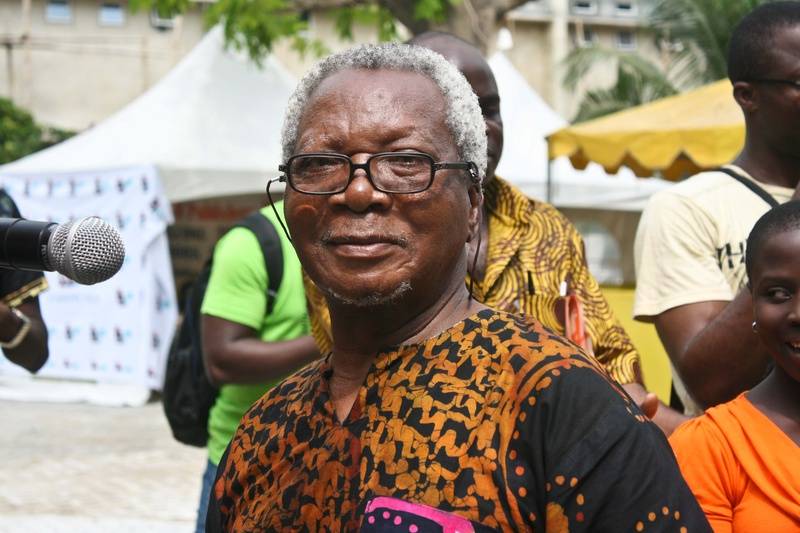

The Raft, the Rift and the Reconciliation – J.P. Clark among his Peers

One of the iconic photographs in Nigerian literature shows the poet John Pepper “J.P.” Clark Bekederemo – together with the novelist Chinua Achebe and the playwright Wole Soyinka – going to visit the military dictator Ibrahim Babangida sometime in 1986. Their mission was to plead for the life of Mamman Vatsa, a military General, who had been caught on the wrong side of a failed coup attempt. It was the first time Nigerians would be seeing their three great writers together in nearly two decades. For a nation to whom these writers represented an embodiment of their national pride in the twentieth century, it was a moment of relief. It was all well known that the boat of friendship of these writers was rocked in the circumstances of the civil war of the late sixties. That photograph has come to be associated with their reconciliation.

A picture, it is said, is worth a thousand words. Sometimes it provokes a million questions, too. Whose idea was this? Ṣóyínká was known to be the most politically engaged of the three. Was this his latest move? Could it be Achebe paying back a good turn? Vatsa, a vanity poet, had been a benefactor of ANA, the writer’s organisation of which Achebe had been founder a few years earlier. Clark, whose public engagement was not always well-known, had hardly registered in popular imagination as the initiator of that action. And yet, he was.

J.P. Clark is at once representative of, and a unique figure in his generation. Among the writers who helped usher in what is roughly called ‘modern African literature’ in the middle of the last century, he was also an oft-understated participant – misunderstood even, depending on whom you asked – in the interventions of that generation of Nigerian writers in the troublesome politics of the early years of independence. His life’s trajectory began as a leading raft in the flotilla of writers that explored the continent’s modern literature, charting its main course and putting down its key markers. The political turbulence of the early post-independent years caused a rift, and Clark would famously find himself adrift in an outlet separate from many of his friends. The involvement of writers in the Nigerian crisis would provide for rich debate in African literature for some time afterwards. In such circumstances, Clark, proud and famously taciturn, would seek justification for his position in poems and occasional interviews. The story behind the 1986 photo, as we would learn over the next couple of decades, was the beginning of a process of reconciliation that came to characterise the poet’s life in those years – his “days of grace”, as an obituary noted.

The Raft

If we overlook, for a moment, the marginalisation of the women of that first generation of Nigerian writers in the popular imagination of the era, the famous ‘quartet’ that Clark formed with the other leading men – Chris Okigbo, Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka – would become the storied careers of their time. They were a registered presence in the epoch-making Makereke writers’ conference of 1962. Achebe attended, already a minor celebrity with a breakout novel under his belt (Ngugi wa Thiongo had brought the manuscript of his first novel to show him). Soyinka and Okigbo caused quite a stir with some controversial statements (Soyinka, the negritude quip; Okigbo on the intended audience of his poetry).

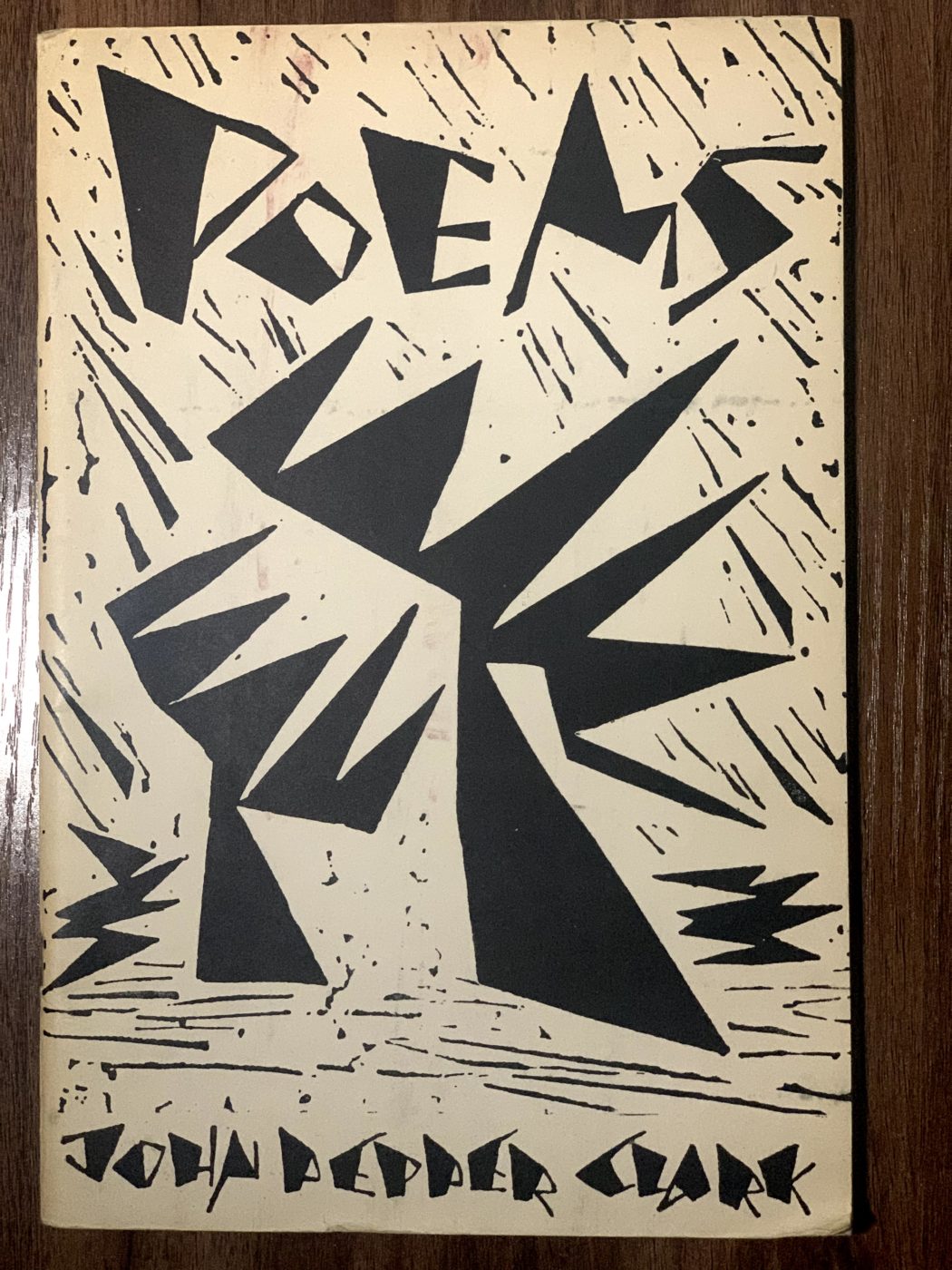

While there were no notable reports about Clark’s activities, or antics, in Makerere, back home, he was pivotal to those initiatives that were shaping the continent’s literature. Entering the university college in Ibadan after the other three, he became pioneer editor of The Horn, the student literary magazine. Okigbo, the only one among the other three whom he met in college, published his earliest poems in the magazine. Soyinka similarly published in the magazine on returning from Leeds university. Clark would also become active in Mbari, the city’s artistic club, later emerging editor of the associated literary magazine Black Orpheus. His play, Song of a Goat, was the first title under the Mbari publishing imprint. The imprint became the first initiative to publish modern African writers on a cross-continental basis. It opened up opportunities for other writers from across Anglo-phone Africa, including from Nigeria (Soyinka and Okigbo), South Africa (Dennis Brutus and Alex La Guma), Gambia (Lenrie Peters) and Ghana (Kofi Awoonor). If the account of the British publisher James Currey is anything to go by, a horse race of sorts was triggered when foreign publishing houses began to obtain international rights for the Mbari books. In a sense, it could be said that the notable winner of that race was Heinemann whose paperback ‘African Writers Series’ went on to become the unofficial home for emerging African literature for decades afterwards.

Indeed, it was the nascent stage of a cultural renaissance going on in Africa at the time and Clark’s role in it was notable (the first book-length history of Mbari – Robert Wrens’s Those Magical Years – The Making of Nigerian Literature in Ibadan – has been much criticised for over-centralising Clark). Mbari has only completed an arc that – together with the university, the country’s first, and the local television, the continent’s first – gave Ibadan the sense of being the centre of that renaissance in the 1960s. His early plays like The Raft and Song of a Goat, were first performed in the club’s theatre. Visual artists from the ‘Zaria rebellion’ – Demas Nwoko, Uche Okeke and Bruce Onobrakpeya – provided production design and illustrations for plays and publications. Other artists from across Africa, including the Sudanese dissident Ibrahim El-Salahi, visited and exhibited in its gallery. Fela Kuti’s first stint as a bandleader was in Mbari clubhouse. The beleaguered voices of South African poets like Brutus and Arthur Nortje first found a major outlet in its publications. Another South African, Ezekiel Mphahlele, while an exile in Nigeria between 1957 and 1961, was a founding figure in Mbari and had chaired its activities at inception. Mphalele would later go on to establish a similar club in East Africa as well as co-organise the famed Makerere conference.

Besides his role as a major functionary of these founding institutions, Clark’s artistic contribution to African literature is very significant. The lyricism of his poetry, coupled with the pervasive imagery of the Niger Delta wetlands – the latter only rivalled by the poetry of another ethnic Izon, Gabriel Okara – was a unique contribution to the writing of their time. In one popular poem, ‘Streamside Exchange’, he uses the locale to muse on the nature of mortality and loss:

Child:

River bird, river bird.

Sitting all day long

On hook over grass,

Sing to me a song

Of all that pass

And say,

Will mother come back today?

Bird:

You cannot know

And should not bother;

Tide and market come and go

And so shall your mother.

Similarly, Clark’s plays explore universal themes through the lens of the setting of the delta (The Raft), often mining the folklore and mythology of his Izon ethnicity (Song of a Goat, The Masquerade, Ozidi Saga). Soyinka directed and starred in some of these early plays on the Mbari stages. One imagines the experience rubbed off on him, considering the setting of his own play, The Swamp Dwellers. We therefore have Clark to thank for butting through and diversifying what would have ended up as a bipolar mind-grab in modern Nigerian literature: limited, to put it simplistically, to wisecracks in forested Igbo villages and felicities of Yoruba royal courts.

Of course, we say ‘simplistically’, since the writers of the time, as already noted in the example of Soyinka stated above, did reflect the cosmopolitanism of their education and experiences in their works. In the case of Clark, his verses cross over the entire terrain, including pastoral culture of the savannah (‘Fulani cattle’) and Yoruba mythology (‘Abiku’). An example of that cosmopolitan cross-current could be found in his poem ‘The Imprisonment of Obatala’, devoted to the Yoruba god of the title, but actually inspired by the batic work of the Austrian artist Susanne Wenger, and which title would later be adopted by the German Ulli Bier for his play written under the nom de plume Obotunde Ijimere. And of course, who would forget that famous homage to Africa’s largest pre-colonial urban sprawl (‘Ibadan’)?:

Ibadan

running splash of rust

and gold – flung and scattered

among seven hills like broken

china in the sun.

The Rift

There are reasons to assume, at first, that Clark’s public life and professional career was somewhat anodyne, even unremarkable, compared to his contemporaries. While Soyinka and Achebe had chequered academic careers, both resigning prematurely from the universities in Ife and Nsukka, Clark went on to a quiet retirement in the Lagos university in 1980. In the redefining National event of their lives, the civil war of 1967-1970, Clark appeared to have emerged largely unscathed. On the other hand, by the end of that war, Okigbo had died as a combatant on the Biafran side. Soyinka spent much of the war in solitary confinement following his return from a controversial voyage across the lines, aimed – depending on whom you ask – at seeking peace or coordinating with the rebels. Achebe emerged a much-scarred ideologue and propagandist of the failed secession bid. Clark, for his part, kept his job in Lagos while, for some time during the war, travelling the world on an international speaking fellowship that remained controversial for some time afterwards.

This, to say the least, did not endear him to his peers. Clark recounted to his official biographer, Femi Osofisan, an incident in London in which Achebe, then a travelling envoy for Biafra, met with Clark in the home of their publisher and declined taking Clark’s offer of a handshake. Something even more dramatic happened between Clark and Soyinka, then newly returning from prison, in the London home of another publisher when it was revealed that Soyinka was about to include some allegations in his about-to-be-published memoir about Clark’s travelling activities during the war.

And yet, like many of his contemporaries, Clark had not had a completely uninvolved role in the political events leading to the war. Besides being the epicentre of a renaissance, as we had noted before, Ibadan of the 1960s was also the capital of the Western Region, which was a hotbed of political discontent in what is now called Nigeria’s first republic. The circles of younger actors in both phenomena very much intersected. Clark, like Okigbo, was a friend of Emmanuel Ifeajuna, the ideological leader of the group of ‘five majors’ that carried out the coup d’état which terminated that republic in January 1966. Ifeajuna was an Ibadan graduate whose radical, if capricious politics went back to their school days. Evidence from the papers of the novelist and anti-Apartheid organiser Manu Herbstein also suggests that Ifeajuna might have been involved in the underground leftist movement before being commissioned into the Nigerian army in 1961. At the time, he was a teacher in Abeokuta, less than 70 kilometres from Ibadan. Okigbo was, at different times, save for a brief period when he worked as librarian in the university in Nsukka, Eastern region, a teacher in Fiditi, a village in the Ibadan fringes, or as a publishing manager within the city. Clark, meanwhile, had worked at different times in the city as either civil servant or university researcher, before taking up a job in the Lagos university. In any case, like Achebe whose broadcasting posting had brought him to near-by Lagos from Enugu, Eastern Region, in 1960, the activities of Mbari always brought them to Ibadan.

As evidenced in their writing, these writers were certainly drawn in by the political events of the time, including the turbulence in the Western Region (as reflected in the later poems of Okigbo) and the general environment of corruption which the politicians were beginning to create (as reflected in Achebe’s last pre-war novel). Soyinka might have taken it up a notch when he was accused of, but unsuccessfully prosecuted for armed robbery after he allegedly held up a radio station at gunpoint and replaced an official government broadcast with a pre-recorded tirade.

Clark’s specific political involvement at this time, again, is not well publicised. In fact, he was the one Soyinka first called to facilitate his bail after the radio hold-up fiasco. Following the failure of the coup-plotters to replace the government they overthrew and Ifeajuna’s escape to Ghana, it was Clark and Okigbo that were requested to go and persuade him to return home and face the consequences of his actions. On their return flight home with ‘King Fred’ (Ifeajuna’s passing name on the flight) it was Clark that Ifeajuna entrusted with his hurriedly written manuscript documenting the coup. In his poem, ‘Return home’ from the war collection Casualties, Clark recounts the tense moment at the custom point:

And I alone on the tarmac

With odd items to clear,

A number of papers I did not dare declare.

Nothing would come of Clark’s efforts to persuade both local and foreign publishers to publish that manuscript until its ‘official’ disappearance.

When we consider these pre-war activities therefore, it could have been merely happenstance that the ensuing civil war found Clark on the opposing side of many of his intellectual peers. The question whether he went beyond the call of bare patriotism – as would be understandable for a Nigerian under the circumstance – to actively engage in official efforts to neuter his beleaguered colleagues is an overcast on the legacy of Clark that he would fight for a long time afterwards. His collection of poems, Casualties (1970) documents his early post-war position. Its philosophical musing over the nature of war, and its wasting effect on all concerned alike, has universal appeal. This is nothing harsh or accusing like Soyinka’s war memoir The Man Died, or graphic in its grim details, like other poetry collections on the war, such as Achebe’s (Beware, Soul Brother) or Soyinka’s (A Shuttle in the Crypt). The following is an excerpt from its famous title poem:

The casualties are not only those who are dead;

They are well out of it.

The casualties are not only those who are wounded,

Though they await burial by instalment.

The casualties are not only those who have lost

Persons or property, hard as it is

To grope for a touch that some

May not know is not there.

The casualties are not only those led away by night;

The cell is a cruel place. Sometimes a haven,

Nowhere as absolute as the grave.

The casualties are not only those who started

A fire and now cannot put it out. Thousands

Are burning that had no say in the matter.

The casualties are many, and a good number well

Outside the scenes of ravages and wreck;

They are the emissaries of rift,

So smug in a smoke-room they haunt abroad,

They do not see the funeral pile

At home eating up the forest.

This poem became one of the most anthologised in African poetry. Many school children could recite its lines by heart. The competent lines, making little by way of specific moral judgement, were in tandem with the official attitude to memorialising the war. The government’s policy was that of no victor, no vanquished. That slogan might as well have been: ‘neither innocent nor guilty’. No medals were awarded for gallantry during the war, nor were rumoured cases of atrocities investigated and punished.

It goes without saying that Clark’s musing did not impress his peers who had been caught on the ‘wrong’ side of the war. It is understandable if they took personally his oblique references to smug “emissaries of rift” or prisoners “led away by night” who nonetheless should not make much of it. Regardless of the ultimate defeat of the Biafran side, writers who took the opposite camp against the Nigerian government had a sense of moral vindication which came from the condemnable atrocities and human suffering of the war.

The poem could also be considered a submission of some sort, in the academic conversations going on among African writers of the time. What is the role of the artist in the crisis of the sort which had drawn in and nearly consumed the cream of Nigerian writers? For some of the disputants, all that had happened was a political crisis into which no writer should have allowed themselves to be drawn. Ali Mazrui, in his polemical novel, The Trial of Christopher Okigbo, makes the most elaborate case for the politically disinterested artist. As he posited, “no great artist has a right to carry patriotism to the extent of destroying his creative potential”. Clark’s hardened position is reflected in the following statement contained in an interview granted for a publication by the American scholar Bernth Linfors a few months after the war (but published two years later):

I’m not impressed with the social or political life a poet lives outside his profession if he doesn’t produce poems. He is a poet because he composes poetry; he is a playwright because he writes plays, not because he is killing or getting himself killed.

Suffice to say Achebe did not agree with this neutral role of the artist. His rebuttal of Mazrui, put forward in his memoir There was a Country, relies on the postulation that African art is inherently socially inclined. Specifically, he had dismissed Clark’s collection at the time of its publication as, in essence, an impossible attempt to make a lie into good literature, while bewailing what happened to the Clark of ‘Night Rain’.

Soyinka, for his part, took a more universalist tack. In ‘Gulliver’, a poem from the prison collection, he indeed accepted the notion – implied in Mazrui’s “great artist” connotation – of the artist as a giant in his society. But this was not so the artist could assume a saintly distance in a moral dispute or fail to side with the truth. In ‘Joseph’, another poem in that collection, he states the position thus:

… A time of evil cries

Renunciation of saintly vision

Summon instant hands of truth to tear

All painted masks, that poison stains thereon

May join and trace the hidden undertows

In sewers of intrigue.

And just to be sure, since his own position should never have been confused as one informed by blind Biafran loyalty, in a poem co-dedicated to Victor Banjo (a Yorùbá like himself who fought on the side of the Biafrans), he said the following as though speaking for himself too:

They said to him be still

While winds of terror tear out shutter

Of his neighbour’s home.

In a poem written for Achebe at 70, Soyinka would vindicate Okigbo’s choice specifically, and underscore the duty of the survivors to defend his memory:

Absences surround your presence – he

The great town crier, Okigbo, and other griots

Silenced in infancy. The xylophone of justice

Chime much louder than the flutes of poets,

Their sirens lure the bravest to their doom.

But some survive, and survival breeds, it seems,

Unending debts…

(‘Elegy for a Nation’).

Soyinka went ahead to publish his ‘offending’ memoir. Clark took legal action, as he had promised in London, seeking reprieve from the allegations contained in the memoir. But this merely dragged on for many years and ended up unresolved.

Meanwhile, it did not help that Clark had not cultivated the kind of loyal following that Achebe and Soyinka had amongst younger writers, no thanks to his well-known aloofness. Biodun Jeyifo, the critic, was to famously call him the ‘Balógun Ọ̀tọ̀lórìn’ – the lone-ranger General – of African literature. These younger writers naturally sided against him in the controversy, as Osofisan would let slip in his biography of Clark. In 1980, Clark had to force the publisher Longmans to pull from the shelves – on the pain of litigation – copies of the first impression of The Poet Lied, a collection of poems by Odia Ofeimun. The book’s title, it hardly requires explaining, is a not-too-veiled play on the title of Soyinka’s memoir. Both Achebe and Soyinka were Ofeimun’s benefactors. Achebe had published Ofeimun in the magazine Okike while Soyinka included him, while still a student, in the cannon-making Poems of Black Africa. There is also the possibility, as this writer has noted elsewhere, that Niyi Osundare’s poem ‘A Dialogue of the Drums’ in his second collection Village Voices was a more oblique lob in the controversy.

The Reconciliation

In the last one and half a decade of his life, Clark had collaborated with two biographers on the subject of his life. That period also roughly approximates what, in a quick-draft obituary, Jeyifo has called Clark’s “days of grace” as said earlier. That was a period, according to Jeyifo, when his own generation of Nigerian writers, themselves now going on their sixties, began to note and enjoy a more welcoming, often generous, disposition from Clark.

One of those collaborations did not go well. Half-way through the research visits, Clark had thrown out the maverick Scottish-Nigerian writer Adewale Maja-Pearce from his country home on the bank of the Kiagbodo river. This followed a dispute over the nagging questions of the would-be biographer on certain information collected from the old poet’s papers. Maja-Pearce went ahead anyway, and published the hostile book – or “critical biography” – A Peculiar Tragedy” J.P. Clark Bekederemo and the Beginning of Modern Nigerian Literature in English (no doubt a titular pun on Clark’s lecture for his Nigerian Academy of Letters fellowship ‘A peculiar faculty’).

The circumstances of its writing and publishing did not leave Maja-Pearce’s book useless, although it came down with scathing receptions among literary enthusiasts. Admittedly, the plot, if there was any, can often be distracted. Besides exciting details about the circumstances of his fall-out with Clark, a large chunk of the book is devoted to re-litigating, with Clark as the scapegoat this time, old criticisms against the Mbari generation and their successors in Nigerian literature. In his book published in the early 1990s, A Mask Dancing: Nigerian Novelists in the Eighties, Maja-Pearce had taken issues with what he considered the narrowness of range in subject and language in Nigerian literature up to the 1980s. These flaws, he considers the legacy of the Mbari generation. Even then, the hastiness of his generalisation was not lost on his critics at the time. Ofeimun, in a lively exchange he had with the author on the pages of the defunct West Africa magazine, had called Maja-Pearce’s work “a hit-and-run”.

That Maja-Pearce resurrects these charges in a biography of this Mbari leading light and the circumstances of their discord might be indication that he took his work seriously and, having enjoyed Clark’s generosity with food, drink and board, did not wish to be considered a pen for hire. Besides, he seemed set on fulfilling his proposal that the work be a “critical biography” of the subject. In that regard, he perhaps wanted his to be the last word. That last word – the summation of the book – is that Clark’s position during the civil war has placed him in a “moral jeopardy” which has since affected the quality of his literary output.

In spite of its vastly different style, the favoured, official biography, Osofisan’s J.P. Clark: A Voyage, has a significant thing in common with Maja-Pearce’s work. Both authors adopt a ‘new journalism’ approach in which the process of researching and writing the books, the very interaction with Clark and his generosity – the “grace” – becomes the story itself. And this offers a pinhole into the body language of the subject and what would come across as his anxiety about the outcome of the story. The last two chapters of Osofisan’s book are dedicated to examining the great rift between Clark and his colleagues. Proceeding in a less inquisitorial manner, Osofisan’s overall intent appears to be that of fostering reconciliation. For example, taking a look at a tome of papers which could have illuminated aspects of the rift, he says:

I decided not to bother. What does it matter anymore, this story of four decades ago?

Time has passed and washed over many things.(p. 206).

Well, it does look like, as the biographer believed that time could degrade hard facts, he also believed that it could soften hardened positions and uncover hidden emotions. Besides, he might have been sensitive to the intent of the subject, in the way Maja-Pearce was not. It is equally not unimportant that Clark was to Osofisan’s career what Achebe and Soyinka had been to Ofeimun’s, having published a work by Osofisan, then newly out of high school, in the authoritative Black Orpheus. Whatever might have been the case, Osofisan sought closure, not through a hard probe into the papers, but through a hearty one-on-one with the old poet.

On page 207 of Osofisan’s book, Clark, in essence, betrays the most emotion to be known to the public and expresses the kind of understanding and empathy on the experience of his friends that were missing in the intellectual brickbats of the 1970s. In his interaction with the biographer, he confesses:

I told my wife, I can’t take it. What my friends have gone through… Chris dead, Wole in prison, Chinua running from pillar to post… Nature has been kind to me… compared to friends, my immediate contemporaries, I’ve had a charmed life.

“Maybe I didn’t go for the thing they went for. I couldn’t court death the way Chris courted death. I couldn’t face prison life like Wole went through. Prison is a terrible place. Wole could easily have been shot by the federal side! And I couldn’t run, couldn’t be a refugee like Chinua was, and now in his physical condition, living in a wheelchair….

For anybody looking beyond symbolism for a more substantive arc of development, Clark’s one-page ruminations in Osofisan’s book was the real public moment. And not to leave us guessing, in the penultimate paragraph of that page, Clark admitted that he was, in essence, pining for reconciliation when he mobilised his friends for that intervention on behalf of Vatsa in 1986. It was in the spirit of Mbari, one could imagine, in which politics interjected itself into literature. Perhaps Clark had asked himself: what would we have done in those magical years? Like much of the political dalliance of their youth, the 1986 mission failed. Vatsa, in spite of Babangida’s blasé assurances to the writers, was executed a few hours after they left the state house. But in warming the heart of the nation, Clark had, this time, won the symbolic victory alongside his friends.

J. P. Clark Bekederemo, probably born a year or two before the year 1935 more commonly stated in his bios, died in the second week of October 2020. He was buried quietly, by his instructions, “in three days/ Excluding blood and waste” (‘Of Sleep and Old Age’). In that week, a new generation of Nigerians, embarking on the ‘#EndSARS’ protest, made yet another attempt at intervening in the public affairs of their country. A side debate in the social media hubbub attending the latest protests was on whether any generation before the protesters’ ever tried at all. There is a lesson to be learnt in the lives and the struggles of Clark and his generation, struggles which have yielded personal trophies now and then, but flailed against more stubborn forces which still hold the levers of power and hold back the progress of the nation along with it.

Tides and markets come and go… and so is a generation.

——————————————

Deji Toye is a Lagos-based lawyer, writer, and cultural advocate. He can be found on Twitter @dejitoye.