What Exactly Do You Want to Know in Tolu Agbelusi’s ‘Locating Strongwoman’

In Tolu Agbelusi’s first poetry collection, Locating Strongwoman, there’s a poem titled “Museum of Women,” that acknowledges and celebrates the various ways women have affected the growth of the speaker and her ongoing construction of womanhood and selfhood. The poem uses the museum as an austere aide-mémoire of women’s lived experiences, the shifting between dispossession, the accomplishments, and rumbling stories of violence, performed resiliently well, to become a resource for others. As in the museum, there are many hidden stories of women that we don’t even know about until we are told or make the effort to dig. I found “Museum” an appropriate nodal point to begin my review of the complexities of black womanhood and the myth of female endurance, which is a recurring theme in Locating Strongwoman, because it captures how for many women, attaining womanhood is also about learning to read and learn from the silence of others. Like the museum, we do not know the stories of the objects that we come across until someone tells us, or we excavate them.

The poems in Tolu Agbelusi’s collection confront the sociality of black women and the many ways violence against black women is unspoken. Locating Strongwoman invokes an intimacy that is usually found in the convergence of women recounting their personal stories. Agbelusi’s poetry collection succeeds in its ability to elicit sympathy for women’s suffering and the shared burden, especially of Black womanhood. She writes about the broken woman, the little-joy woman, the helpless woman, the girl-woman, and the torn woman, all of them, devices of a ploy that has them sworn to silence, even so much that the dream for contentment is a call for caution: “Does it matter if I am always escaping? /If I can’t let myself be carefree?” a speaker in the collection asks . The point is, we are not unfamiliar with the situation represented in this volume because we always meet female characters displaying a stoic acceptance of their suffering. However, our expectations for socially acceptable behavior mean that women sometimes have to hide their problems and hold up a positive, inspirational façade for others to admire. Perhaps this sense of learning to invest the pain into something influenced the ideas for the two poems “Locating Strongwoman” and “Strongwoman”.

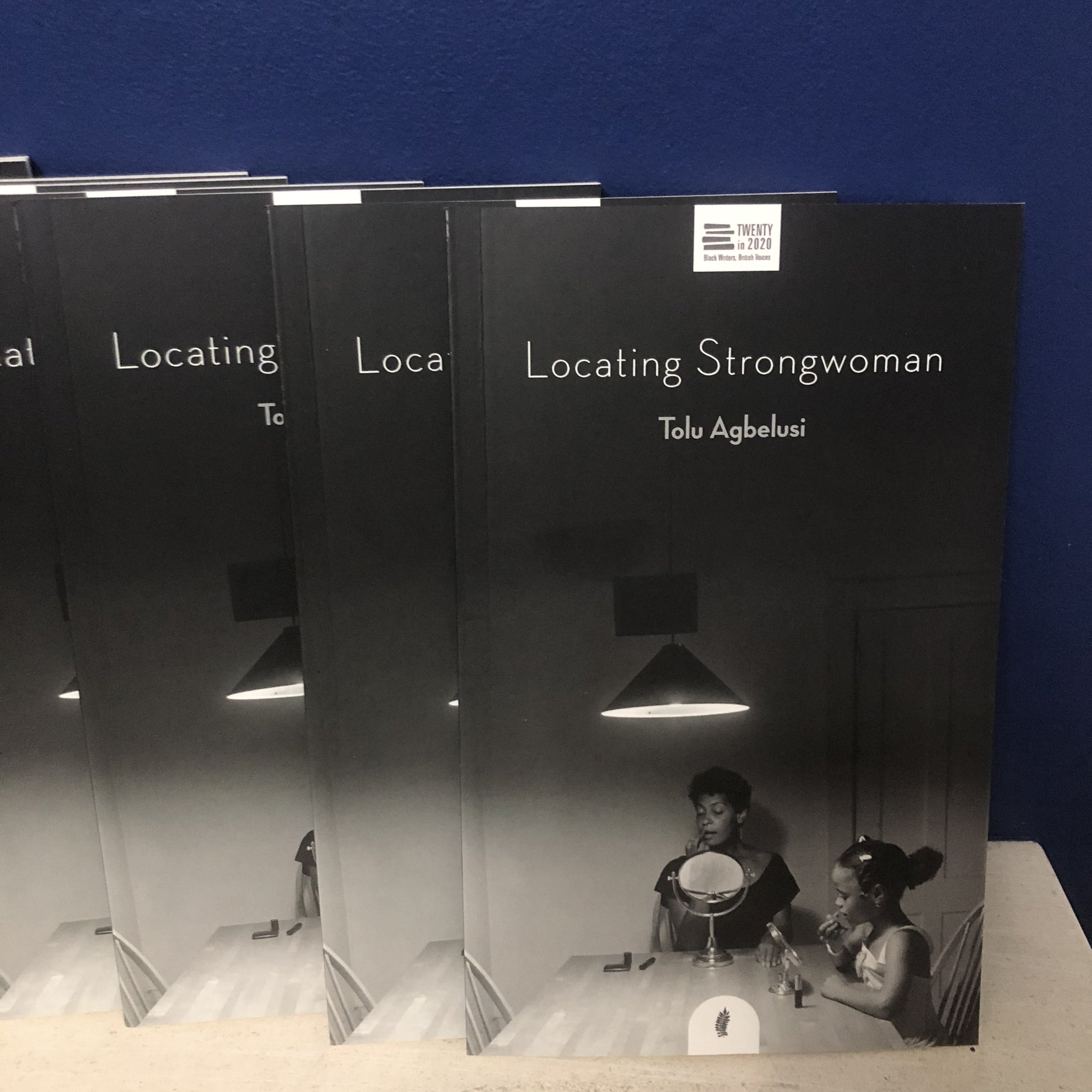

In “Locating Strongwoman,” after Carrie Mae Weem’s Kitchen Series, Agbelusi uses the mirror as a symbol for comparing and documenting the experiences of a daughter and her mother, beyond physical appearances. The chord that this poem strikes in the reader is that it reflects the intangible substance that holds the relationship of black women from one generation to the next: “Hands placed just so, I instructed the mirror to document transformation—becoming my mother with nothing more than a gesture and the sheen of bright red gloss.” This experiential transitions through the mirror, are tender as they are austere. The power of the mirror as a forensic evidence of the past is again used as a motif in the poems, “She wears Beauty as Costume. Happiness Too,” and “Belle”. In these two poems, the mirror re-imagines how negligible physical resemblance becomes, as one considers the responsibility to exercise strength, while struggling with self-doubt and violence. On the one hand, the impression I get as a reader is that the decision to be visible but still silent is embodied in the act of black womanhood, so much so that what can be considered a distressing situation is valued as strength. But this power, like Agbelusi, helps us to see in these poems, is a constant mental assault shared by many women. These poems are moments of women’s life struggles that are translated into fleeting days of frustration from which everyday relationships with others are transacted. Importantly, Tolu Agbelusi’s poems are stories that examine the thin line between the labor of love and sorrow and the inability of a woman to recognize and express her burden. In the poem, “Things I can’t Say II,” the persona intones the agony of a woman with no voice:

How do you explain that your body must be forced to expel all its air, to let go, that you are too accustomed to leaning on solid things […]

In the poem, “Strongwoman,” the poet shows us that being strong could also mean breaking free from a past that encouraged a lack of resistance:

When a random stranger stroked my car door all familiar, sliding himself into my back seat without invitation or introduction, I hurled my voice: get out! Get out! GET OUT! I hit on third try.

Apart from alluding to the entitlement of others to the body of a black woman, the pent-up and unexpressed frustration in this poem is shedding the old skins of a few years of abuse and silence. Agbelusi’s choice to separate “I Hit” after different variations of the italic font depicts a tense situation that underlines the violence that accompanies the suppressed emotion and captures the decision to break out of the silence of the generation, as she describes in the poem, “Soldier Ants”, as she describes in the poem, “Soldier Ants”. The intensity of an invasion of the memory is juxtaposed with an ant invasion that happened when the speaker was eight: …my white sheets blackened/with their oversized heads. Thousands/of them matted in a black cloud, /clamping into my skin—/a gradual, constant burning. As an adult, the assault continues as the speaker navigates life, repressing the paths of affliction by reproducing the experiences of women before her.

One of the key successes of Locating Strongwoman is to be a witness to the experiences of Black women as they struggle to discover themselves in a world that fails to see their struggle. The poet is a witness, and she wants the reader to also see what she has experienced. This need to be emphatic, when she needs to, like someone assuming a role that she has been denied, accounts for the frequent use of italics throughout the collection. The structure of the poems is often almost invented and determined by the subject being treated: crossing out words and emphasizing presence and affirming hope through the use of italics.

In a rather affective tone, Agbelusi returns us to Boko Haram’s brutal attacks on Baga in 2015, where the victims of that massacre were mostly women, children and the elderly. She reminds us of how the traumatic event became a turning point from which lives were recast. In the “Before the Bomb Blast…(Baga Massacres 2015),” a young girl who is considered a tomboy links the days she receives the gift of a girly bag from her dad just as they receive the news of the Baga attack. The trope of the tomboy used in this poem reflects the middle class, and how gender roles are in continuous conflict. By placing violence in Baga with a middle-class girl in another climate, contemplating an objection to her body, is a reminder of the many ways in which pain as an identity for women intersects. Agbelusi is most experimental with form in this poem, as if the reader should understand the intensity of the emotions conveyed and the haunting confusion that results from confronting why concern is always about the female body rather than the many violence against it.

“Ezekiel 37,” one of my favorite poems from the collection, draws connections between the prophecies of Ezekiel and how women can be revitalized. In the poem, the acknowledgement of the woman’s existence is an act of self-expression. The poem does not just focus on physical violence against women, but also on how psychological influences can be invisible unless the intimate bond between women makes a sister’s pain visible:

If I’m lucky, a sister will smile arms around Me on my commute, hold my gaze Long enough to make certain I feel seen[...]

Essentially, the story here is that women of color see each other.

The poem concludes with a contemplative thesis reflecting the entirety of the different voices in the book, which is the hope to break free from the code of silence. The speaker breaks free and decides to speak the words that those before her could not speak.

wholeness will find its way back to your breath whatever is broken in you will heal, you will remember who you are, until then, you will not. carry your bones alone.

In the Cento poem, a 38-year-old who has found the words to contemplate her existence and reinvent the wheel that had stifled her being is the speaker in this poem. A cento is not just a form in this collection, it also becomes a way to reinstate presence in a collection that digs out the stories that fill up women’s silence. Agbelusi begins with a line from “Rembrandt’s Late Self-Portraits” by Elizabeth Jenning: “You are faced with yourself” to move on to a host of other equally brilliant poets, such as Rainer Rilke and Jack Mapanje.

I had not expected to be an ordinary woman, plain as bread. Silence arrives like a servant to tidy things up […]

The question of being considered inadequate drives the speaker into silence, which allows them to rediscover what was lost. As in most of the poems in the book, the poet is discovering herself, and in the process finding her voice through the words of others.

Locating Strongwoman is important, precisely because of its ability to locate those small places where women tuck their emotions, which essentially shows that there is no neutrality in women’s lives, only vague stories of entanglements and complications. Although the experiences shared in the book is essentially that of black women, the book captures the universal matter of shifting selfhoods that women face.

And when I succumb, gripping the iron, the cloth, the hope bound in the motion of a hand passing heat left to right over a crease, willing it to disappear as proof that the dishevelled can be smoothed again, what is it it not prayer?

As the poems in the collection shows, Agbelusi displays a strong understanding of the complications of existing as many different things. To be a strongwoman is to be someone who remains strong despite the everyday chaos, finding comfort only in hoping to be seen, until she realises that she can resist:

Painting a small room anything but white Invites a grim darkness—carob hued […]

To return to the motif of the museum which I began this review with, women are exhibits on display. Agbelusi shows how the stories of these women are not only installed into everyday life, but also are still unseen. It is for this that as Audre Lorde once reminded us, “poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.” Agbelusi’s collection of poems breaks the silence; there is something to know about women. Black women.

Jumoke Verissimo is an award-winning poet and novelist. Her latest work is a novel, A Small Silence.