The Strangers of Braamfontein’s Slightest Hope

Readers of Amma Darko’s Beyond the Horizon, Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters’ Street, and Ifeanyi Ajaegbo’s Sarah House may find Onyeka Nwelue’s The Strangers of Braamfontein familiar, especially in its discussion of sex trafficking of African women. However, that is where the comparison ends. There is blood in Nwelue’s latest novel—lots of blood. This is not a book for anyone who flinches fast, the timorous, for it brims with bloodlust and bloodshed. And there is more sex, more drug, more death than you will find in any of the mentioned novels. The book touches upon hope, too.

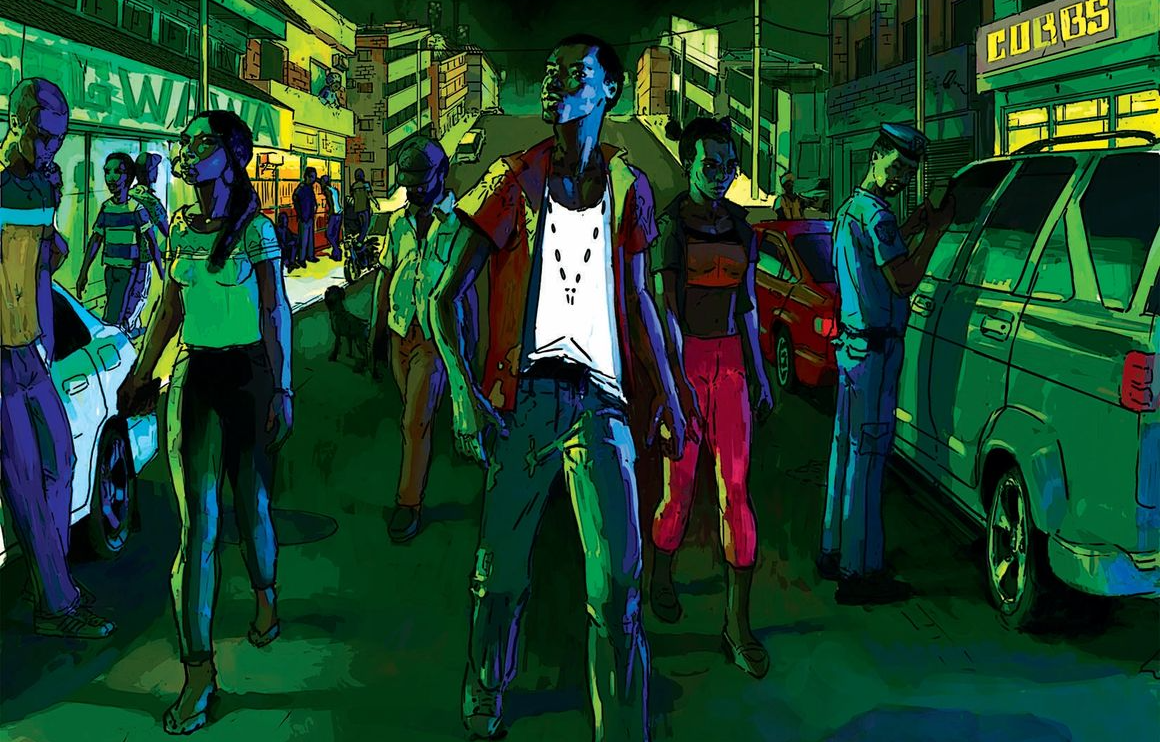

Yet hope is no more than a filament, a glimmer easily smothered, in post-Apartheid South Africa. That is what Nwelue tells us, quite blatantly, as he flawlessly captures the saying that those who live by the sword will die by the sword. The Strangers of Braamfontein strikes at the gut—lusty, raw, gory. Replete with instances of sex, drug, and murder, it depicts a horrific portrait of postcolonial Africa. For instance, the South Africa Nwelue uncovers is a thriving netherworld of crime and violence, overrun with cutthroat drug cartels and prostitution syndicates. His narrative has the visceral quality of such South African fiction as Alex la Guma’s A Walk in the Night and Niq Mhlongo’s Dog Eat Dog. Still, Nwelue pushes the visceral to a chilling edge. There are references to anti-Blackness, xenophobia, and homophobia in his novel; however, he dwells more on criminality and savagery, portraying the Rainbow Nation as a place of relentless crime and violence. A dangerous country. Throughout the novel, we see that there are many ways of dying or being killed by a rival or an opportunist. There is death by gunshot or poison. There is also death by the blow of a hammer or drowning.

The Strangers of Braamfontein is a page-turner. It is also noir in every stripe, for it parades a motley of characters who are doomed right from the start, including duplicitous lovers, ruthless minions, penurious citizens, and even corrupt police officers. It has strip bars and nightclubs, and gang clashes erupt like rashes in The City of Gold. Almost every character is morally decrepit, irredeemable. There is hardly a single honest man or woman in the story. The Strangers of Braamfontein is divided into four parts and composed of brisk, vivid chapters. Some chapters contain epigrammatic narratives such that they read like self-contained vignettes. The novel’s strength lies in this striking narrative structure and its cinematic appeal, which renders some of its passages evocative and immediate. This is not surprising, considering that Nwelue is also a filmmaker. In addition to its narrative structure, the diction is precise and sparse; it shuns thick exposition and cuts to the chase in a manner descriptive of pacy thrillers.

Nwelue’s The Strangers of Braamfontein fits the migration narrative that depicts the precarious experiences of migrants abroad. In African Migration Narratives, Cajetan Iheka and Jack Taylor consider how African writers and filmmakers engage the theme of migration. Iheka and Taylor advocate for an ethic of hospitality, urging us to be more hospitable to migrants. Nevertheless, the migrants in Nwelue’s novel do not leave the continent because they can choose to migrate to the south of Africa to pursue a seemingly better life there. Indeed, The Strangers of Braamfontein is an immigrant story, but a bloody one. It is not about immigrants crossing the North African desert or the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. Instead, it is about continental migrations featuring Nigerians, Congolese, Ethiopians, Togolese, Cameroonians, Malawians, Ghanaians, and Zimbabweans, who flee their hopeless countries “for the slightest glimmer of hope or the semblance of it.” Only that the land they arrive in is already besieged by predators and preys, and to survive there, everyone must be both a predator and prey. Nwelue seems to state that South Africa is just as perilous as the countries from which these immigrants have fled.

At the centre of The Strangers of Braamfontein is Osas, a young Nigerian, who arrives in Braamfontein, South Africa, and is hired by Papi, a ruthless Nigerian drug lord. Osas negotiates the tensions and conflicts underlying the criminal world, proving himself to be just as talented and brutal, especially in his dealings with his boss’s adversaries. Killing one’s rival is a way of staying alive. Mulling over the murders he is forced to commit, the Zimbabwean Chamai laments, “That this isn’t what he came to this country for.” In his book, Issues in African Literature, the literary critic Charles Nnolim describes some contemporary Nigerian fiction as “fleshy literature.” He labels writers in this category as “fleshy writers” because they are preoccupied with carnality and thus celebrate debauchery. There is a dearth of morality in their novels, and the country’s future is abysmal. For Nnolim, these writers project Nigeria as a nation adrift. Nwelue’s The Strangers of Braamfontein exemplifies such fleshy writing, delineating how much of Nelson Mandela’s dream of South Africa has miscarried since his passing away. His characters straddle the space between decadence and decrepitude, rejecting any affiliations with pan-Africanism. To them, it is the flesh, its exaltation, that matters.

How might we read Nwelue’s social vision? There is little doubt that he offers us a pessimistic vision of Africa, to begin with—an Africa, where there is no redemption but damnation. Perhaps, this is the stuff of Afro-pessimism. Black suffering. Black degradation. Black death. Might we consider him an Afro-pessimist then? Should we consider his image of Africa as tainted with despair? Nwelue indicts the political elites and their treachery, plundering of the commonwealth, and the consequent “hopelessness” that drive their citizens “into South Africa and its resident demons.” If there is any consolation in Nwelue’s novel, it is this: Osas is the only male protagonist, who barely manages to escape with his brutalized life the stranglehold of criminality. Onyeka Nwelue’s The Strangers of Braamfontein is timely and urgent, a necessary read, in view of recent happenings in South Africa. Moreover, it is a novel that African migration and diaspora scholars may find relevant in discussing intra-continental migration and its complexities—insofar as they have the appetite for its grisly servings.

Uche Peter Umezurike holds a PhD in English from the University of Alberta, Canada. An alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), Umezurike is a co-editor of Wreaths for Wayfarers, an anthology of poems. His books Wish Maker (a children’s book) and Double Wahala, Double Trouble (a short story collection) are forthcoming from Masobe Books, Nigeria and Griots Lounge Publishing, Canada, respectively, in fall 2021.