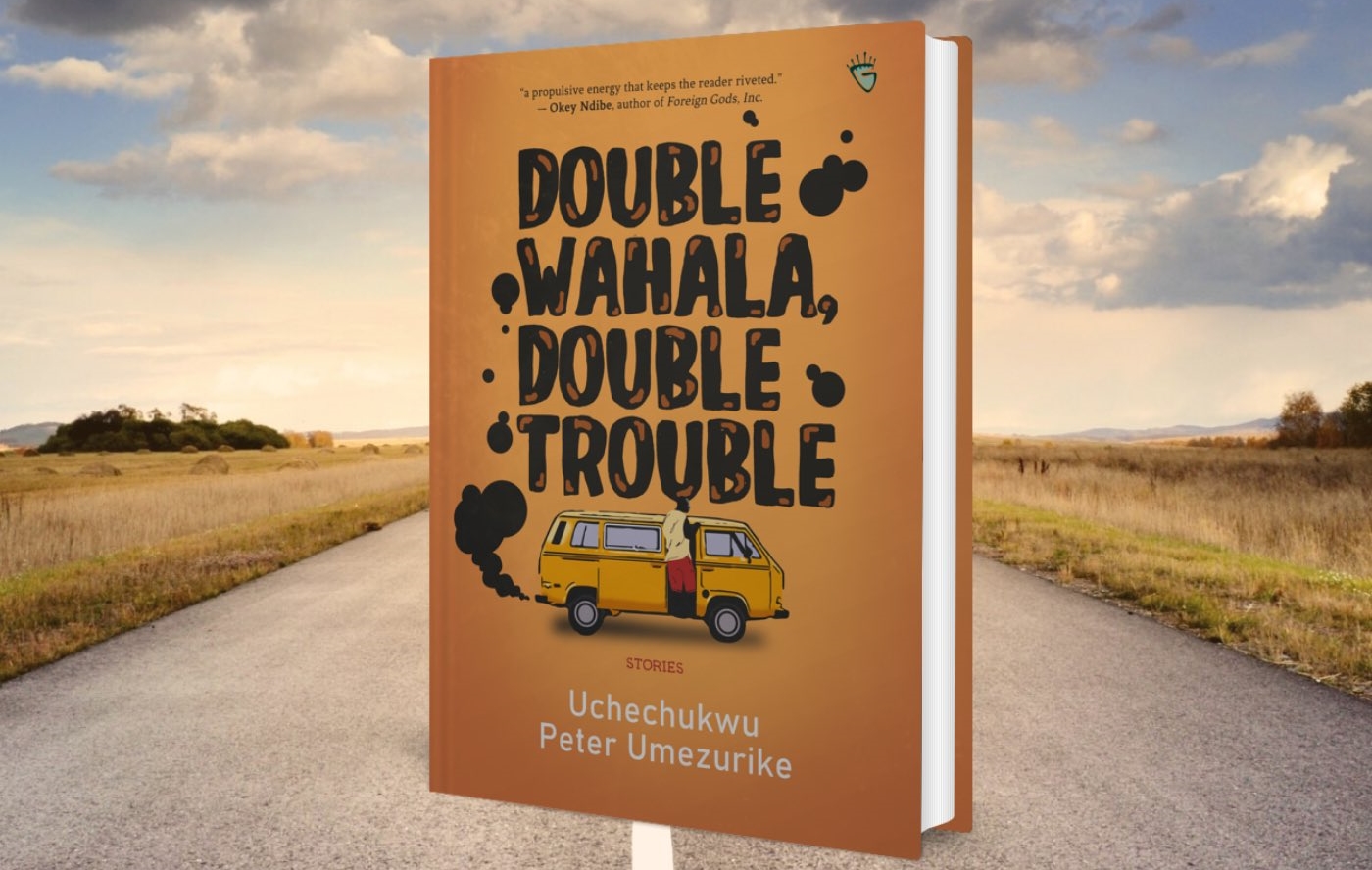

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike’s Double Wahala

In Nigerian popular culture, ‘double wahala’ is a Pidgin English phrase that was made popular by ace Afrobeat musician and activist, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. To repeat it by adding ‘double trouble,’ the English variant emphasizes the severity of the troubles. Nigerian literature has repeatedly featured the disorder and troubles that characterized postcolonial Nigerian life. Double Wahala, Double Trouble, the collection of short stories by Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike, contain 11 stories that represent Nigerian life in many of its iterations. The varied stories are held together by a vivid use of imagery and even in cases when the stories do not flow into one another, the ubiquity of trouble links them all together. These troubles manifest both on a collective and on a personal level across the country.

However, one of the stories is titled ‘Double Wahala’ and it details the life of two friends who are fraudsters and the tricks they play on unsuspecting members of the public. A lot of the stories are things that any Nigerian or follower of Nigerian news might have heard before. The troubles in the stories are best symbolized by the recurrence of violence and the casual way it seems to feature in the stories. This high propensity for violence is a recurrent theme in the Nigerian news cycle as some parts of the country are highly militarized. The stories are set in some parts of the oil rich Niger Delta and the Southeastern parts of the country, areas that currently experience a high rate of violence. The ethnic tensions that characters talk about also makes the stories relatable. This and other factors approximate to violence and violence recurs in the stories, morphing and manifesting differently in the experiences of the characters; from terrorism to communal agitations and all other forms of emotional violence. All these make the stories traumatic, and they reflect the psychological undertone of violence. Dreams and hallucinations are Umezurike’s literary motifs. In the story, ‘BAT’, a man’s wife and daughter are murdered in cold blood and he had to bury them without their heads. Sometimes, he is able to suppress this emotion, but it understandably influences some of his actions sometimes. His brother expects him to simply ‘get over the incident.’ (64) This hypermasculinity that is expected of men is a recurring trope in the stories. The male characters, both young and old are required to act in ways that dismiss their emotional needs and feelings. This masculinity increases the pressures that men feel and pushes them to both legal and illegal ventures. Young men are forced to risk their lives in defense of their homelands. Also, almost all the protagonists are young men who are pressured to make something of themselves by the family and societal responsibilities and the expectations on them. These conflicting ideas of hypermasculinity are overseen with masterful tact by the author, a research interest where the author has also developed academic expertise.

The author, Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a Nigerian academic, short story writer and children’s author based in Canada. He has published poetry and children’s literature and has been published both in Nigeria and outside Nigeria. Double Wahala, Double Trouble, in another sense also feels like a coming-of-age story for some of the characters. The characters in the stories are varied and this makes it difficult to put them in a box. The viable way of engaging the stories as a whole is to watch for tropes and resemblances in the characterization. When one of the characters tries to toughen up his son and his wife declares that they are not at war, he charges at her saying ‘Life is war. Living is war.’ (67) This is a feature of all the stories as they all live like they are at war, both actively and passively. From the struggling artist to the freedom fighter, all the characters have to fight for freedom and sanity in the midst of uncertainty and precarity. The Niger Delta villages featured in the stories have been highly militarized by the multinational oil companies and the youth groups fighting for compensation from oil pollution are fractured into groups, attacking one another and making the villages unlivable. In the end, no one wins.

The ghost of Biafra is one thing that looms over a lot of fiction from Nigeria, especially fiction authored by people from Nigeria’s Southeastern parts. The Nigerian civil war is so pervasive that sometimes, authors try to force it to be part of the plot even if it does not fit. This is understandable as many of the issues that led to the war remain unsolved in modern Nigeria. In the case of Double Wahala, Double Trouble, the Biafra war occurs intermittently, and it is intelligently woven into few parts of the plot. There are other issues that affect Nigeria that feature more in the plot as a trope: sick parents, freedom fighting, infidelity, tensions in marriages and other issues.

A simplistic reading of some of these tropes might suggest that they reinforce erroneous stereotypes that have been long perpetuated, but these stereotypes occur within the country. Some of the female characters are portrayed as being obsessed with churchgoing and spirituality almost to a point of illogicality. Some of the villagers are also cantankerous and they betray themselves. In an instance when a daughter gets pregnant, the father’s immediate reaction was to body shame her and declare ‘it seems you’ve only grown fat and foolish.’ (126) These stereotypes, as harmful as they are, reflect some of the daily experiences of many Nigerians. Even if they seem harmful, they are true. The author also deploys the Igbo and Pidgin English language to make the stories more relatable and engaging. Even for non-Igbo readers, the stories are understandable and the language use helps to situate them properly within their cultural milieu. The author also reworks a lot of idioms and his use of language is inventive. An example of this is seen in the line: ‘But it’s useless crying over broken eggs-or eggs that have already hatched.’ 125’

A balanced mixture of popular culture references and social commentary shocks the readers while at the same time being didactic. Some of the popular culture references are real and they make the stories timelier and more relatable. One of the stories in the collection, ‘RAIN’ ends with a comment that says ‘(in memory of Tekene, Chiadika, Toku and Ugonna October 5, 2012).’123. The names mentioned in the comments immediately reminds readers of the unfortunate lynching of four students of the University of Port Harcourt in 2012, a case now memorialized as the ALUU4. The story itself ends with an innocent man being lynched by a mob because he was mistaken for a thief. Even though the comment has one of the victims’ name as ‘Tekene’ instead of ‘Tekena’, the shock value of the story remains and the reader will be jolted by the reminder and attempt to memorialize the incident.

Uche Peter Umez, as the author is fondly called, is a decent teller of Nigerian stories. He engages memory comprehensively. Yet, his use of language is sometimes influenced by his status as a Nigerian in the Diaspora. The repeated use of ‘washroom’ instead of ‘toilet’ in a Nigerian story reek of his diasporic inflections. The stories also offer lessons in morals even if they tend towards being existential in nature, like the author emphasizes the intractability of life’s troubles.

Ayọ̀délé Ìbíyẹmí is a supporting editor at Olongo Africa. He is a reader who writes occasionally. He works at the intersection of literature, Life Writing, Popular Music, Tech, (Multi)Media, History and Art. For him, language is very important and words are what make the world livable.