The Life of a Poet

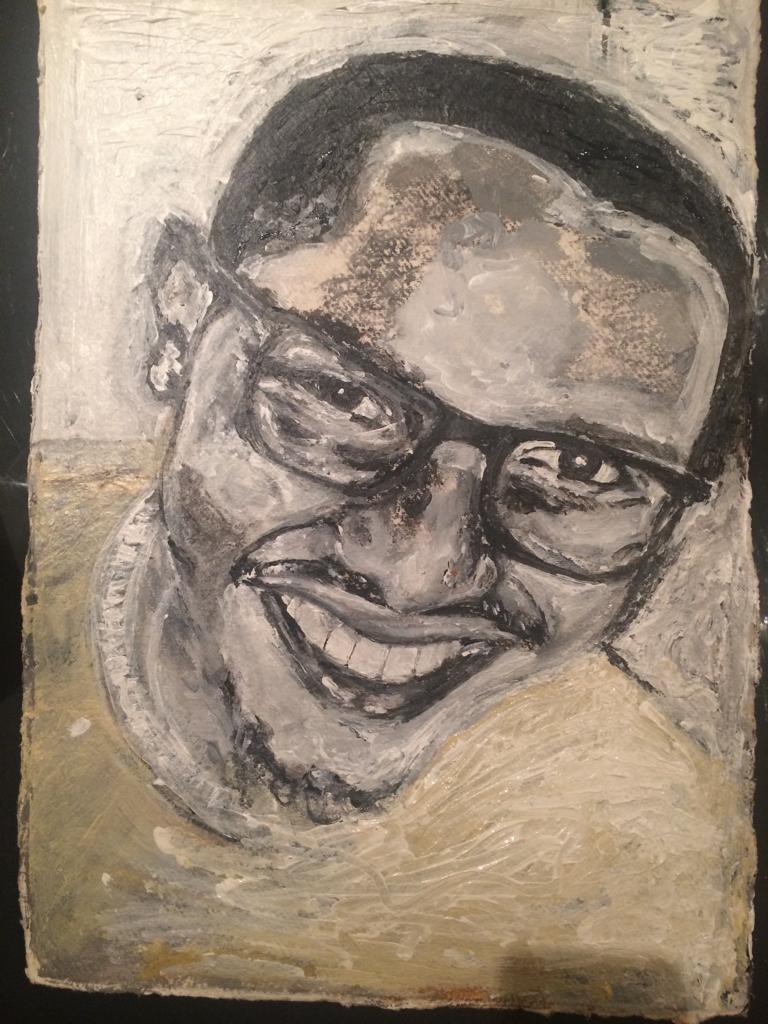

In 2011, Dami Ajayi successfully completed his first collection of poems, Clinical Blues, and it marked for him, the completion of an epiphany which began in 2007, when as a young medical student, a new vision of the world caught up with him. This new vision afforded him the clarity to see the world afresh from the humane gaze of how medicine related to the society, and this began an epiphany for him. It was this new found vision that handed Ajayi a torch with which to unveil muse for a turning point in his poetry. The title of the debut collection of poems was an allusion to this body of work which began when the world began to sing a new song to a poet from the four walls of the hospital. The collection established Ajayi’s place in the literary canon as an essential lyricist, who tried to aspire to the tall height of his influences.

The fifteen years since the journey of Clinical Blues began has been a long winding journey of evolution in the trajectory of Ajayi’s literary journey. His poetry has, two collections later, moved away from the four walls of the hospital and from the political scene which Ajayi criticised, and acquired a more comfortable skin of personal experiences.

Dami Ajayi has been to three continents, acquiring new experiences, particularly of the beginning and end of the euphoria of falling in love. And in all those years, his poetry has worn the garb of all those experiences. Presently, he has been living in the United Kingdom (UK) for over two years, working as a Psychiatrist in the National Health Service (NHS). In those two years he has written dozens of music reviews for The Lagos Review which he co-founded with the novelist, Toni Kan; he has also co-founded another literary outfit, Yabaleft Review and most recently published a third collection of poems titled, Affections and Other Accidents. Asides being a poet, Ajayi is a versatile cultural critic. Ajayi’s penchant for having conversations about music stems from the endless engagement he has with music. Around the same time his poetry took a turning point, he grew weary of what he calls the “tired cultural journalism” in Nigerian newspapers at the time. “I like to write about music,” he says, “because I think the art requires a bit of intellectual engagement with the music, a sort of framework—or a scaffolding if you may.” It was the age of blogging, and so while others opened blogs for documenting their life stories, journeys, and for gossip, Ajayi started a blog where he regularly published music reviews.

Upon the publication of Dami Ajayi’s third collection of poems, Affection and Other Accidents, I sat with him on a Google Meet interview, and we talked for an hour about his artistic vocation as a poet, insights gathered from years of painstaking and consistent practice. At the height of our meeting, he tells me, “The duty of a poet is to give language to experiences. Poets give expressions to things that are elusive. And a poet is a citizen who should be available to other citizens.” He recognised that there were various facets to poetry–the elitist, and others that are grandstanding. Yet he believes that it is in how well a poet communicates that his poetry succeeds.

Even as a shrink frequently engaged in his medical practice, Ajayi has continued to write consistently. Long before his epiphany, Ajayi had been writing since childhood. But it was in his days in Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, he began to meet friends, artists like him too, in whose company he would become a literary innovator, as well as poet. In the university, he befriended the essayist, Emmanuel Iduma and the novelist, Ayobami Adebayo. Medical school for Ajayi, like for many others, was a long, hard battle with an intimidating bulk of academic work and medical rounds. In those years, his creativity underserved him, and whatever little he managed to write were rejected by literary magazines; an experience that he, alongside his friend, Emmanuel Iduma responded to by establishing Saraba Magazine in 2009, to publish themselves, alongside other younger writers struggling to get published, which they did for 10 years.

Ajayi grew up in Lagos as the eldest child in a family of four children born to parents who were both teachers. In the world of his parents, he was exposed to the booky and didactic life of academics. But in the life of his grandparents, he was exposed to a contrast. They, unlike his parents, did not have much western education, and lived in a syncretism between the traditional Yoruba way of life and Western Christian culture. Living in between these two worlds afforded Ajayi a broader worldview. Ajayi and his siblings lived with their parents at farther ends of Lagos, which kept them on the road for hours every school day . In those long commutes he would keep himself busy with novels. The world of many writers made an impression on him, but he was often lost in the world of Cyprian Ekwensi’s novel. He often read at long stretches, continuing long after he got home from the long journey from school. “I could begin a novel today and finish it the next morning.” Along the line he warmed up to the books of Soyinka and Achebe. Okigbo’s poetry would join his long list of literary influences much later because it had been too obscure for the younger reader that he was.”And you know,” he tells me with a lighthearted laughter, “Okigbo’s poetry is not the faint hearted.” But it was West African verse, an anthology of poets from all over West Africa which exposed him to a broad spectrum of poets which awoke in him, the zeal to write poetry. Under the shelter of these influences, a medley of his love affair with Fela’s music, and through the guidance of poets and critics like Tade Ipadeola, Peter Akinlabi and Benson Eluma, his poetry found its feet.

If Ajayi’s first collection of poetry was a product of a new vision of the world, written from a craft partly borrowed from his myriads of influences, his latter collections became an expression of him singing back to the world of his personal observations as he sheds off the grip of influences. “One thing I can say has changed in my poetry since 2007,” he said, “is that I have weaned myself off the anxiety of influences.”

It is in Ajayi’s second collection of poetry, A Woman’s Body is a Country that he first begins to write the poetry of affections. The poems there mirrored the life of a retreating bachelor writing about his itinerary across different countries in the world in pursuit of his fount of affection, alongside his expression of amorous monogamy, and the more light hearted poems of enjoying life over bottles of beer and camaraderie with friends. In hindsight, one finds that it was in A Woman’s Body is a Country that the world in Affections and Other Accidents began. And the latter was born by the implosion of the world in the former and the poetry in the latter stems from the poet coming to terms with this fate.

Affection and Other Accidents sees Ajayi’s catharsis swing further than ever. The collection is, among other things, about heartbreak and the irrepressible pain of the loss of love, but the whole collection follows a storyline, in the beginning and in the interlogues in-between sections of the collection. He is deeply engrossed in his own affairs while being aware of the world outside. He begins with heartbreak, and then he proceeds to give language to his other experiences where he talks about prolonged bachelorhood which is intertwined with the story of heartbreak. In “Aubade to My Greying,” he writes, “I imagined it differently:/ toddler daughter pruning my facial garden/ notices a speck/ & says, “Daddy see.”/ But my progenies don’t breathe air;/ they sit on shelves/ & I wear/ proudly the badge “Author.” And in many such poems like these, Ajayi looks inwards, and unearths art. But the subject of the collection does not end with the inward gaze. One cannot properly reflect on what goes on within without talking about the external factors which impact the intrinsic world. And so Ajayi muses about the beauty, sadness, regrets, pains, but between each gasp,the storyline continues in the interlogues. “Three years/ & four proposals later/ we stand annulled/ a premarital divorce.” And in the interlogue which follows, the poet laments, “It is still surreal/ that you did me dirty/ in five cities.” In the fourth interlogue he asks “& what is love without reciprocity:/ that boomerang effect,/ with the mathematical integrity/ that what you have given/ is it given back?” And in the final interlogue when the lamentations seems to be far gone behind the poem, he writes, “…in the days we spent in Cologne, I felt like I was carrying an extra weight…” of unreciprocated affection, and the pain of the memory when one looks behind and remembers the heaviness.

Talking about the other accidents in this collection, they are constituted by the random occurrences that have happened in the few years in which the collection has grown. Ajayi writes about COVID-19, from the vantage of discomfort of having to always put on a nose mask, political correctness from the vantage of a lover who refuses to make love to R. Kelly’s music plays in the background, the memory of childhood innocence from the naivety of believing that pregnancy was a product of God opening his mother’s womb to put a child there.

While Affection and Other Accidents is the result of an explosion of compressed emotion, and meditation on life, an attentive reader discovers sooner or later that this catharsis was preceded by silence. The confidence to pour out personal feelings comes from the clarity of seeing the futility in holding back. In “The Anatomy of Silence” which first appeared in Ake Review in 2019, and was performed at the Ake Arts Books Festival that year, Ajayi asks, “What do I accept from this silence? / This silence that lacerates peace, / this silence, anathema to bliss// This silence, pensive, dramatic/ amping tension, wrecking intention, / this silence, / violent & vicarious, / this silence between two lovers &/ two phones. //This silence seems to say something,/ my bunny ears cocked at the angle of a/ murderous gun,/ I can’t hear you/ I can’t hear/ I can’t. When one arrives the realisation that in pain, silence is not golden, what follows is an expression of breaking the silence. And breaking the silence is part of the long process of forgetting. Salawu Olajide likens the emotional engine of Ajayi’s collection to the line, “Love is short, forgetting is so long” in Pablo Neruda’s “Tonight I can write.” The long road to forgetting often began with silence with the belief that silence swallows memories. But then comes the realisation that silence accumulates it until it bursts into fits of cathartic confessions.

In this collection, Ajayi is leaning towards the obsession of the confessional generation of writers. His personal experiences and emotions are the fodder of his art. They are at the forefront of his emotions and he is not coy about expressing them, he is not bothered to use the cryptic flagellation of expressions which is the privilege of the poet. He comes as he is, bare and accessible to everyone, as he believes poets should. He condenses pain and self-expression in such simple and powerful terms. And while his poetry is as contemporary as that of the younger generation, it does not fall prey to the monotony of voices for which the confessional generation of poets have so often been lampooned.

Ajayi has evolved from aspiring towards grandness towards clarity. His evolution is demonstrative of how a poet can go from being preoccupied with aesthetics, to being preoccupied with clarity. Perhaps, in doing this, the poetry is sometimes too prosaic, but the message is coming out clearer. It also displays a poet charting different levels of artistry with his poetry, from philosophical lyricism, to the territory of a citizen giving languages to his experiences, and now to exploding pressurised feelings on lettered pages. A poet is inspired by almost everything he experiences. The experiences that have the most profound effects, he chooses to communicate. His choice is influenced by what role the poet believes he should play. The roles often change and his poetry changes alongside. Okigbo came to see himself as a town-crier, and his poems were messages preparing everyone for what was to come, Osundare saw himself as an activist called to expose the unfair inequalities between the upper and lower echelons of the society and so his poems were a conscientious to an unfair society, Okot P’Bitek was a satirist who felt the world even with all its tragedy is better looked from the lens of satire. Ajayi is the essential lyricist inspired by grand ideas of music and aesthetics, who has evolved into the role of the essential citizen that he is even playing the role of communicating with other citizens. Now in his poetry, he is so transparently given to language, culling up personal experiences glaringly. The evolution of Ajayi’s poetry takes the trajectory of the reptilian motion and growth, moving through a zigzag of thematic concerns and shedding the weight of influences, to reveal, what deep down, lies in the poet.

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera’s work has appeared in Jalada Africa, Brittle Paper, Havik, Fortunate Traveller, Kalahari Review, Afrocritik and elsewhere. He is interested in constant intellectual engagement with African literature and culture, and its numerous innovators. Follow him on Twitter @ChukwuderaEdozi