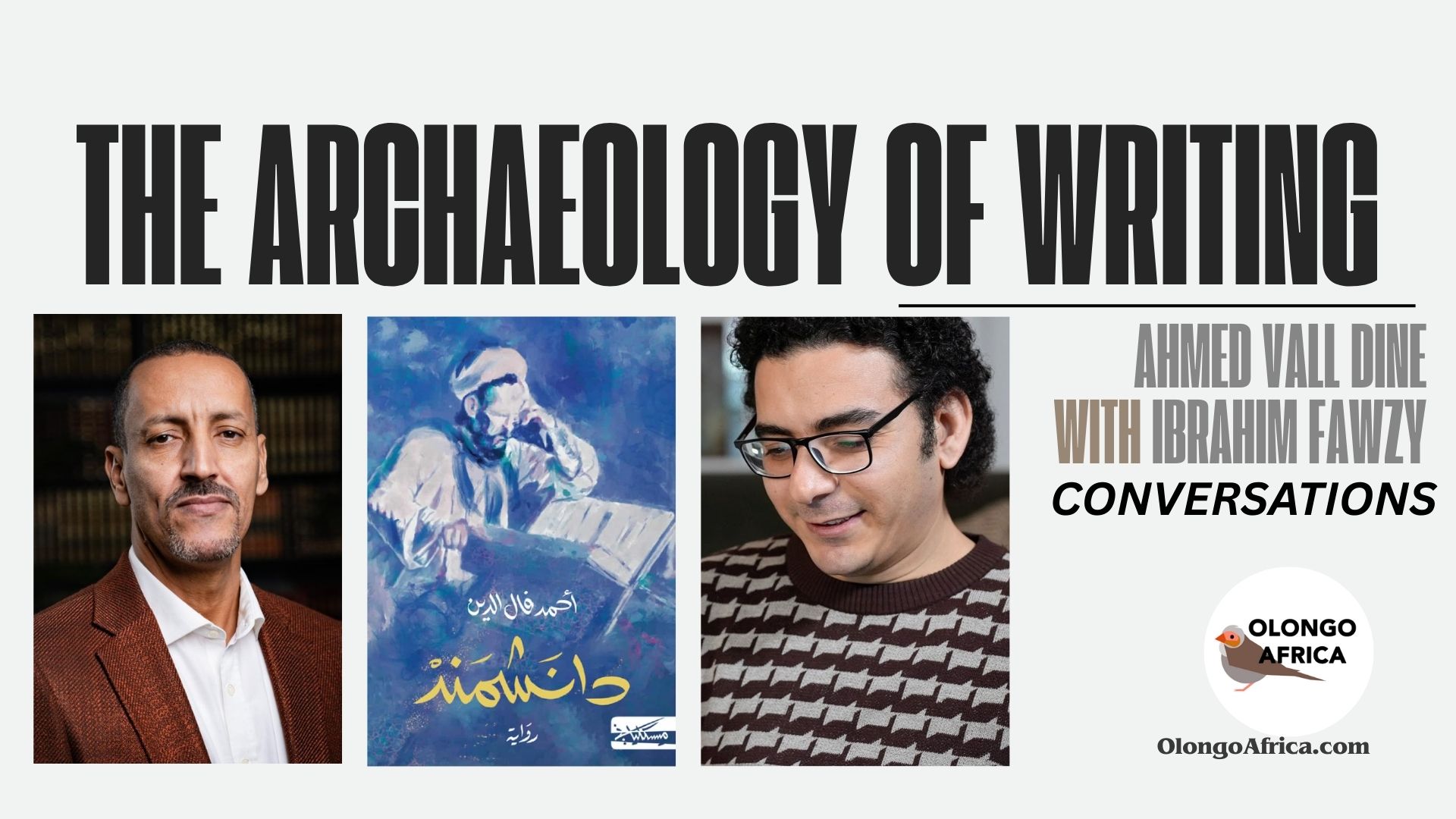

The Archaeology of Writing: A Conversation with the Mauritanian Writer Ahmed Vall Dine

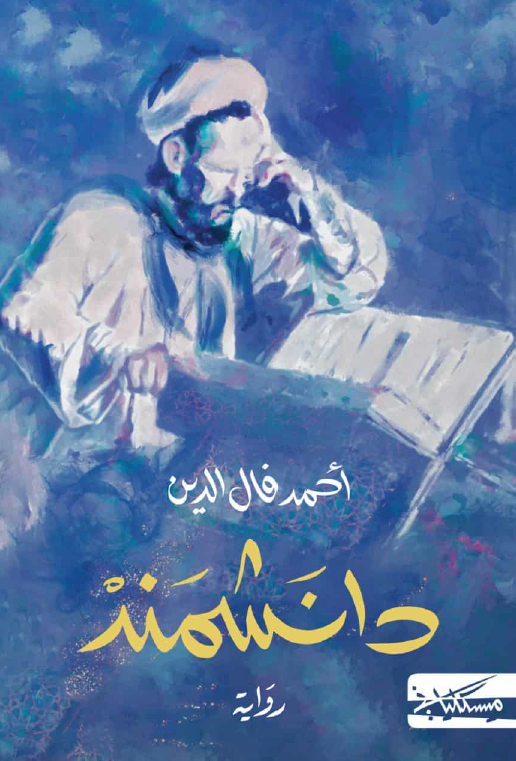

Following a milestone achievement for Mauritanian literature, Ibrahim Fawzy interviews novelist and journalist Ahmed Vall Dine. His novel, Danishmand, has secured a coveted spot on the 2025 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) shortlist, making Vall Dine the first writer from Mauritania to reach this stage since the prize was inaugurated in 2007. Danishmand is a richly detailed historical narrative charting the profound spiritual and intellectual journey of Imam Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali, a towering figure of 12th-century Islamic thought. Ahmed Vall Dine’s diverse body of work also includes the novels Al-Hadaqi (2018) and The Old Man (2019), and the non-fiction account In Gaddafi’s Clutches (English translation by Nicole Fares, 2024).

***

What inspired you to write Danishmand? And what was the process of writing it?

The idea for the novel probably took root in my mind during my first reading of Al-Ghazali’s seminal book about his intellectual journey, Al-Munqidh min al-Dalal (Deliverance from Error). I read this existential text when I was a teenager on a secluded farm in my village in Southern Mauritania in the summer of 1995. The text ignited my imagination with its story of the greatest mind in Islamic cultural history, abandoning wealth and fame, and disappearing in search of spiritual salvation. I imagined him, with my childish imagination back then, wandering through the cities of Baghdad, Damascus, and Jerusalem, unrecognized despite his towering intellectual stature. Perhaps that imaginative seed continued to grow unconsciously within my mind until I poured it onto paper in 2023.

Why did you choose this title, ‘Danishmand’?

For real, choosing a title for any of my novels is usually an arduous task, much like naming one of my kids. My main criteria for titling a novel is the title should hint at the protagonist or the central message. To put it another way, it insinuates the meaning, with an ambiguity that flares up the readers’ curiosity. That’s why, after much hesitation, I settled on the Persian word ‘Danishmand,’ which was al-Ghazali’s title. People in Baghdad and Nishapur called him ‘Danishmand’ when he was a leading figure in education, fatwa, and writing. Back to al-Ghazali’s time, ‘Danishmand’ was similar to today’s ‘Professor.’ However, despite its foreign origin, it was frequently used by his Arab students.

What does this particular historical period in Islamic history allow you to explore?

This was a period marked by the duality of political collapse and intellectual flourishing. Al-Ghazali’s life coincided with immense struggles between different factions, such as the Seljuk princes, the Ismaʿili Batinis, and later the Crusaders. While the political atmosphere was a bit of conflict and strife, the intellectual atmosphere was one of debates. Mosques were full of scholarly assemblies; Sufi lodges were filled with worshippers and hymns. There were many libraries in the great Islamic capitals. This duality of political collapse and intellectual prosperity clearly shows the limited connection between the state and society in the Islamic world at that time. People were far away from politics, as the state hadn’t yet interfered in all aspects of life, as we witness nowadays.

What kind of research was involved in this book? How did you go about doing the necessary research? What were your primary sources? How did you balance historical material and your own creative process?

This is a good question. Writing a historical novel requires a toilsome research since it requires a deep understanding of all the facets of the era you’re writing about: political, social, cultural, etc. The political mood must be present, the intellectual atmosphere must be accurate, and the social details must be true. Those details mold the writer’s efforts into an archaeologist’s excavating work. Therefore, while writing Danishmand, I consulted a bunch of references from history books, such as Al-Dhahabi’s The History of Islam and Ibn Athir’s Al-Kamel, and books about histories of cities, such as Baghdad, Damascus, and Nishapur, to travel books authored by travelers who passed through these regions during the period in question. To be immersed in al-Ghazali’s views, moods, and impulses, I read all of his books, except for his books on jurisprudence in which his innermost thoughts are hidden. This research also led me to devour the most recent studies about him in languages other than Arabic to see how his thought is interpreted. In fact, this is an exhausting journey, but it was the most enjoyable part of the writing process.

The novel depicts characters grappling with uncertainty and seeking truth in a world of conflicting ideas. It suggests that truth is a journey rather than a destination. Can we classify it as a Sufi novel?

Of course, since the protagonist is a Sufi who spent his entire life defending Sufism, it is a Sufi novel. Al-Ghazali tried to prove that reaching Allah happens through the journey towards Him, not through logical deduction. Therefore, the novel is an in-depth Sufi journey, but it is Sufism that stays true to Al-Ghazali’s spirit. For this reason, it is considered a Sufi novel; a Sufism that falls within what is called Sunni Sufism.

How did you write a character like Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, who underwent intellectual and spiritual transformations?

I tried to grasp it by focusing on the questions that haunted him at each stage. The questions of the period when he was rushing to quench his thirst for knowledge differ from the period of seeking fame in Baghdad, which surely differs from the period of doubt and confusion. Likewise, the period of Sufism is different from the preceding ones.

Can you elaborate on the relationship between religious scholars and political figures?

The relationship between the scholar and the politician has been complex since the early days of Islamic civilization. A scholar chases an ideal in his mind, while a politician deals with the reality in his hands. The gap often widens between the two as each deepens in the nature of their goals. The period in which Al-Ghazali lived was no exception. Al-Ghazali may have been fortunate early in his life and mid-career to be associated with Nizam al-Mulk (d. 485 AH), a minister who was known for his respect for scholars and his special relationship with them and the Sufis. During the Nizamiyah period of Al-Ghazali’s life, there was an understanding between the scholar and the minister, and harmony prevailed. This was because Nizam al-Mulk had a project to rebuild the Sunni school after it had been struck by the Ismailis. Al-Ghazali was an ambitious young scholar, so they shared the same idea. However, after the minister’s death and Al-Ghazali’s embrace of Sufism, tension returned between Al-Ghazali and the Sultans. This relationship remained marked by caution until the death of Abu Hamid in 505 AH.

Did you envision a specific audience for the book? What do you want the reader to come out with from the book?

I believe the audience for the novel is those who generally love reading, especially lovers of historical novels. Since the novel tells the story of a soul seeking salvation, I think it is suitable for any serious reader. There is no one among us who hasn’t experienced existential anxiety at some point in their life, exactly like Al-Ghazali.

How does your work as a journalist affect and inspire your fiction?

The relationship between a writer and their work is complex and two-sided. Every job often disrupts creativity, but it also enriches it at the same time. A job can hinder creativity because it consumes time and mental effort, but it enriches it because it provides space to engage with people, talk to them, and gain experiences from that. Every interaction with people is ammunition for any serious writer.

What have you learned through your own journey of writing this novel?

I learned that humans are pitiable creatures living in an eternal, repetitive cycle. Each one of us is born and starts our journey believing it’s unprecedented, but in reality, it is exactly the same journey lived by millions of souls before us. Each of us lives the same complex human relationships, faces the same existential questions, laughs and cries for the same reasons. Still, we continue to repeat this journey as if the earth witnesses it for the first time. This is the secret of human genius and its extraordinary ability to forget, but that eternal forgetting is the source of creativity.

What is your favorite historical or Sufi novel?

One of your friend’s quirks is that he isn’t a reader of novels. Most of the books that hook me are historical, religious, or philosophical. But why don’t we consider history or philosophy as historical novels in some way?

_____

Ibrahim Fawzy is an Egyptian writer and literary translator working between Arabic and English. His accolades include a 2024-25 Global Africa Translation Fellowship, a 2024 PEN Presents Award, and the 2024 Peter K. Jansen Memorial Travel Fellowship from ALTA.