anybody can speak Pidgin English, even the most educated person. I didn’t want it to be Pidgin English because I think it would just remove the essence of her character. It was just borrowing all sorts. I had a glossary at the start of the book for her commonly used words and phrases so I would not forget but it was a challenge and of course as the book carries on, her English improves just slightly. I wrote the whole thing in Adunni’s voice then I went back 5 chapters then I started to tweak one or two words to make it organic.

KT: One thing I noticed as a linguist and someone who pays attention to language acquisition is how it seems like the language was a kind of translation of her Yorùbá thoughts, the way we typically say things in Yorùbá, translating directly in English, transliteration into Language. Would you say it’s Yorùbá English then?

AD: Maybe we should say that actually. You’re the expert on this; I’ve always been saying non-standard English.

KT: You can say its Yorùbá English but there are also people who would push back and say that not every Yorùbá speaks like this. I think the best ways to say it is that it’s a kind of developmental English, the type you find from people who are trying to learn the language from a different background.

AD: Absolutely.

KT: I was reading it and I’m like ‘I’m going to catch this writer somewhere, is the language going to remain the same from beginning to the end and when I finished it, I went to the beginning to check how she used to speak in the beginning and I said we can make a case that she has improved, not completely because she hasn’t gone to school but she has improved. So thank you for that, it’s a very nice experimentation, very interesting. How have the responses been in Nigeria, in the UK and the US with people who speak English as a native language? Has there been any particular difference in how they access the way you use language?

AD: I am very grateful to be honest, for the reception. I remember the night before it was to be published, I could not sleep. I said ‘is it too late to change my mind because I don’t know what I’ve done here’. I was expecting a lot of backlash especially from Nigerians, because I’d won the Bath awards and I know that there were over 1700 entries all in standard English. I felt a little bit comfortable that the non Nigerians did not seem to have a lot of problems with it. In fact, they seem to really enjoy it; they thought it was quite fresh. It’s done quite well in the US and it’s picking up in the UK. When it came to Nigerians, I was quite worried; I’ve been on a lot of Zoom calls, book clubs. One of them, I was saying to my brother before I joined, ‘if they attack me, I will just hang up, I will just say that I have technical difficulties and I will disappear’ but it was very nice, we had a very engaging conversation. There were a few people like you who said to me ‘Abi I’m sorry I’m Yorùbá and even if I didn’t know how to speak, I would not speak like that’. I said that’s you and that’s why you have creative license, a suspension of a little bit of disbelief. You have to write something that can be read and digested. No writer writes how humans literally talk, you can’t write dialogue like that so you have to bring in your own creative manipulation into the writing so that it can be digested and read, otherwise you’ve failed as a writer. What really took the conversation with the Nigerians was about how we can do better with this housemaid situation and I enjoyed that. There was a little bit of, I wouldn’t agree on how you wrote it ; but we came to a general consensus that it was good because it brought out this problem.

KT: One of the things that made me think a little bit about the language you used was somebody who reviewed it, I think it was Chibundu Onuzor who made the case that because the girl is Yorùbá and her internal process is Yorùbá and she’s competent in that language, to make her speak in that way while we are trying to express what she’s thinking about betrays our description of people who don’t speak English as uneducated. It made me think a little bit because I understand why we might think that by making people speak in that way, English readers would understand that she doesn’t speak English but it doesn’t mean she doesn’t speak. She’s smart and she’s thinking in Yoruba so why can’t her Yoruba be coherent as well. Did you consider that aspect in any way or did it affect the way you wrote the novel?

AD: If I recall that line that Chibundu said, I think she said if the character is thinking in Yorùbá, something like why doesn’t she speak in Yorùbá and when other people speak English, why does she understand? I said if that’s the case then I would have written the book in Yoruba, it’s as simple as that, it really is. But the truth is that I think in Yoruba sometimes. I speak out in English what I’m thinking. Remember this is a girl that I made clear at the beginning that she thought learning how to speak English was the ultimate goal. She realises towards the end of the book that it doesn’t mean anything. Yes it helps you to stand as educated and it helps you to communicate quite well but when she compares herself to another housemaid who was educated and had a good life but made some decisions that affected her future. She realises that English is just a language and I think that was the whole of that. Maybe Chibundu missed that. I could have written the book in Yorùbá and just proved a point but she can’t speak English so she’s going to be speaking in Yorùbá but you would not be reading the book if I had done that.

KT: So okay, enough about style, let’s talk about the content of the plot itself which I really enjoyed, a lot of ups and downs, from one tragedy to another. What message were you trying to send to society with Adunni’s story and how do you think you’ve achieved that.

AD: It was a cry for the girl child, the cry of a mother. One of the things that hit me when I started to write the story was imagining my own daughter or myself having been born as a maid. No one chooses where to be born. I also say that I love my parents but I would have maybe chosen Jeff Bezos or Oprah because they have a lot of money. You find yourself in the family you find yourself in and Adunni is one of those people that find themselves in a family of extreme poverty. Extreme poverty doesn’t always translate to the diminishing of the girl child because there are some people that are poor but would give everything to educate their girl child. I’m not saying education alone is one of those things that make a girl child but education is one of those things that allow children, male and female, to be able to make rational decisions and be confident and do so many things. I was trying to prove that point. Adunni’s journey, the child marriage, the escaping, the child labour and some of the other things that happened to her and the other female characters was me just trying to that that there’s a lot to be done in terms of disparity in gender, in terms of how women and girls are treated. Adunni’s father chose to sell his daughter into marriage when he could have asked the sons to work harder or he could have gotten a job to educate her but he didn’t see the value because he felt that she would get married someday and his name would disappear and she’s not worth anything. I was reading recently about certain Igbo societies where they just made a law that girls can inherit their father’s property. This is 2020. It’s not a Nigerian problem, it’s a global problem. I spoke to people from Philippines India saying ‘Abi, this is our story, this is the story of girls from our society.’ It’s a story about a girl child.

KT: Something I’m also curious about is the role of women in this story. There’s the grandmother who saved her, a co wife who helped her at some point and there was a woman who she eventually had to live with and her own issues with her husband and patriarchy. On the one hand, there is the little child trying to get freedom but it’s also a commentary on many of those other women whose lives intertwine with her as well. How did you choose to define the different characters of women that we meet in this story and what kinds of relationships do you have with these characters as well?

AD: Growing up, I’ve been influenced by a lot of wonderful women but I’ve also seen women in situations that break my heart. In any society you find women who are victims of patriarchy and you also find strong women and you also find women who are a mix of the two like Big Madam who is strong, entrepreneurial, an economic powerhouse who is able to create a fantastic business for herself but suffers the consequence of being married to a man that drains her emotionally, physically and financially but is not able to do anything because of what society would say. I wanted Adunni to have a glimpse into the future and understand that getting an education does not mean that you’re there. That there’s still some battle that you need to fight individually within yourself, you need to make certain choices around your spouse, around who you call friends, everything as you see in the case of Tia who was educated, came from abroad but she still suffers these things and had to relate to Adunni on a certain level to be able to talk about these things. I think it was trying to show Adunni that regardless of women’s economic background or financial stability, they have unique challenges that are shared among them. African women, we have unique challenges. I found out from talking to my friends that even we that live in England, there are things we talk about and I think ‘I cannot believe this is happening in the UK but it happens’ So I think it was just me trying to explore these things.

KT: Speaking of Big madam, why do you think she protected the man so much? I kept wondering myself, she’s educated, she’s financially sufficient and all of that but she still suffers like you said, many of these indignities. And, of course, we have many people like that in our society. In your own perusal opinion, why do you think she endures this much indignity and refuses to take responsibility for it?

AD: I think it’s because of her fear of the failure of her marriage. And this is not a woman thing, interestingly. This is a Nigerian thing. For me as a Nigerian, this is what I’ve seen and I think it’s for other parts of the world as well. I think I was speaking to an older person and they were talking about hiring someone for a job, a high profile job and they said the only problem is that the man is not married. I said ‘and so?’ Apparently, to them he being not married means he cannot take care of his home so how can he take care of the massive business? Maybe there’s some argument for that but I fail to see it and I think if you flip it over to the women, it’s even worse because the woman is seen as the one that keeps the home together because you. We’re always advised that you have to work hard, make your husband happy and keep your home. I cannot count how many times I’ve seen so many commentaries on the woman being told to do these things. Big Madam makes a statement in the story where she says, ‘where will I start from?’ because she feels that some of her clients, if they hear that she separated, she feels that her clients will not patronise her anymore. She feels she would lose a lot if she walks out of that marriage. And she wants to protect that and remember she’s made her friends believe that she’s very happily married and her man loves and takes care of her and that’s very common. And so that would be a huge admission of failure on her part if she came out of that marriage and that’s why she tries to patch until she couldn’t anymore.

KT: How do we explain her own negative behaviour, the violence she metes out to the people that work with her, the lower class people she surrounds herself with?

AD: To be honest, I wish I had answers to that. There was a video I watched in December. The book was coming out in February in the US so the book was done and dusted, I couldn’t do anything about it anymore. One of the Nigerian blogs shared it on YouTube, A woman had broken the head of her housemaid with a pot and the head was actually split open and she was bleeding. The maid was 9 and they asked her why. She said something along the lines of maybe she’s lost or something that did not make sense. I thought, ‘why do people do certain things?’ I feel that for you to do something like this to another human being, they’re not sane, sorry, something has to be wrong with you somewhere. And that’s why I try to shoe in Big Madam. As a writer you do have to show some of the inner workings of her mind, her frustrations. And that’s why she tries to channel the frustrations she’s getting from her marriage into the helpless and that’s the only way I could try to explain it but I really can’t, because article after article that I came across, it was the same story. The woman beating up the maid for upsetting her, very similar stories of either stealing or her husband trying to sleep with her. I just did that with The Girl with the Louding Voice to show what I’d seen but I really don’t think there is enough to justify why another would treat someone who they feel is less than they are. We have that problem of class divide in Nigeria. I can’t tell you how many times I go to Nigeria and I’m very polite and I’m saying thank you so much to someone and somebody taps me and says don’t be too polite to him o, he will misbehave. What does that mean?

KT: Exactly, I think you illustrated that very well, the class divide, just people speaking to her at a party, just complimenting her makes her feel very special, are you talking to me? Are you apologizing? You see it a lot and it also affects how people behave and the dynamics of society. People patronizing child labor, being able to wipe that out of their heads without any kind of self-appraisal that they’re contemplating violence and oppression. There’s also the irony that she seems to be advocating buying Nigeria but, in the end, she ends up actually corrupting the environment.

AD: Absolutely

KT: I want to talk about the other characters that are not as central but are still relevant to the movement of the story. Khadija, for instance who we met at the beginning of the story. I have had people ask me why Khadija had to go the way she did and because she had left her own marriage, that have you considered the possibility that people might think we continue the idea that women get punished for indiscretion while men don’t get punished because obviously at the end didn’t suffer the same punishment.

AD: I’ve never heard that before and it’s so interesting you say that. Khadija made her choices because she was in search of a male child. It’s not her duty to search for a male child. But she felt like this is what she needs to do. It was me trying to say that this is one of the consequences of what we let women go through. She also refuses to go to the midwife because she doesn’t want a contamination of what she is expecting and she loses her life in the process. She suffers the severe consequences, that’s all I was trying to say. In fact, I read a blog I think 2 days or so after I’d written that scene and I was so shocked. The blogger asked the questions that how many of you have done certain things in search of a male child and the comments broke my heart. IVF after IVF for those that could afford it, one woman said that she has 5 girls and her husband who is very wealthy has told her that she must have a boy. The fact that Khadija did what she considers necessary to get a male child because that is what stands at stake between her own safety, feeding and her daughters versus anything else. I didn’t think of it that way at all but now that you said it, I would consider it again but it wasn’t that.

KT: At some point, I think I myself was expecting something to happen to Bamidele. I kept expecting to see his name back in the news sometimes towards the end of the story.

AD: You know if you think about it, men get away with a lot of things. It’s the reality, and sadly, that’s what happens. A man has had 5 girls and he marries another wife and many times, the first woman has to embrace it. Not all women do but especially a woman who is not strong enough economically to be able to stand on her own or one who believes that leaving her marriage would cause problems would have to. I think it’s just the reality.

KT: Fiction sometimes refers to society, men get away with so much crap and women suffer the consequences. Men don’t get anything to hold them to account. From the father who married her off, to Bamidele and the other men who come into her life, Big Daddy especially. I also wanted to ask about Rebecca. I don’t know if I knew what happened to her. We heard a couple of things but do we know for sure what the truth of her situation was.

AD: Even I don’t know. I think with Rebecca, I was just trying to reflect. When I was growing up, there was a maid that I was friends with. She was a maid to a neighbour; she was wonderful, always smiling, and always happy. I think I borrowed a bit of her always smiling nature in Adunni’s character. I went back to boarding school and when I came back home, I quickly went to this neighbour’s house and I was like where is she? They were like, she’s gone. To where? And they were like we don’t know, we don’t care. It struck me that she’s gone and they don’t care. You hear of so many stories of maids who would go home for Christmas and they never come back. Sometimes they never get home; some of them might be kidnapped, used for whatever it was. I think I was just trying to tell a story of the problem of not regulating this industry, not having a database. I know I’m thinking far ahead but it’s doable. Not having a database where we have a register of these girls, especially those who are 18 and above that choose this kind of job. Why can’t we regulate it? You can’t employ somebody in a sane society and the person disappears and you don’t care. People ask me is there going to be a sequel? I don’t know. My mum, a Professor of Taxation, has not read a single word of fiction in about 30 years. She’s written so many academic papers so the lockdown forced her to read the girl with a louding voice and she read it and she called me and said. She said I know you think you’ve finished but it’s not finished. My mother who is 70 told me the whole of what would happen in part 2. In part 2, Bamidele would turn up with severe consequences for him. If there’s a sequel, maybe we’ll find out what happens to Rebecca but right now, what really matters is to know that many of these girls disappear and no one really cares.

KT: It’s heartbreaking the amount of danger they’re exposed to, especially because their bosses have different ideas about how disposable their lives should be. They don’t have any right at all. Her husband is showing interest in the maid and the maid gets punished, not the husband. The maids always are at the end of the stick. Rebecca’s story illustrates that perfectly and it’s very heartbreaking, especially because it keeps happening in real life.

AD: If Rebecca was a child of a wealthy or middle class family that came to work, because I know some nannies who are graduates. There’s respect, I know these nannies’ parents. You hear people saying in Yorùbá ‘Tani ẹ́? Ta ló bí ẹ?’ It’s just like ‘who are you?’ That’s the kind of thing that Big Madam does. You see that with Kofi who is Ghanaian and is a qualified chef. Yes she still tries it with Kofi but she is a little bit careful and I think I see that a lot. You see how people treat accountant versus housemaids.

KT: with this your passion for the plight of the underdogs in our society, the girl child especially. Outside the novel, are you doing anything specifically or should we assume that the novel is your own way of contributing to the dialogue.

AD: I think that as a storyteller, I think I’ve given it all the muscle I can. I’ve told the story that my soul wanted to tell but what I’m doing is that I’m trying to support agencies that are doing great things. There are so many NGOs in Nigeria doing something around child labour, advocating for education. I came across Slum2School which gives out laptops to children born into poverty in slums and I’ve supported things like that. I think the only part I can play the biggest part is to tell stories that hopefully resonate with people but behind the scenes, there are other things I can do. Hopefully, everybody will do their parts and there can be a positive difference.

KT: Your readers will also internalise the issues that exist and find ways the readers can also participate in helping to change society as well. You’ve done your [art, we should also do ours.

AD: there’s something I want to say, I joined a Nigerian book club of fantastic women, about 70 of them and they’re based all over the world. One thing that they all said was ‘I know that I’m not treating my maid badly,’ for those who have maids. One of them said but as of today, I’m asking all of you on this call to do the same, look at your neighbours and your friends, see what they’re doing and call them out. A lot of people on the call said ‘we’ve been silent, we hear of how our neighbours are not treating their maids well’ Those are the things we can do. we can start changing the word from our own little corners before we do the big thing like making policies which we know that could be a long time coming.

KT: I wonder what it’s going be like if we’re going to translate this book into a world language, maybe French or German. What obstacle do you think we’re going to have?

AD: It’s interesting as I’m waiting to hear, it’s going to be translated to a few languages so far. There is going to be Italian, Brazilian, and Portuguese. So far, I’ve not had any queries from the editors I’m suspecting they’ve managed to figure out… maybe they’re planning the same thing; they’ll probably have to tell the story in a way that their market gets it without losing the essence of Adunni’s character. So far so good, fingers crossed.

KT: So your own career, what’s next for you? What should we expect? Any other books in line? What are you planning to do next now that you’ve become a global superstar?

AD: I think I’ll continue writing stories. That’s what I’ve always been. A storyteller. I’m exploring ideas, different things. I know that I’m very drawn to stories about human nature, our motivation for doing what we do, I love to write stories about women and how they stand and are seen in society so it will probably be something along those lines. After I wrote The Girl with the Louding Voice, I went through a period of grieving for the character and I couldn’t write a sensible word of English for a very long time which was interesting, especially in first person. Each time I tried, I found myself slipping back into Adunni and I was like ‘what kind of thing is this?’ It’s taken me a lot of reading novels; I think I’ve just come out of that spell.

KT: So Abi, have you managed to write anything else after that?

AD: I’m just exploring. Right now, I think I’m more comfortable with third person, that’s the only departure from Adunni. Anything first person, even emails because my day job, I work in Pharmaceutical technology. I remember when I was writing the book, I would type an email and I would be like ‘if I send this, my boss is going to send it to me and say, you need to go for classes.’ Because I was constantly in the Adunni zone. I think I have managed to get out of that now; it took a lot of reading of novels. Just like it took reading of novels to get into Adunni’s head.

KT: Other than Saro-Wiwa’s novel, were there other novels you read that helped you get into that character?

ABI DARE: So there was The Colour Purple by Alice Walker which I absolutely love although it was reading African American English but it was interesting to see how she could do that throughout the story, then there was The Help which is a bit about, I think it alternates between Standard English and Non Standard English for a character. I also read a lot of journals on language and the politics of it. I enjoy academic reading, I’m quite academic as well so I enjoy just exploring that and seeing what might come out of it.

KT: How did you move from MA in Creative Writing to Pharmaceutical technology?

AD: I came into the UK to study law and when I finished my first degree, I knew I didn’t want to be a lawyer because when I looked around me, I couldn’t find any successful Black lawyers, Nigerian lawyers. All of them just seem to be doing one thing or the other. I might not have known them but I didn’t see them that time, that’s many years ago. I asked what makes sense right now and IT was the boom thing, everyone was entering IT. I said let me do something that is not technology as such but would utilise my love for speaking and writing so I decided to go into project management so I did a Masters degree in International Project Management and after that, I found myself working technology, I worked for companies like HP, BT, virgin Atlantic and then I found myself working in Pearson which owns Penguin. And then from there, I found myself working in Pharmaceutical Publishing.

KT: I want you to talk about your mum who you mentioned a bit earlier. I know that she has some influence on your development as a writer and as a woman. So, if you want to say anything particularly about her and her own life influenced your own choice of life career and how the character you created also benefited from that experience.

AD: Thank you for that, my mum is wonderful and she was separated from my father from when I was quite a young girl and she raised my brother and I, she educated us and I know that she sacrificed a lot. Even as she was doing that, she never lost sight of her own goals and her own development as a woman. She worked in taxation and worked in the Federal Inland Revenue Service in Nigeria. She retired as the third in line to the chairman, coordinating director, first female coordinating director. After that, she went to the academic world and became the first female professor in taxation in Nigeria. She has written over 130 publications on taxation, she wrote the first Nigerian, potentially even African dictionary of tax, it took her 10 years to write that, I grew up knowing that a woman could be anything she wanted to be because of my mother, that the breakdown of a part of your life doesn’t necessarily mean it needs to break down your entire life. I remember vividly my head on her laps and a typewriter beside her and her typing books. She kept on writing, all academic books. I remember the conversations I had with her, she told me beauty is fleeting, it’s temporal. My mum would always say I’ve never met anyone who, at the age of 20 looks exactly the same at the age of 60. But I’ve met people who, if they invested in what is in their mind and became a better person, when you meet them at 20 and 80, there is a huge difference, because it adds more value to their lives. She has always been driving for me the importance of being a woman that can make a positive impact but also increase myself. She’s always said to me, your greatest investment is not in properties, cars, bags or shoes but it’s in yourself. I dedicated the book to her because I remember when I was about to do my Creative Writing masters, she said to me, you can do it. She said in 3 years time, you’ll have a degree. You know Nigerians like degrees at the back of names. She still said to me, why didn’t you add all your degrees? I said we don’t do that. You’ll have MA at the back of your name, go and do it. She’s such a great woman who is totally humbled and totally influenced me so much. And that’s why Adunni, at the start of the book, is suffering from the loss of her mother. I could write that because I couldn’t imagine what would have been my story if my mother had not taken up raising me, my brother and me and just investing so much in us.

KT: How any were you?

AD: 2

KT: We thank her, without her we wouldn’t have had this lovely novel that we have. It’s obvious from what you said about her and how you mentioned her in interviews that she had a substantial impact on your life and your creativity. We’re grateful for her, thank you. Is she in Nigeria?

AD: She’s in Nigeria.

KT: I was going to ask about movie adaptation, should we expect something like this?

AD: I don’t know. As a writer you only have control of your manuscript. For every writer, it would be a dream come true. We’re just waiting to see what happens, fingers crossed.

KT: Are you reading any interesting books right now?

AD: I’m reading Hamlet by Maggie O’Farrell.

KT: Not Shakespeare?

AD: It’s not Shakespeare but it’s based on Shakespeare’s son, I believe. I’ve just started it, the writing is brilliant. It’s written in 3rd person present tense and I’m just loving how she’s crafted words. It won the Women’s prize.

KT: Do you have any more comments?

AD: I just want to say thank you so much for this. You gave me a very wonderful time, just having this conversation

with you, it’s been great.

This interview is a part of a longer conversation had during Ake Festival.

Kola Tubosun is the chief editor of Olongo Africa and author of Igba Ewe .

Abi Dare is the author of The Girl with the Louding Voice, shortlisted for LNG 2021 Prize for Literature.