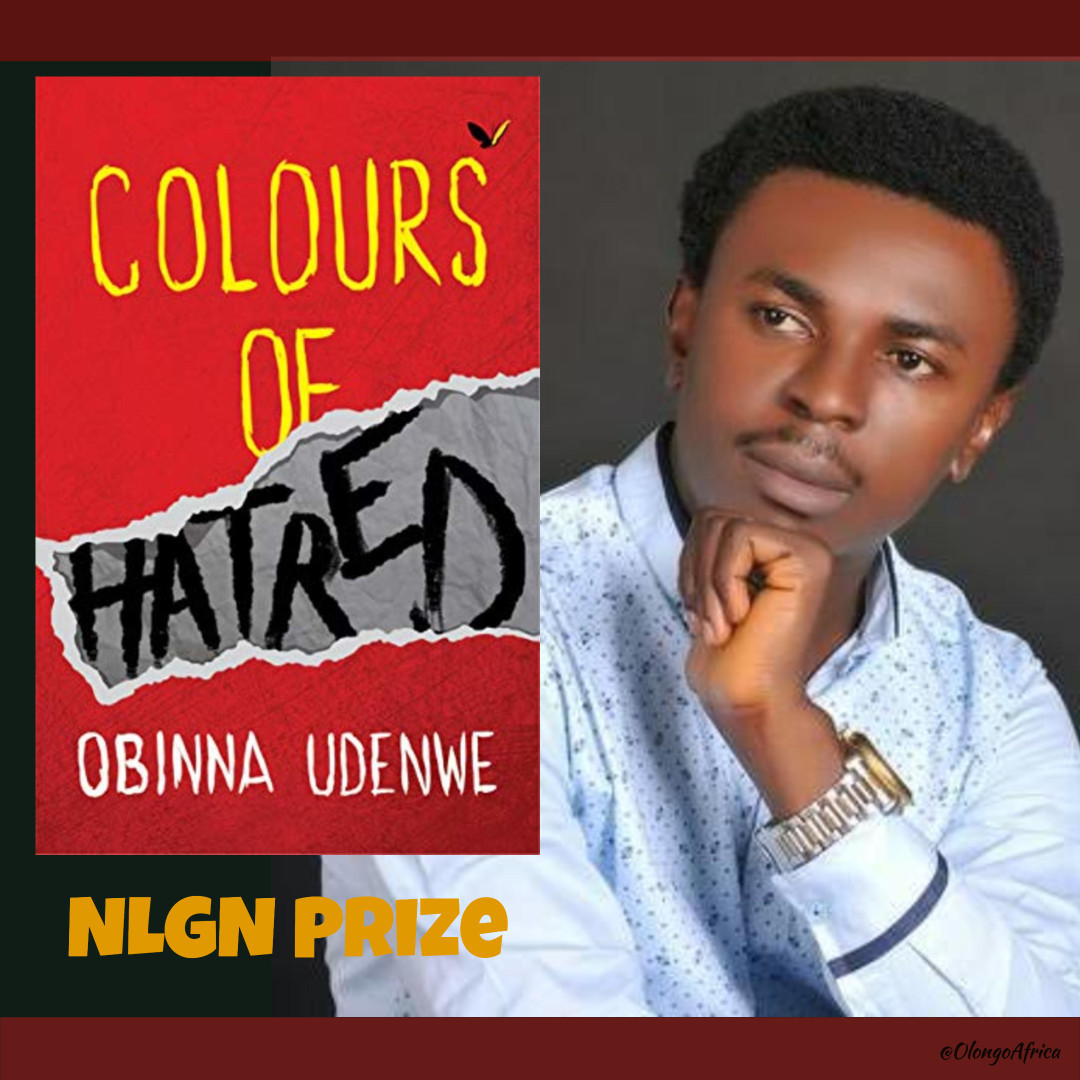

Hatred of Many Colours

Colours of Hatred is a riveting narrative, coordinating language beautifully and weaving a fine web of intricacies through the different characters Obinna Udenwe presents before us. It could be suggested that Obinna had a fine story and employed characters to help him execute the job and sometimes those characters’ place in the story could be questioned.

In Leona Egbufor, Obinna Udenwe created a stunning but troubled character whose afflictions began innocently as a child observing her maternal grandfather become tough and defeated, and it matured into grave psychological trauma that became love for family and her eventual downfall, even though some of these information appeared late in the novel.

Colours of Hatred is undergirded through bildungsroman. The protagonist’s life is then a result of society’s many complexities such as war, tribal differences and politics, parental urges – direct and indirect, and her infantile tendencies that could be hidden in blind love for James or Mary – her parents, and her inability to question things independently and be inquisitive enough to take calculated steps devoid of ramblings.

Obinna, like Nnmadi Oguike, has created such a beautiful family narrative with commendable efforts in research and blending two different cultures, of Sudan and Nigeria in a narrative about hate and lust, war and escapes, attention deficiency and patriarchy, greed and exploitations.

In Nnamdi Oguike’s short story, ‘Camp in Blikkiesdorp’, he explores the subject of decrepit spatiality within the South African context of slum. The narrative is drawn on with the strokes of realism and one could be convinced that he had lived there when in reality he hadn’t. Same amount of work that aids believability accompanies Udenwe’s effort, he blends fact and fiction almost seamlessly in Colours of Hatred, so much you would be tricked to believe that somehow, these events were connected. The story is built in such a way that you can follow the lives of the characters from when it began in Sudan and how they evolved into all that would win them the world and eventually destroy them.

Colours of Hatred brings a human face to mental health issues and suggests likely unconventional sources that are often ignored as causes. Udenwe portrays this and de-emphasizes the boundaries of economy. For example, he proposes to us that both beautiful and rich people could be afflicted by this. All we see and participate from close or far quarters sum up for the total unit of our consciousness and somehow, when lied to with some facts like James to Leona, we can become more than just tools for people. We become beasts but in all of these things, we do not know, because our lives are normal, we see those we love and we sneak out to be silly with our lovers and friends but as the day goes by, we sink steadily into all that we have been designed to become, by society’s many flaws and when we manifest, people are shocked. A secondary school teacher having sex with a student could be responsible for such young girl who caught them to grow into dating a seminarian without remorse.

Unstable leadership in African countries hasn’t just ruined family lives, it has fried the mental house of men and women whose talents and skills could have built a thriving society. And because we only protect our families, like Grandpa in the story, when the ripple effect comes, all the money saved does not take away the pains, it heightens it so that the tragedy has a finer class than that of the ordinary people on the street. Leona could have escaped Sudan but the effect of the war and Grandpa’s politics trailed her.

Udenwe is consistent in his presentation of conscious details and an easy flow of narrative in Colours of Hatred. Yet, the juvenile expressive nature of Leona could be depressing. Maybe this is because the first person narrative technique helps greatly, but maybe because the writer wanted us to see beauty and vulnerability in the same character and lots of talks.

Fact and fiction – faction, is a brilliant way to affix new ideas around history. And Obinna’s effort paid off since anyone who is conversant with the history of both Sudan and Nigeria could easily relate to what transpired and what politics and lust, ambition and personal insecurities can lead people into.

Literary critics from Africa usually frown at direct interpretation of terms and expressions of indigenous expressions in narratives from Africa in the text, tying it to the inferiority complex suffered by African writers but Udenwe handled it beautifully, so that he translated what was necessary and left the rest for the reader and researcher to take a crash course in Igbo language to follow the expressions.

As noted earlier, Leona’s self-appraisal of her own beauty became a bit disturbing at some point – how could we have known she was stunning without her telling us these things? What kind of mind extols her own beauty beyond normalcy? Why that could be credited to her deteriorating mental health as seen in the prologue, the narrative style did not acknowledge her breakdown of health and her difficulties as suggested in her dying nature. We still see a narrative that is as smooth as when she was well. And again, what sort of highly protected businessman gets stabbed in his well secured house yet his guards could not be alert to hear him scream and come to his aid especially when he was still unsure of Leona’s intent? And dogs kept barking! What happened to blood trails?

There were interjections that were thrown into the stories without necessary foreshadowing if they would ever be needed or they were just decorations. Agnes had a tortoise. And that information came in the middle of a narrative yet we had been introduced to this character but we never truly saw what she owned and what her properties foreshadowed about her personality and even what became of her arch.

Obinna’s story would make for an interesting movie, especially the melodrama at the bedroom with Akinola’s father who was summarily described as weak and Leona whose physical strength had not been revealed anywhere in the story is made to attempt murder and carry out such act as taking a fat-wheelchair bound potbellied man from ground floor to his room upstairs without waking anyone in the house yet the dogs barked without ceasing.

Sometimes it feels the characters were just given roles solely to push the story forward and not for what they had been built to convey. But the beautiful writing, the diction often masks these concerns. Onyinye’s physical assault on Agnes came as one of those surprises. Has there been some hatred or conflict between these two that heightened at this stage or the writer needed some action? And when Akinola started his love project, it read like Christian Grey’s character in Fifty Shades of Grey.

Obinna Udenwe in Colours of Hatred successfully created a beautiful character whose praises for her own beauty became almost depressing and whose mental health we learned, with time, deteriorated because of accumulated information and experiences, showing us how toxicity rises. But if the writer has to get applause, it would be for how he was able to marry the history of two nations in Africa with commendable details. Colours of Hatred is a birth of flaws of man in a giant web, of a man avenging the disrespect shown to him by a contemporary who imprisoned him and blackmailed his wife, of a daughter who must be used to avenge these things, and of young women finding salvation in rich married men. Colours of Hatred is a gritty tale.

Bura-Bari Nwilo writes from Nsukka in Nigeria. He is originally from Ogoni in Rivers State. Fiction and photography excite him. He is the author of The Colour of a Thing Believed, a book of short stories.