Mbari: Interrogating the Place of Space in African Art

Long after the last fire was put out in this old restaurant, the pot goes on smouldering.

The band is in the area designated as the stage, tuning instruments. In a corner, a handful of young artists and intellectuals are arguing over some tedious philosophical point. Eau de Bohème, Édition Afrique. Liquor chases down smoke in more than one mouth. A couple shares an earnest conversation. The tuning is over and the music is in full swing. Conversations peter out as the beat draws people to their feet.

It is 1961, the year after independence. The dance floor is a microcosm of the country: young and pulsing, teetering with promise on an old foundation. In another iteration, this bunch will contemplate profound pieces of visual art. In yet another, they will be serenaded by the wail of a soprano or the booming voices of stage actors. There is no art form safe from engagement in this place.

Now the house grows hot with sizzling dissent over some political point. Now it reverberates with belly-deep laughter. Now it quietens as the crowd is saged by some artist on their way to global renown. The house takes on the flavour of a hippyesque commune, with the door open (courtesy of a one-pound membership fee) and the password simply a passion for African art; with everyone extending an artistic hand to uplift everyone else’s endeavour. Artist designs the cover page of translator’s rendition of playwright’s piece; musician scores playwright’s production in consonance with architect’s stage design.

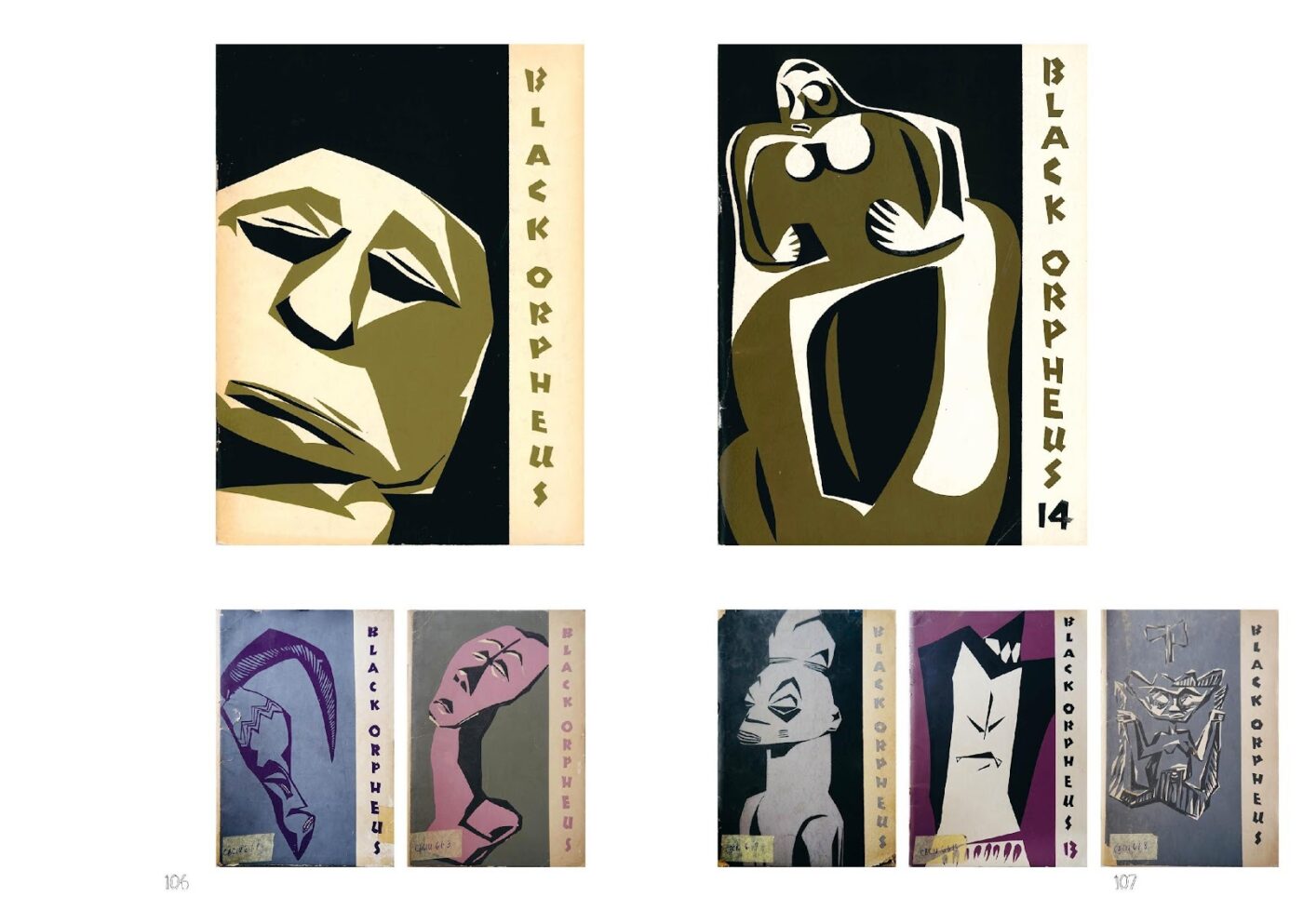

The house breaks ground as the only onsite publisher of local books at the time – books that will end up as classics of modern African literature. Black Orpheus, the first English-language journal on the continent, is older by about four years, but will soon come to be propelled by the flavourful vibrancy of the house.

The house is a pot boiling over with the dreams of a young Africa at dawn, with the shapeshifting of indigenous experiences through colonised lenses into artforms never before seen.

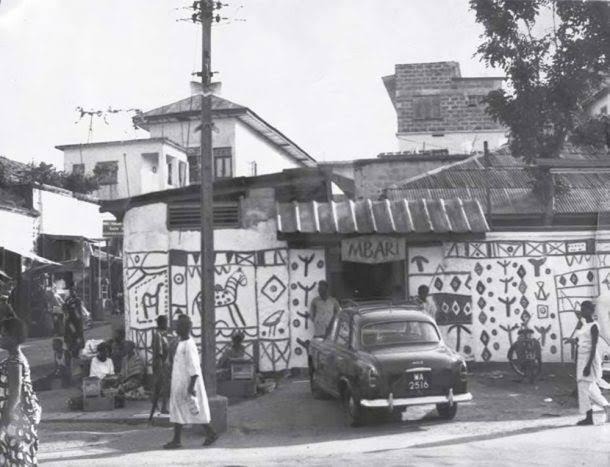

It used to be an old Lebanese restaurant. Now it is the Mbari Club.

The Art of Space

It was Achebe, in a paper titled ‘Africa and Her Writers’, who recalled once saying in a lecture that, “Art for art’s sake is just another piece of deodorized dog-shit.”

We have only our imaginations to rely on regarding what colourful and vehement discourse this statement might have elicited had Achebe uttered it at the Mbari Club. It is of particular importance here, as it seems improper to begin an interrogation of the place of space in African art without first attempting an understanding of what art itself means to the African.

If Achebe is right that “art is, and was always, in the service of man,” then art is the tool with which humanity serves itself wonderment, entertainment, wisdom, truth in all its flavours. Since there is no denying the unsplittable interweaving of religion and art in the African worldview, it would not be farfetched to say that art is one major way the divinities express themselves on earth.

Decades before Jay-Z and Ye crooned the seminal ‘Ni**as In Paris’, writers and artists of Africa and the African diaspora did indeed gather in Paris in September of 1956 for the First World Congress of Black Writers and Artists. It was there that Léopold Sédar Senghor would distil three principles of black African art: its functionality, its poetry, and its engagement of the artist to his society.

Janheinz Jahn, reporting on the Congress for the very first edition of Black Orpheus, summarised Senghor’s analysis thus:

In Africa there is no “Art for Art’s sake”, for even art is social. But Negro art is not purely utilitarian. The African has a sense of beauty. Beauty is to him part of the quality and of the effect of his work. One might call it functional beauty.

There is, perhaps, no better example of functional beauty than the now near-extinct creation ritual of the Owerri Igbo.

#

Thunder strikes. Catastrophe befalls the community.

Ala (also known as Ani), the central goddess of the Igbo, lets slip to the diviner that she is far from happy. A cloud of doubt has lately overcast her pride of place in the pantheon. It seems the people have relegated her to the background. Any wonder she’s been raining down misfortune in her despondency?

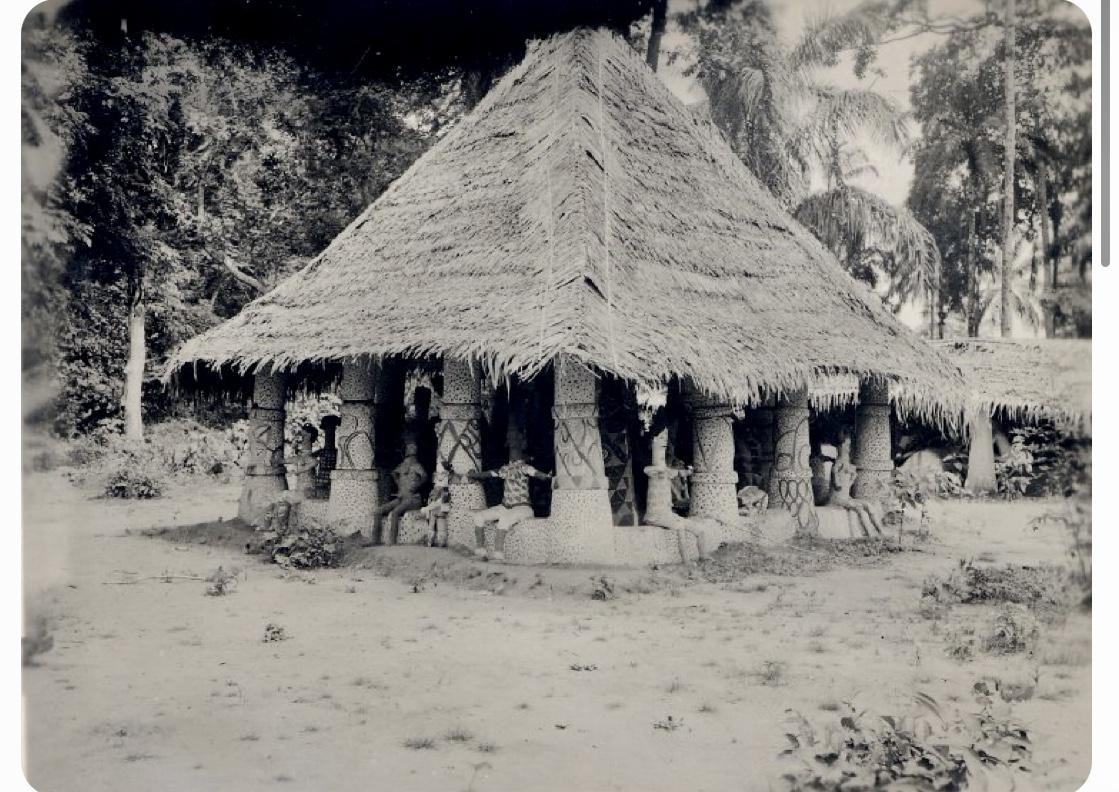

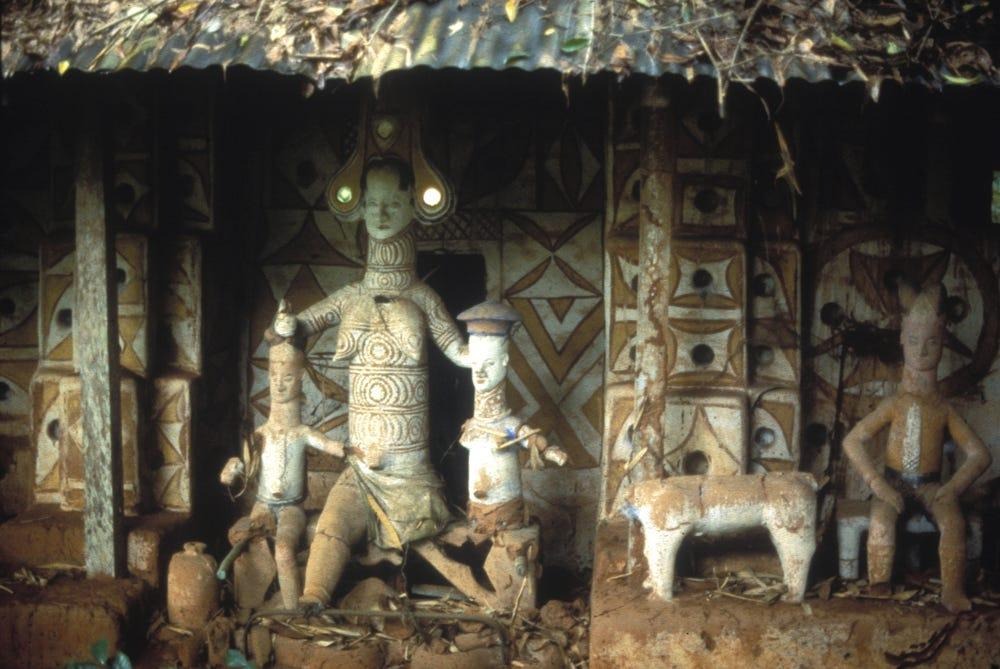

A gong rings out in the dead of night. The community is informed that Ala demands appeasement. The chosen—men, women, youth, aged—hear their names reverberate. They undergo initiation, which transforms them into Ndi Mgbe – spirit workers. They move away from the village, to a place close to the forest, a seclusion fenced off with palm fronds. There they will live and work until the sacrifice is done.

They are not artists, these people. They are ordinary members of society. But for as long as it will last, under the guidance of the master artist and associated spirits, their hands will mould an atonement worthy of the goddess.

Before dawn, they walk far and wide, fetching the desired earth from termite nests. This anthill clay, symbolically named ji (yam, the head crop in Igbo society), will be pounded to perfect consistency. Then they will begin to take shape, guided by human hands.

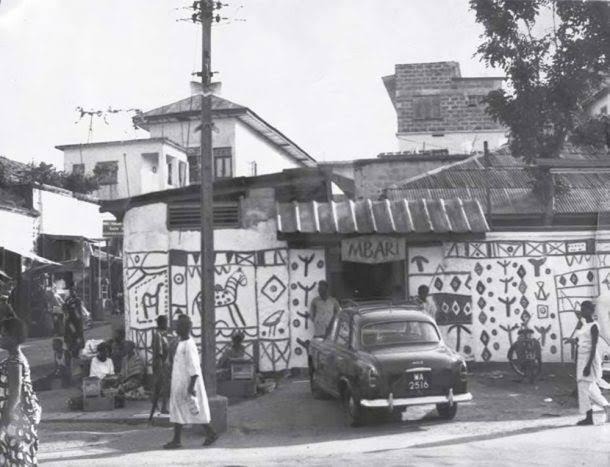

First will come the open-sided rectangular hut consisting of pillars supporting a thatch roof, themselves supported by a step encircling the whole hut. Then a central volt, ruled by the figure of Ala, the image of whom is dictated by the vision of the master artist in charge. Surrounding the pillars will be lesser gods, animals venerated and mundane, humans, items, scenes. In short, a full spectrum of the community’s reality, from divinity to everyday life. The figures are nigh-on life-size, with rather cylindrical forms. Both structure and sculptures will be covered in intricate, mesmerising patterns and motifs in colourful hues.

As this artistic endeavour is underway, the rest of the community goes about its daily life, careful to steer clear of the site and the working group: Do Not Disturb.

At the end of the residency, which can take several months—even years, depending on the intricacies of the master artist’s vision and/or the spirits’ leading—the spirit workers are repatriated to the clan. Elders and the rest of the community gather before the completed monument, where a festival of life takes place. Sacrifices are made to Ala, unveiling to her the work in her honour.

At the end of the ceremony, everyone returns to the village. The End.

Nobody is expected to revisit the site; in fact, that is prohibited. No maintenance emissaries, no nostalgic trips down memory lane. Life goes on. The plague lifts. Ala is worshipped with vigour, but not at this site, which will, over long years, return to the earth from whence it came.

This is Mbari.

#

Mba = community/society/clan/town;

ri = eat/feast.

Mbari, in essence, a feasting of the people. A festival of creation.

Upon close appreciation, Mbari strikes one as a profound celebration of Space. Space in this context expressing itself in planes of the physical, the communal, the cognitive.

Physical space, in Mbari, is embodied, first by the secluded area the spirit workers inhabit for the duration of the project, and later by the Mbari house upon completion. The communal space takes the shape of the entirety of the people involved in whatever way in the project: chief priest, ndi mgbe, the master artist, even the members of the wider community who give the chosen the wide berth required for the work. The cognitive space becomes the transcendental consciousness of the people, which informs their interaction with both the physical and communal spaces, keeping the former in memory when it falls out of the sensory loop. In the multidirectional nature of movement in the African worldview, these expressions of space are, at all times, intertwining. While the physical sometimes subsumes the communal, the communal transcends the physical. The cognitive is the link that straddles both.

It would be remiss—nay, reductionist—to believe that the essence of Mbari is merely the completed structure at the end. The phenomenon that presents itself in the end as Mbari starts with the deity’s request. It blossoms as the chosen people pound and mould and paint clay into a ritual. It dazzles into completion at the feast presenting the finished work to the people and dedicating it to the deity.

In Mbari philosophy, then, art is not only the offspring of the congressing of the three planes of space, it is also the congress itself. Space, therefore, is the first principle of art. Art as process, the space that passaged the finished product, the whole. The finished work we call Art becomes a synecdochical symbol representing the whole. An extension of the interaction amongst the planes of the space it was created in.

Space as Chaos

I am at a screening of Ebrohimie Road, Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s documentary on Soyinka’s time and art in the eponymous location. In one shot, we are shown a museum collection of African art. The museum walls are white, the monotone background a clean but dreary contrast to the art it is sporting. I turn to Skodo, my neighbour, and we have a brief exchange on the impersonal, soulless space of the museum, and of museums and galleries in general. Pristine and unalive.

How does such an environment bear upon us as we engage the pieces of art it hosts? One may argue that the pared back designs of these spaces allow us to focus solely on the artworks without distraction. But whenever has art—in its creation and its consumption—been a thing successfully abstracted from space?

Take, for instance, a typical masquerade festival in an Igbo community. The festival takes place in the village square. There will be the usual towering ancestral tree, ranging in location from centre to right at the edge of the square. The ground will be swept clean by a younger age grade, and attempts at levelling it out will be visible, but it will remain unlevel anyway. As regards seating arrangements, provisions will most likely be made only for the drummers et al; most of the community will be content to stand. And stand they will, in various shades of disarray. They will form a ring around the square, in the centre of which the masquerades will dance. The crowd will surge into this space from time to time, to get a better look, a better feel, of the procession of spirits. They will now and then be chased back by masqueraders, which will result, depending on the turnout, in stampedes ranging from nonexistent to potentially—even outrightly—dangerous.

In short, a masquerade festival is the antonym for immaculate. And that is the entire point. It is all that chaos that makes the festival. The rippling surge of the crowd, their hollers that sometimes drown out the drums; the dust from stampedes of feet; the abundance of spirits gallivanting, lashing out; the all-around disorder. The milieu is the festival. Take that away and what you have is a scholarly procession of masks and cloths.

It is open to debate, but there is perhaps no better expression of the sublimity of chaos than the thing that Fẹlá Aníkúlápó Kuti did with music. Afrobeat, his enduring and magnificent legacy, is not one thing, nor is it two. Fela, in life and in art, was the maximalist manifesto, Trump’s Big Beautiful™ in the flesh; stretching out to imbibe influences from wherever inspiration sprang, transmuting those into unheard-of sounds, of the Achebean prophetic flavour.

Fẹlá deployed multiple instrumentalists where singles had sufficed for bands before him. His songs regularly grazed and surpassed the half-hour mark (though you’re likely not to notice as you tap and nod and shimmy along), which was arguably natural, since they took a village-size entourage to perform.

Where else did the prodigy debut as bandleader if not the invigorating Mbari Club? Afrobeat at its perfection took years and a multitude of influences to craft, yet there is no denying how decisively that melting pot of ideas and perspectives and personalities and philosophies and sheer creative outburst inspired Fela in his early years. In fact, he would go on to model his famous Afrika Shrine in part after the Mbari Club, seeking to recreate the alive and vigorous engagement of that space that had so nourished him in his early days.

All this not to say that there is no place for quiet, for the simple, for the minimal in art. But the obsession, particularly Western, with the immaculate, the perfect, the optimal, necessitates a chaotic apologia. Art, after all, is all about balance. There is a place for the secluded residency where ndi mgbe navigate clay under spiritual guidance, where the band makes its practice. And there is a place for the feasting, the riot of life.

Space as Access

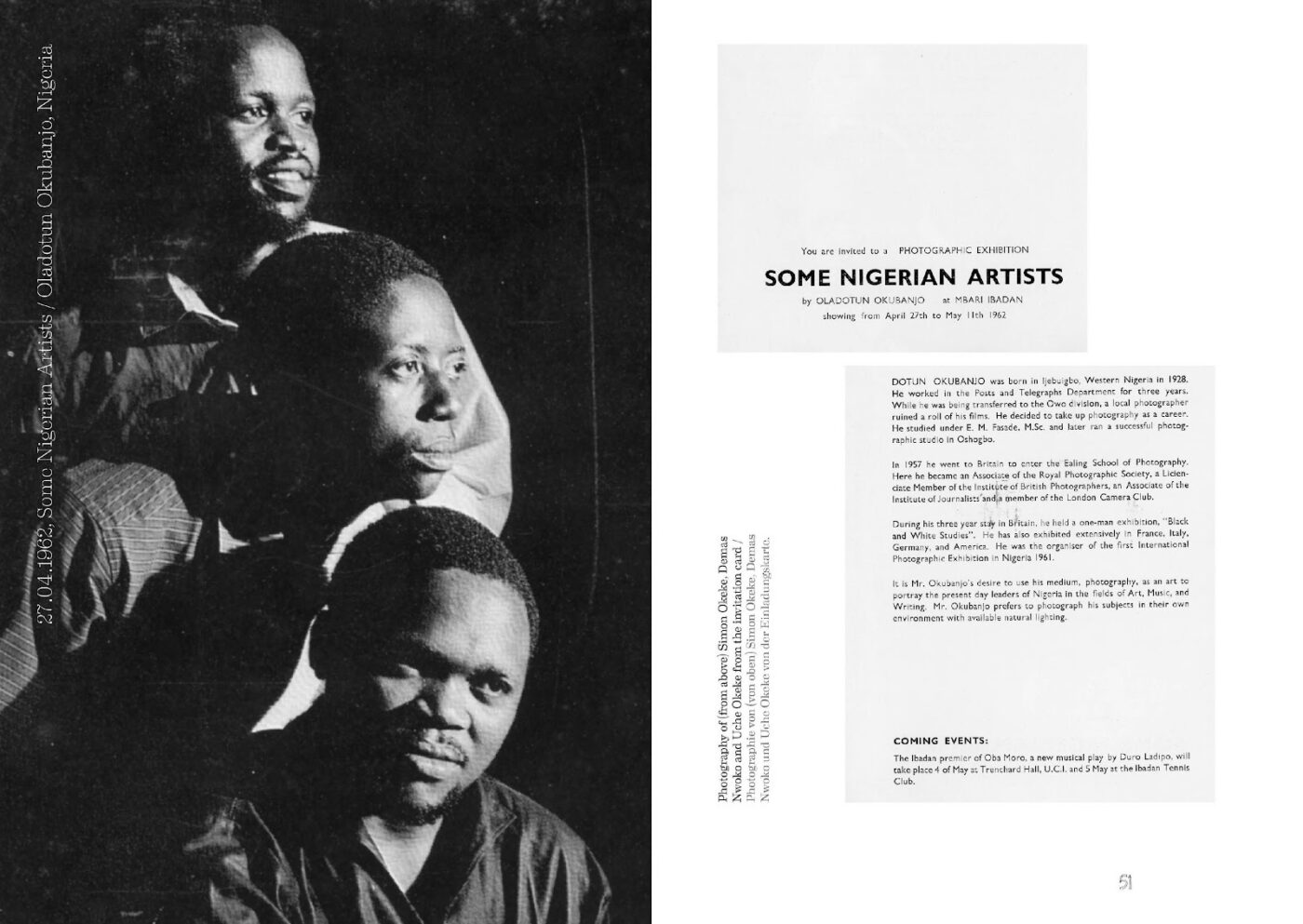

The Nwokike Literary Club of the Enugu campus of the University of Nigeria is a 21st-century institutional version of the Okike Journal founded by Achebe in the university’s main campus in Nsukka in 1971. The year right after the end of the Biafran War. In the aftermath of that most aching period of our history, Achebe understood, in a visceral manner, the need for a space for artists to gather and attempt to make sense of an existence that was, more often than not, senseless.

Nwokike is a creation of the late Dr Chika Nwankwo of the Nigerian Literature course at the school, herself a former student of Achebe. Nothing elicits nostalgia in my heart when I think of university quite like Nwokike. Wednesdays, four to six in the evening, were spent listening to magical words by students grappling with the start of adulthood and all its entrappings; the mostly gaudy monstrosity that is studying in a Nigerian university; the exhilaration of youth and love and hurt. We would critique works and have fiery discussions and challenge ourselves to write better, think better.

Nwokike is an important influence on my writing art. That exposure to a community of like and unalike-minded people with varied experiences and depths of perspective afforded me the opportunity to stretch my perceptions of what was possible as a matter of creativity.

It did not end in that lecture room on those Wednesday evenings. The official WhatsApp group of the Club was, on some days, even more bustling than the classroom convention, with members who were unable to make it to physical meetings able to jump into discourses fresh or carried over from the previous Wednesday.

As modern peoples continue to confront obstacles to physical communion faced by their ancestors as well as new ones of their own, digital spaces emerge as an antidote. There is the argument, perennial, as to whether the digital trumps the physical, or it is the other way round. There are questions of preference, feasibility, efficiency, and the science-backed benefits of face-to-face communication. But the things that are true for physical space remain mostly transferable to the digital. Online magazines, readings, in-conversations-with, etc., all strive to provide artists with that same petri dish which art requires to culture. Community, future-proof.

In this manner, Space becomes synonymous with accessibility. When we gather, one has access to what one may not have had, by the simple virtue of another being present. This is true for—and is one of the guiding principles of—Black Orpheus, essentially a manifestation of the dream of its editors to make available to the (primarily Anglophone) African the renowned works of their siblings on the other side of language as well as geography.

Per the editorial in the very first issue of the journal:

It is still possible for a Nigerian child to leave a secondary school with a thorough knowledge of English literature, but without even having heard of such great black writers as Léopold Sédar Senghor or Aimé Césaire. One difficulty, of course, has been that of language; because a great deal of the best African writing is in French or Portuguese or Spanish. “Black Orpheus” tries to break down some of these language barriers by introducing writers from all territories in translation.

“Black Orpheus” will also publish the works of Afro-American writers, because many of these are involved in similar cultural and social situations and their writings are therefore highly relevant to Africans.

The decline of artistic space in any society, then, heralds the decline of critical thinking, of intellectual progress, of leadership accountability, of social wellbeing. The neocolonial governments of post-independent African states, with a view to personal enrichment and the people’s impoverishment, understood this causal chain better than most, with the result that artistic spaces and publications were often the target of government crackdown, harassment, and closure.

The society that does not cultivate space, asks that it be crippled.

A late March evening. I am outside, looking up at the sky, pondering the paucity of stars, wondering how to approach this essay. In a sudden haze of gratitude, I think to myself that it is so wonderful to be able to devote oneself to just reading and thinking and writing; to be supported in that endeavour.

Sometimes, space takes on the form of opportunity, aegis. In this instance, the visionary OlongoAfrica by way of the Black Orpheus Fellowship.

Space as Communion

Everyone scurries to the front of the hall. We all know something truly remarkable is about to begin. It is the second day of the 2025 edition of the Umuofia Arts and Books Festival, named after the fictional village in Things Fall Apart and convened by Chiedoziem Chukwudera. The exceptional artist Igbobinna Eze is about to draw. Live.

First, a preset canvas is propped up on an easel onstage. Then comes the music: an eclectic hashing of twentieth-century Nigerian highlife and pop music with Afrobeats rhythms, produced by the artist’s equally brilliant brother, Jvbal. As the spiritual melodies begin to move in the artist, we find ourselves partaking of that usually very private awakening. He begins to sketch.

Now he directs strokes masterly across the canvas. Now he pauses for a couple of seconds to contemplate the image in the process of birth. Now he gets away from his creation and seeks counsel in a mask. Now he returns and flourishes and looks to us and we clap at the marvel before us. Too early. He turns back to the canvas.

Furious or frustrated or both, like a great conductor of yore, the artist bunches his fingers into themselves and the music obediently skids to a halt. In the silence, we dare not breathe, feeling as offensive as whatever it is that’s not pleasing to his eyes on the canvas.

He snatches said canvas from the easel and throws it onto the floor, changing orientations, walking around the frame. Pondering. Whatever he is looking for, he seems to find. The canvas is restored to its rightful place, the music is beckoned back, the strokes take on a spirit dance. The drawing becomes an overawing expression. A second time, artist turns to audience. A true end this time. We stand in ovation.

We are in the presence of a master. But the master is also in our presence. How has our company tempered the artist? How has it ignited his madness? Taking our questions afterwards, he confesses that some of the stages in the process were a performance, for our benefit. Going home later that night, I am wondering how much of us is on that canvas, how much of this festival will survive in the artist’s practice. How much of my writing will be flavoured by what I have just witnessed.

Space, front and centre, is the living, breathing people that attend it. As a milieu, it is then not only a place for ideas to sprout. It is a central influencer of the ideas that do sprout. Had I been at an ice cream party, I would have been entertaining different thoughts on my way home.

Mbari houses, whilst sharing principal features, also embody differences striking and subtle. Raw materials will vary in properties from place to place, as will available space. But behind the particularities of each Mbari’s distinguishing appearance is the master artist and their idiosyncrasies, their practice philosophies, their visions. Behind the artist are the chosen of the community, the varying strengths of their grip, their eyesight excellent or no, the spectrum of their dedication. Above them all is the community’s very own deity.

It is an aged claim that art is an isolating pursuit. It is the thing we toil over in the innermost recesses of our souls, shut out from everyone else, even ourselves, lest outside influence taint the purity of the thing we are attempting to hatch in those sanitised conditions. There is no denying the towering need for solitude in the pursuit of art, of a good life, even.

But to favour isolation at all times because one is trying to make something the world has never seen before is to assume that there is a bottomless pit of inspiration and raw material within oneself. While the artist is indeed a river of ideas, the river’s tributaries are the artist’s interactions with the world. A comic encounter, an overheard piece of hot gossip, a devastating heartbreak, others’ art, this earth we walk on and this air we breathe and this water we splash through and this tree we hack at in frustration.

When we acknowledge art as a communal endeavour, we begin to offer Space the revered pride of place it deserves in our contemplation of art, its creation, its appreciation. As with all things in life, we must seek and cradle that balance between refreshing solitude and inspiring communion.

Space as Decay and Regeneration

I am getting ready to travel to Owerri, Imo State, to visit the Mbari Cultural Centre, the last assault of that ancient art form against the obliterating forces of Christo-neocolonialism. My search for information on the Centre yields a YouTube video by Zee On Demand. A few seconds into the video, the vlogger drops the bomb: the Rochas Okorocha administration demolished the Centre in 2016. That is why she is visiting the state’s Council for Art and Culture housing the art gallery housing such a stark collection of artwork as to elicit tears from one’s eyes.

I cancel my plans for Owerri.

Personally, I thought the Mbari in the Centre offensively ordinary, from pictures I’d seen – it had none of the vivacious paintings that characterised the Mbari of old. As for the supporting sculptures, they were unconscionably ugly and did not utilise the space properly. Besides, the permanence of the structure was, to my mind, an affront to the essence of Mbari.

My decision to not visit Owerri anymore was not due to my suffering over the Centre’s demise. What I was grieving was the act of destruction.

The average Nigerian’s disregard for heritage is nothing new. It is either the said heritage is the devil on earth, or—as was alleged in the Centre’s demolition—is standing in the way of, or too inconsequential to consider in, the pursuit of progress (a.k.a. urban development). There is much that can be said about the colonial-trauma foundation for this disposition in our people. But that does not make it any easier to endure.

That was why I did not want to visit Owerri anymore. Space, as a physical manifestation, is a waterpot of forces, a vortex of the energy of acts it has witnessed. I understood this and did not want to make concrete my sense of loss.

That is to say, at first. As I thought more about the Centre and how different it was from the ancient practice, I began to consider another, more ethereal plane to what had happened in Owerri.

Mbari is an embrace of decay and regeneration. A cycle, as all life is. Death and rebirth. This Mbari is given to Ala and left to Ala’s devices, to do with as She will. Another will be given at another time.

Space, for the African, is a multidirectional affair. There is not only the linear plane of birth through life to death. There is the outward (or downward or upward, depending on your transcendental leanings) plane of the land of the spirits, which is the true destination of all souls on earth. There is also the cyclical plane that represents reincarnation, the rebirth of a soul, its return to earth from the spirit world.

With this viewpoint in mind, one can begin to appreciate the African’s approach to art. Senghor’s words at the 1956 Congress come to mind: “The artist ties himself through his work to his people, his history, his country, his time; since he is engaged, he does not bother to create work for eternity.”

If we agree that space, and time, transcend the temporality of life on earth, we must then also agree that the art we make ought to embrace that knowledge, giving itself freely to transmutation, to the flow of the river of time, to the law of transience. To decay, so that it may be reborn.

In this sense, the African understands the futility of the human desire to preserve unto eternity. Modern humanity, it seems, recognises the erasing action of time’s hand, but does not seem to grasp the point of it. So we take up arms against time by way of conservation.

Indeed, history ought to be accessible to those coming after it, that they may learn ancient wisdom and lessons. But, having learnt, we ought to press forward in regenerative propagation of the ways of our forebears, not dwell on mere preservation. The artist must constantly be engaged.

As I thought along these lines, I began to reconsider the destruction of the Mbari Cultural Centre by the philistine Governor Okorocha. In spiritual philosophy, deities will often employ the most unlikely of agents to bring about their desires. Whilst said agents go about believing they are acting of their own will, they do not realise they are merely puppets in the grand scheme of things.

Violent and depressing though the act was, it seemed to me that Okorocha had simply been the termite nest returning the Mbari in the Centre to Ala, its rightful owner – a years-long activity suddenly expedited in one day. The feasting was over at this site. It behoved me, community member, to not revisit. Space as the launchpad that must be moved on from, for growth.

So I moved forward, considering the ways in which I might build an Mbari with my words, my art.

Postscript

There is something alive, some potent thing fashioning itself out in the Mbari Club, in every gathering of artistic humanity. The selfsame thing pervading that fronded-off enclosure of ndi mgbe – atoms of multiforms of energy already volatile on their own, bounding into one another, catching fire, burning bright; phoenixes rearing their beautiful heads up at the extinguishing.

First, there is space. Then art follows.

____

Kosoluchi Agboanike writes fiction, essays, poetry, and plays. Her work appears in Southword, Oh Reader, The Daily Tomorrow, African Writer, and elsewhere. She is a 2025 Oxbelly Fellow, was longlisted for the 2025 Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and was the 2021 winner of the Emeka Anuforo Prize for Best Literary Artist of the Year. She is one of the Black Orpheus Fellows selected by OlongoAfrica earlier this year. She lives in Enugu, Nigeria. Photo credit: Vangelis Patsialos