In Search of Beauty

Even though I walk through the valley

of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for thou art with me.

-Psalm 23:4

On the street where Panseke passes the baton to the uneven boomerang-shaped suburb of Quarry Road where I live, Abeokuta presents itself as a town under. Houses, small shops, primary and secondary schools rise as though from beneath on the left and on the right, lining the street like spectators at a marathon. The walking man feels like he is sinking into a hole one step at a time. Every time I come upon this view, I think of home and its attendant metaphors. The tall red-bricked Agbeloba building that stands at the intersection where the road curves into an L-shape, one edge pointing to the house on the left where I grew up, the other pointing to the place where I live now. Whenever I think about my parents’ house , the first home they built, in their prime, the one I mean when I tell friends I am going home, I think of our family history. Inside that small bungalow, I remember every person that ever walked in or out, the ones living and the ones now in memory, the people whose laughter and sadness solidified the building into a historical relic, at least for those who belong to our clan. I find myself at a crossroads of gratefulness, because there once was a time I couldn’t wait to be rid of the place.

Like many young people in search of independence, I moved out of my parent’s house unceremoniously, soon after I got my first job. I have since changed houses seven times in about nine years in a chase for reasonable rent. Abeokuta landlords have a thing for increasing rents annually and without any discernible change in the service or the facilities. They turn us into hipsters in constant migration. This new place seems reasonable and quiet. The house is bordered to one side by the Ogun River. The house stands like one of the numerous pebbles on its banks. But the river is not really a river anymore, just a sorry pathway for rampaging brown water. People have beaten the attitude from the Ogun River. Constant pollution by the locals and industries, coupled with government indifference, have made sure of it. The rent is fair, but I am already thinking of moving because my neighbours are Yahoo Boys, and I worry that one day the police will come knocking and mistake me for one of them. Police in Nigeria do not care a jot for proper investigations. Being young and independent is crime enough to land you in one of their overcrowded jails.

*

I am disappearing. My face is swelling to a quadrant I don’t recognise in mirrors anymore. I blame it on too much sleep and zero exercise. We are living through a pandemic. There is a total lockdown in effect, with schools, restaurants, bars, banks, hotels and almost every outdoor activity on pause. It’s been two months of waiting for the coronavirus, harbinger of the pandemic, to pack up and leave. But like a proper parasite, we are learning to adapt to its wiles and demands. But staying at home also has its reprieves; my body has started acquiring additional flesh in odd places. The health app on my phone says I am becoming obese. And because gyms are closed, and running is a sport too strenuous for my lazy ass, I have taken up walking again. My doctor says walking increases lung function and decreases arterial stiffness for up to twenty-six hours. I also read in a book sometime ago that anxiety cannot live in a moving target. For an undiagnosed depressive like me, this is enough motivation to embrace walking, because living through the lockdown also means living with my anxiety face to face, waking up with it, brushing my teeth with it, having meals with it and never knowing how to escape it. And it helps that in a lockdown there is little or no distraction and fewer excuses for me to feel the awkwardness of the usual glances that accompany those who take long walks in this town. Abeokuta people have a habit of dressing people down with their eyes, a time-honoured habit that spares no one.

I have found walking as enjoyable as I once found cigarettes. It’s almost as if the farther I go, the more my body forgets its knowledge of fatigue. Walking is helping me to learn the language my body speaks. When I was a teenager, walking alone on random Abeokuta streets fascinated me. Strolling through the streets of Ita-Eko and Ijeja I’d watch people in their mundaneness. Broda Kola haggling his rates with customers at his barber shop, Iya Tisha in battle with her noisy Singer sewing machine, Broda Jide and Aunty Comfort stealing kisses behind the grocery counter thinking no one was watching. My eyes would sweep over the blues, the greens and the greys of my neighbourhood as I walked. I was invisible to the people, as I often spent hours at a spot, following everything happening without anyone confronting or asking me to leave. It was as if they had gotten used to my eyes on their bodies, or they just didn’t care. The only person who ever noticed me at such times was my brother, and he thought I was creepy. I sometimes wonder if this habit is the reason writing chose me. But as I grew older, invisible became impossible. So I adapted. As a child, I could only walk the length of our street because my mom would beat the shit out of me if I went anywhere further. As an adult, I have freedom. I can go from neighbourhood to neighbourhood, carrying a notepad the size of an international passport, documenting my city. No one cares too much about a walking man if he doesn’t linger too much.

*

I am an early riser. Recently, however, I have found that my sleep is only ever sweet just around the time I’m to wake for my walks. Getting out of bed becomes a chore in itself and I struggle with it. For over a week, I have been doing a minimum of five kilometers every day. This walk would take me from my house through Àgbẹ̀lọba, straight up the hills of Quarry Road towards the Bridge of Confusion in the Post Office, from where I would turn into Ita-Eko via Ita-ìyálóde and then back again into Quarry Road and then home. This always earns me extreme fatigue and fire in my calves. Today I want to push for double the quota. It is Thursday. The weather is fine. The rains of last night made sure of it. The soft breeze caresses my face as I begin the climb out of my street. At the beginning of the pandemic, we searched for rain and couldn’t find it. We thought perhaps if it rained once or twice it might wash the coronavirus away. The irony of it. We never really cared about the environment until this pandemic, and yet it is to nature we turn at the first sign of trouble.

Once on the main road, a ray of sunlight bites the back of my neck and an eeriness washes over me. Quarry Road, like many other suburbs in Abeokuta, is negotiating a new identity for itself. Before the virus spread to Nigeria and entered Abeokuta, this road would throb with a cacophony of sights and sounds. From the green and yellow of taxis to the noise of their tyres in conversation with asphalt, to schoolchildren in their rainbow uniforms, their chatter contributing to the music of the moment. Now Quarry Road is a graveyard. The loudest sound you can hear from afar off is the chirping of the laughing doves local to the town. Their warble would ordinarily be drowned out by human activity, the sounds of man and machine. Now the birds call to each other without a care in the world, and the wind carries their voices no matter the distance. I find myself jealous of their reckless abandon. No such recklessness for us humans for a while. This pandemic has made sure of it.

As I begin the climb towards the Post Office, I start to see people. Men and women with gleaming bodies hugged by sweat. I imagine they must have been jogging some really long distance. I wish I could be like them, and though I am dressed right, I know I would jeopardize my plan to cover a longer distance if I joined them. As they run by, each person eyes me — the rest of their faces hidden by the facemasks health experts advise we wear. It could pass for a kind of greeting, the eyes, but for me, more like an acknowledgement. To live through a pandemic is one thing, but to continue your journey towards fitness in anticipation of a future, despite the impossibility of everything, is some gangster level of optimism. The kind of encouragement I need as I continue on my walk.

*

The thing about walking that’s often unacknowledged is how a city’s personality opens up to you. In Accra, Ghana, last year, during a small literary event organized by Pages & Palettes and Ghana Writes, my friends and I decided to take a walk around the Greater Osu area where we had lodged. This was to give us a chance to stretch our legs and find a place where we could get an inexpensive breakfast. The preceding days that brought us to the city had been tumultuous. An exciting road trip of two days had stretched to three, because of corrupt customs officials from the Nigerian border down to the Togo-Ghana border. It didn’t help, also, that we had to share a bus with some Ghanaians who left their xenophobia inside their pockets until our bus skidded into their country. They accused us — the Nigerians — of being unruly and religionless. They complained about the alcohol we drank and insisted we put out our cigarettes. At the border to their country, they pointed us out to officials who came to pat us down and warned us not to stay a day over our proposed dates of departure. So we arrived in Accra with our fists clenched and our legs cramped.

That morning as we walked, the Accra sun arrived early, striking us with its rays, as if keeping its eye on us. We had walked about two hundred metres from our hotel when we met a man who had the face of someone who kept a ledger of his misfortunes but was quick to always try again. I don’t know what caught his attention, perhaps it was our Nigerianness. Someone once told me there is something distinct about Nigerians, something that sets us apart from every other black person in the world. The person never told me what this thing was. I reckon this was what the man saw as we approached. He walked up to us and offered me a stick of cigarette. He must have seen how my eyes lusted after the one stuck between his lips. He told me he was an artist and insisted we visit his shop. His roadside store was a shack that smelled of illicit gin and dirty rain water. We sat by an empty shack beside it, and watched as the man rummaged through his portfolio of artworks to show us the ones he thought we might be interested in. He spoke of his love for Wizkid and Davido and did his best impression of their songs. He shared his love for Nollywood and opined that the Ghanaian movie industry wasn’t far behind the Nigerian one. It was refreshing to hear a non-Nigerian gush about our country and culture. He showed us where we might get food and offered to help us find weed. And though we neither bought art nor took his offer to find weed, his kindness was a sweetener to the bitter tea that we had drunk on the bus ride in. .

*

I have become the reluctant lover. When you wake up every morning to commute between two extremities of a location for a long time, this might happen to you also. What’s more interesting is how on this walk, with the city devoid of its usual suspects, I find myself falling in love again. I see the city in all its colours. From Omida to Isale Igbein, there is a beautiful slope of high and small buildings demarcated by a long snake of a road which starts from Gbokoniyi in Onikolobo and crescendoes around the big roundabout adjacent to Ake Palace. Abeokuta has changed from the little town of Wole Soyinka’s famous book, Ake: The Years of Childhood, yet in its newfound modernism, the city has retained most of the nuances that made it worthy of being immortalized by the Nobel winning writer. I have walked most of the places in the book: from St. Peters Cathedral to Sacred Heart Catholic Hospital to Centenary Hall — remnants of colonial occupation — like a pilgrim, but I have found that for me to truly know this town, I must seek out its beauty for myself. I guess this is what falling in love must feel like, seeking your own definitions and finding your own meanings.

*

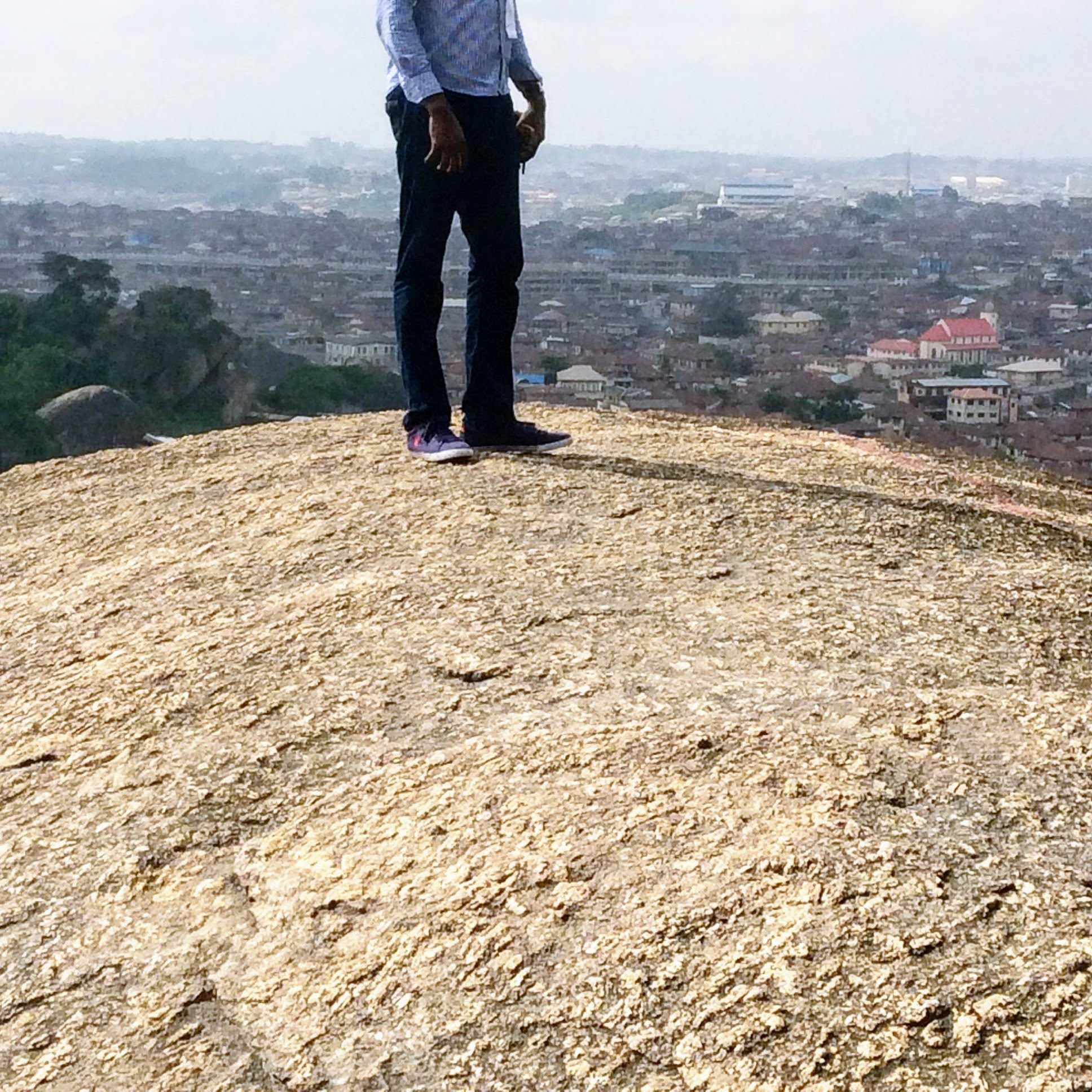

There is a song by Chief Commander Ebenezer Obey in tribute to Abeokuta. A song etched into my memory not by choice but because my father is a superfan of the musician. The song begins with the combination of a dexterous lead guitar and drums ushering in the chorus before Obey joins with his vocals. He begins with a call and response in praise of the incredible Olumo Rock for which the town is named. He goes on to ask a question that has lived with me since the first time I heard the song.

“In what way would you experience this place without climbing?” For years, this question only held a meaning for me in the literal. It reminded me of something a friend said to me years ago. He had been visiting Abeokuta for the first time and insisted we ditch the taxis and take a walk around the Itoko/Olumo area, saying this was the only way he knew to experience a place. “When you walk this city, you will always climb,” he would later say. But when Obey said this about Olumo Rock, he was also being philosophical. He was talking about how the town can invoke in a person the propensity to always look ahead, to believe in the possibility of pushing one’s self out of his circumstances and anticipate some form of elevation.

So for most of us who live here, we are always looking ahead, to a chance for some sort of propulsion. But there is a way in which this expectation has played out in recent times. The internet age ushered in a new culture of aspiring to things that were once frowned upon. A culture that expelled our tendency to cling on to morals. During my final years of high school, an older student walked into my class and invited some of my friends for a conversation. I remember the envy and curiosity that took a hold of me that day and the days that followed, when their conversations turned into them hanging out and leaving me behind. I would later find out that this had been the recruitment ring for the group that would later become internet fraudsters. By the time we became seniors, all the boys in my grade had become part of this scheme.

It was 2005, the early days of the internet in Nigeria, cyber security and monitoring had not yet become a thing. Four hundred years of the Transatlantic Slave Trade was the justification, and the monies made were defined as reparations. These were high school boys, but the idea of getting reparations from the West was always on the tips of their tongues. None of them thought for a second that what they were doing was criminal. It was just a thing any of them could do. By the time we were graduating high school, some of my classmates had become Yahoo Boys, wearing the latest wristwatches, sneakers and the like, all gotten from stealing the credit card information of Americans and Europeans. In the years that followed, while I was struggling to fit-in in my first year of university, I remember coming home to Abeokuta and seeing some of the juniors who were now seniors driving cars their parents could not afford, living lives of affluence and wealth. I was tempted but the mentorship of my sister’s husband held me steady. He reminded me that those whose credit card information was being stolen were people too, just like me. People who were also trying to make sense of a world they didn’t ask to be born into. As the years passed and government legislation against fraud became stricter, a number of these boys either morphed into organized e-crime syndicates or stopped entirely. But one thing is for sure: Yahoo Boys are now so well-distributed around Abeokuta that everybody knows at least one. Our society is rotten in its core, yet we blame the politicians for robbing us blind while we permit crime without a shudder.

*

As I descend the long road of Omida to begin the next leg of my walk, I feel a sharp pain in my chest. It feels as though I have imprisoned something inside my body and it’s trying to escape. I think about the many symptoms of the coronavirus and wonder if chest pain is one of them; and if it is, if I should be worried. There were new coronavirus-related-death numbers on the radio last night, and every day the numbers are turning into names. Last week, it was a prominent politician. This week, the virus has claimed a former beauty queen and a prominent radio talk show host. I find myself thinking about the hundreds whose names I don’t recognize, how the virus is depositing sadness and fear in its wake.

Yet, as I walk through MTD and the gigantic Governor’s Lodge in Isale Igbein, I can’t stop thinking about Richard Dawkin’s opening sentence in Unweaving the Rainbow. “We are all going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones.” Or Albert Camus’s words from his Notebook entries from the year 1951-1955. “It’s not dying that I fear but living in death.” If this is the truth, what then is the purpose of taking care, what is the point of wearing a mask, washing our hands, what is the point of this long walk of mine? What is the purpose of all this attempt at surviving if nature’s debt of death is the lucky way out of this? Of a sudden, the white-browed coucals who have made a home in the trees that surround the Governor’s Lodge break into this deafening racket, as though the sight of me is the most absurd thing. This noise jolts me out of my melancholic hole. But even as I climb from Isale Igbein into Grammar School, I can’t help thinking Dawkins might be right, even though he wrote the book in a different era. Perhaps surviving this pandemic and experiencing the heartaches afresh on the daily is the very worst of this period.

*

The cemetery is always full of chatter, the silence of the dead and the soliloquy of the living. I sometimes wonder what the dead think of the living when we visit them at the cemetery. If they are irritated by the constant babble or if they find the performance calming. An older friend now dead, once asked if I knew why people talk to the grave, I told him I didn’t know. At the time, I could never imagine myself doing it. The idea that someone close to me would die was a thought I never allowed myself to have. But now I know what it means to speak to the grave. To allow words leave your mouth into the air, to believe someone who once was, could take the words and do whatever they felt with them. “It is memory,” the older friend said. When he died years later, I would often think about this conversation. I would think about the line in Louise Gluck’s poem that says, “We look at the world once in childhood. Everything else is memory.” And I will come to my own conclusion that perhaps, in our memories of the old world lies our survival. Perhaps memory is the treasure buried with the dead that we are trying to exhume.

*

As I complete the climb up the hill of Igbein from the Governor’s Lodge, I feel my calves burning and the rest of my body protest. According to the health monitor on my wrist, I have achieved what I set out to achieve with the walk, to double my usual dose. I have walked ten kilometres. But I have not even reached the point from where I will begin the home stretch. I take a moment to catch my breath in front of the uncannily modern 173 years old St. John’s Cathedral in Imo. The structure is an architectural marvel. This is where the legendary linguist Samuel Ajayi Crowther united with his mother after spending about twenty-five years in slavery before eventually becoming a bishop. Sitting in front of the church and remembering Ajayi Crowther, I bring out my phone and scroll through my twitter feed. From the beginning to the end, the conversation cascades between “End Systemic Racism” and “Black Lives Matter.” It seems as though people of colour all over the world have found their voices all of a sudden. Yet another black life has been lost and it is forcing America to have a conversation it would rather not have. So, from social media feeds to the streets, the drums of protest are loud and clear. And like that, the fire ignited by this murder will burn throughout the world.

*

As I begin my walk back home, from Sapon to Itoku towards Totoro, I think again about what it means to survive this pandemic. I think about what it means to me. I am supposed to begin grad school in a few weeks and yet everything looks and feels bleak. There is a sense that the earth has reached its limits, and there is no way out. Some Christian organizations using social media have suddenly forgotten their messages of hope and reverted to the status quo ante. “Repent for the end of the world is near.” A pastor named Oyakhilome is one of the major voices. He insists that the pandemic is connected to the release of the 5G technology which he says is the sign of the Antichrist. His conspiracy theory is taking shape in the hearts of many who have nothing else to hold on to. It all makes me wonder what this world will look like when this is over.

Tolu Daniel is a Nigerian writer and editor. He is a graduate student of English with a concentration in Creative Writing at Kansas State University where he also teaches Expository Writing. His essays and short stories have appeared offline and online. He currently holds editorial positions with both Touchstone Literary Magazine & Panorama Journal of Intelligent Travel.