Are African Writers Ready For Science Fiction?

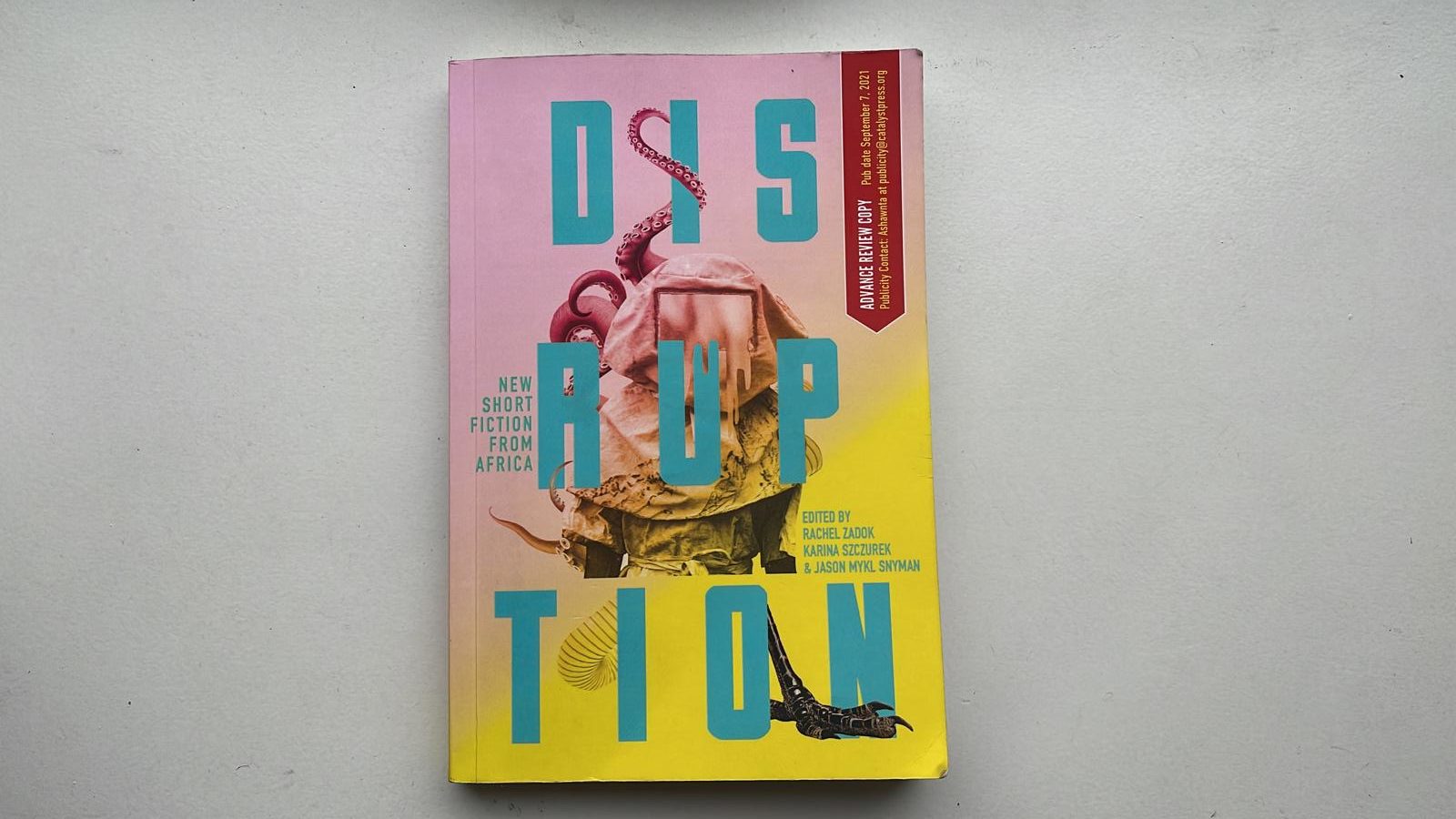

Disruption, the 2021 anthology of Short Story Day Africa, with its themes and carefully chosen title, couldn’t have arrived at a better time. 2021, like the preceding year, will go down in history as one of the weirdest years in humanity — a rather ordinary year disrupted by pandemic and human follies.

With stories from several African countries and themes ranging from love to betrayal, family expectations, capitalism, diversity, famine, migration, and climate change, Disruption is a celebration of new and emerging voices in African literature.

Idza Luhumyo’s “Five Years Next Sunday” which is the winning story of the Short Story Day Africa competition and deserves the prize considering the thematic fabric of the story: a beautiful story of love, betrayal and the age-long myth of rainmakers reimagined in a modern-day setting, Luhumyo’s story is a celebration of the other — queer love, physical difference and supernatural gifts.

In “Five Years Next Sunday”, the 23-year-old protagonist, whose hair has the power of rain, is exploited for personal gains by immediate family members and foreigners. In the end, her decision to cut her hair for her lover, in hope that it will set her free and release the world from drought, ends bitterly for her. Luhumyo employs sublime language and distinctive characters to tell the story of modern-day exploitation. More importantly, the author’s unbending and unapologetic use of code-switching, without resorting to that eye-sore route of explaining either directly or in context what she has written in languages other than English is defiantly brilliant and noteworthy . Luhumyo told an alluring story of love and belonging that could only be told in multiple tongues and she didn’t disappoint on delivering this.

The opening story, “Static” by Alithnayn Abdulkareem explores a post-apocalyptic tale of migration, colonisation and again, the feeling of otherliness. Set in a dystopian community, Eko, a society that hasn’t seen rain for years, this story is plagued by loss and new beginnings. As the people of Eko continue to die due to drought, the protagonist, Amina, is selected due to her “excellent physical and mental assessment scores…to join the new crop of migrants to Planet Forma.” We soon learn that Amina is chosen because she is considered as a “diversity goldmine”. She will leave behind a dead mother cremated in a shallow grave and a lover who refuses to leave the dying city and emigrate with her. The new planet, full of ‘the pale ones’ can easily be seen as a symbol for the western world. Abdulkareem’s play on a dying city and the emigration of the brilliant minds into a different community/planet where they are referred to as ‘the other’ is a sad but familiar tale of present-day Africa and the ongoing and disheartening emigration of brilliant minds from the continent to Canada, the US and European countries. A new wave of colonising Africa — this time by extracting not her natural resources but by mining the talents that could hold the continent up.

However, Abdulkareem’s story offers nothing new or original. His post-apocalyptic society – with its “paleness” and robots – could have been extracted from thousands of post-apocalyptic novels from western writers, and except for the Northern Nigerian and Arabic names of the characters, one wouldn’t have noticed any difference.

Like Abdulkareem’s “Static”, several other stories in the anthology explore the destruction of the world, humanity, and avoidable climate change brought by deliberate actions and man’s foolishness. Innocent Ilo’s ‘Before We Die Unwritten’, set in Bambu Estate, a beautiful riverine community, is an examination of the ecological damage man’s insatiable desire can wreck on humanity.

Also notable among the apocalyptic stories in the anthology is Kevin Mogotsi’s “Objects In the Mirror Are Stranger Than They Appear”. An end-time tale laced with sensual humour but also solemn stories of sexual abuse and loss, Mogotsi’s story raises that one question that the world shies away from — how do we handle sexual assaults of men? Do we just sweep it under the carpet like the protagonist who stands “outside the police station and stare at the entrance for an hour, forty-one minutes and thirty seconds”?

Weaving in and out of the narrator’s mind in a frenzied pace that confuses both the narrator and the readers of what is real and what is imagined, Mogotsi’s story falls short of expectations when the author resorts to some sort of sermon and introspection towards the end. This undoubtedly slows down the pace of the story and tries to force-feed the readers some unnecessary didactic messages.

Kanyinsola Olorunnisola’s “Another Zombie Story” has the best opening in the anthology. “The end of the world doesn’t sound the way you’d think it might. There was no wailing, no screaming, and no howling. The very first time the world ended, it did so in absolute silence, and since we hadn’t really been alerted to that fact, most of us just went about our daily patterns as we always had.” Exhibiting a total departure from the cliches of end-time symbols, Olorunnisola’s story from the very beginning demands that we discard our expectations of what the end of the world will look like. It becomes easy from there on for the author to extricate us from our boring life and immerse us in this imagined world of orisas, Pharaohs and creatures “from the Ossident”. Olorunnisola’s story, unlike the title, is not just another zombie story.

Sadly, not all the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic tales in this anthology demonstrate the expertise and illusion expected of this genre. Most of the stories in this anthology still rely heavily on western cliches of what end time will look like. Almost every story about the end of the world here borrows from American dystopian and apocalypse events and biblical symbols of end time — with drought leading the pack of what we are to expect when the world crumbles, and machines and robots coming closely behind. By the fifth or sixth story of drought and doom in this anthology, the reader is thirsty for a new kind of disruption that doesn’t dehydrate the brain and soul.

Although science fiction is still a white-dominated genre, Black sci-fi has come far from the days of zombies, aliens and white-washed robots. We have seen how much culture and history can be woven into technology to birth Afrofuturism. Writers like Suyi Davies Okungbowa have built characters and worlds totally removed from European and American mythologies. It’s been done; it can be done. More than any other genre of fiction, African sci-fi is ready to stop paying obeisance to the West. Therefore, to read apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic stories after stories borrowing that eye-rolling symbols of white-version of the future, to find stories that lack identity save for that borrowed from the West, show a lack of originality and vivid imagination expected of writers of that genre and it brings back to mind that 2009 question by fantasy writer Nnnedi Okorafor — Is Africa ready for science fiction? This time though, one wonders if the next generation of African writers writing science fiction set on the continent is ready to divest itself of Western influences, fully decolonize the genre and produce a new archive.

There is no doubt that Short Story Day Africa is doing a fantastic job of nurturing and presenting emerging African writers to the world and they deserve the accolades. However, with this anthology, perhaps less could have been more for SSDA. While these are stories from emerging writers, and perfection -fickle and non-existent as it is- should not be expected, some of these stories fail to believably transform the readers into their imagined future/world. There are stories in this anthology that would have benefited from a few more drafts and the authors spending more time with them instead of finding a hasty and permanent home in an anthology that is supposed to showcase the best of a new crop of writers on a continent as talented as Africa.

Adeola Opeyemi is a writer and developmental editor. A fellow of the Ebedi International Writers Residency, she was shortlisted for the 2019 Morland Writing Scholarship and the 2015 Writivism Short Story Prize. She is a 2020 Miles Morland Scholar at the University of East Anglia.