The Nigeria Prize 2022: Garlands for New Blood

If it wasn’t obvious enough that the leading poetic voices on the continent now belong to a new generation of writers bred in the jungles of the internet and raised in the angst of 21st-century dilemmas and preoccupations, the new NLNG prize shortlist has made it clearer. The three writers currently on the shortlist — Romeo Oríogun, Su’eddie Vershima Agema, and Saddiq Dzukogi — were born within the last forty years, and have emerged with a voice embodying the urgency of the moment.

But they’ve been there for all to see for a while, simmering under the surface through the annual Sillerman Poetry prizes to the African Poetry Book Fund chapbook boxsets by Chris Abani and Kwame Dawes. I saw it when I edited the NigeriansTalk Litmag from 2011 to 2015, and when I guest co-edited Aké Review in 2015, from causal and serious interactions with the work of Nigerian writers online in various forms, and from my time lately as the publisher of this new platform open to such regular display of brilliance and wonder. What has been clear, from the new poems published at OlongoAfrica and sister publications like Brittle Paper, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, and others, is the fire, the honesty, the rawness, and the delicate imperative through which the new writers interrogate living — the crazy hybrid mess of a world we inhabit, where old roles have faded behind new ones, even while the facades remain — without the inhibition that seemed to have kept the older generation in a serene comfort of more tempered vituperations.

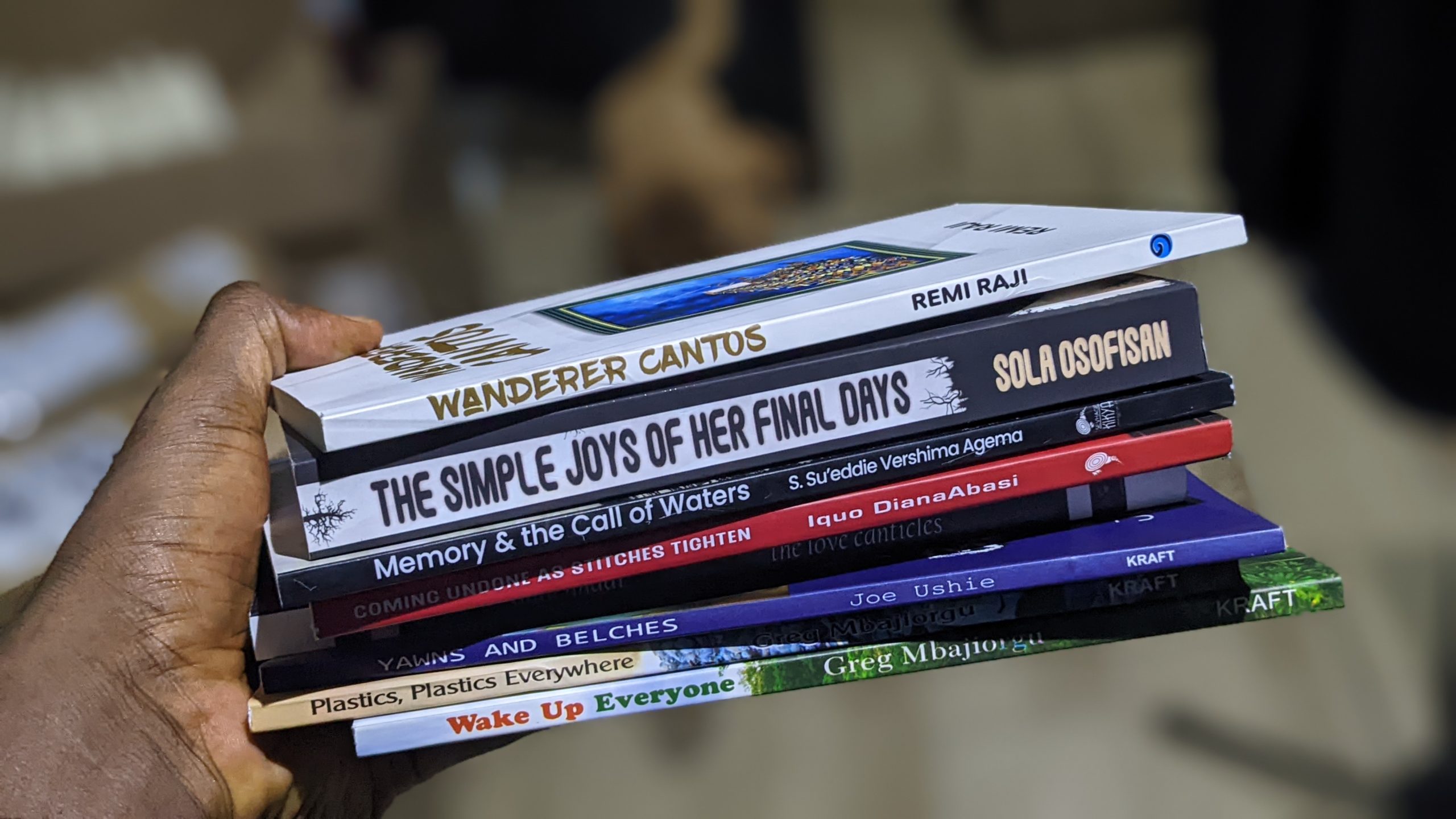

In this last assertion is a tension that was only just slightly unearthed in a conversation I had with the longlisted authors at Terra Kulture in early August, where the conversation turned on whether a delineation really exists — or was important to highlight — between the generation of Nigerian writers and their older contemporaries, or whether all the voices merely echo from one long stretch of inspiration blending into each other, and not constrained by age. Older writers, signified by Rẹ̀mí Rájí at the aforementioned event, would prefer that the conversation instead focuses on the themes and directions of the poets’ work, rather than their age or artificial grouping.

Thankfully, in selecting the winner of this year’s Nigeria Prize, which focused on poetry, the judges are afforded a bigger, wider, viewpoint. So are the readers and critics. Even coming to settle on these three writers already show that the criteria go beyond just the age of the writers. While one work is a personal record of loss and grief, one is a more wide view of our national and social predicaments, while another uses the personal to interrogate grand themes that cut across and even transcend national or generational boundaries.

Peter Akinlabí, in examining the power of Your Crib, My Qibla by Saddiq Dzukogi in his review of the same, remarked on its construction of “a most monogenic elegiac sequence…whose risk of monotony is circumscribed by the deft articulation of the profound candor of the poet’s feelings.” The work by Saddiq was inspired by the death of his daughter and is remarkable in its presence on the shortlist as one of the most intensely personal of the three. “This is a collection as beautiful as it is difficult”, Akinlabí says, because “it demonstrates the power of language to invent a corpus of extraordinary grace out of the chaotic currents of human sorrowfulness.” I found the subsequent conversation between the two writers significant as well, because of the space it affords them both to explore how grief can create both a profound hole in one’s heart, as well as a permanent record of beautiful myth-making memories.

The other work on the shortlist is Romeo Oríogun’s Nomad which I was privileged to read pre-publication, and blurb. It covers the poet’s journeys from Benin through Nigeria to parts of West Africa, and then the United States. In Romeo’s work, I have always found an authentic voice and a tenderness refined through the fire of travail and diligence of craft. The work hails from earlier projects of similar styles, in which travel and journeying become as integral to the work as a vehicle for personal stories. “Oríogun breathes art and has proved his mettle as one of the finest ambassadors for a generation of young, irreverent, convention-defying African poets,” Jerry Chiemeke says in his review of the book, with no word out of place. In our conversation with him later, he takes us on a journey through the physical and psychological milestones that have brought him to where he is today.

I spoke of Su’eddie Vershima Agema’s Memory and the Call of the Waters, as containing memories as “tenderness and sorrow…” like “a stream of calm waters waltzing through terrains of hurt and loss… personal as it is collective. The joke is on me that of the three books on the shortlist, it was the book I found most enjoyable. For all the dimensions of hurt and personal memorialization of chaos that it contains, it was also the only work that seemed to thrive, when it could, in the celebration of little joys and the nuances of existence. It must be why Unoma Azuah described it in her blurb as works which, “like songs, serenade the core of anguish and at the same time tease the ese of our most mellow moments.” In his own words when he spoke with Carl Terver, he sums it up beautifully thusly: “Yes, we should transcend the constant but it is okay to use the finite constant to navigate the infiniteness of the vastness that lies beyond our biggest imagination.”

Each of the three writers is well deserving of his place on the shortlist and brings new respect to the Prize and its judges. But recurring issues about the NLNG-sponsored Nigeria Prize for Literature have not gone away. The Prize still rotates among four genres every year, making it certain that the turn of the poetry genre will not come again in the next four years — a condition that may have occasioned the rush publication of hundreds of new collections this year so as to make the prize deadline. Carl Terver asked at the time, where the 287 poets who applied for this year’s prize came from so suddenly when their work had not been available anywhere else in the last four years. It is not a problem that will go away, and a Prize set up to encourage reading and publishing will do well to not wait for four-year increments to give a genre its due — especially since it doesn’t lack the funding to do differently.

The Prize still has not given due recognition to writings in any of Nigeria’s languages — a shame in my estimation. For a multilingual country with decades of history of publishing in native languages, the country’s biggest literary prize still focuses only on English, thus continuing the legacy of violence to local languages, which began in the seventies with the dearth of publishing opportunities for writers in Yorùbá, Igbo, Hausa, Berom, Esan, Efik, and many other languages after big Nigerian publishing houses became nationalized. Even in the absence of such a direct focus, translation is nowhere to be found as well, and all the books under consideration every year for the NLNG Nigeria Prize are written first in English. This needs to change. Or maybe we should just call it the Nigeria Prize for Literature in English.

And so we arrive near the moment where the panel of judges comes to its decision on the winner of this year’s prize. What would they be looking for? The validation of grief as a most appropriate monument to poetic expression (Dzukogi), or a deep exploration of the travails of exile by one man’s deft and deliberately provocative voice filled with tenderness, craft, and history (Oríogun) or an accessible work of varied memories, traversing a landscape of personal and collective journeys through joy and sorrows (Agema)? For me, there is already reassurance in the selection of these three books out of the previous eleven.

As true as it is that what unites them is less the age or “generational” grouping as much as the example of their creative fervour, there is still something to be said for an otherwise conservative prize committee daring the crowds to stick with these three fresh, vibrant, voices who already shine bright above the din; but who, like many prophets, have enjoyed garlands from elsewhere than in their immediate roots. Book prizes are already subjective as they come, but there’s something to be said for an award that justifies one’s faith in the honest diligence of that subjectivity.

___

The winner of the Nigeria Prize for Literature (Poetry) will be announced on October 14, 2022.

___

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún is a Nigerian linguist and writer, publisher of OlongoAfrica