Sóyínká Off Broadway: Swamps and Syntheses

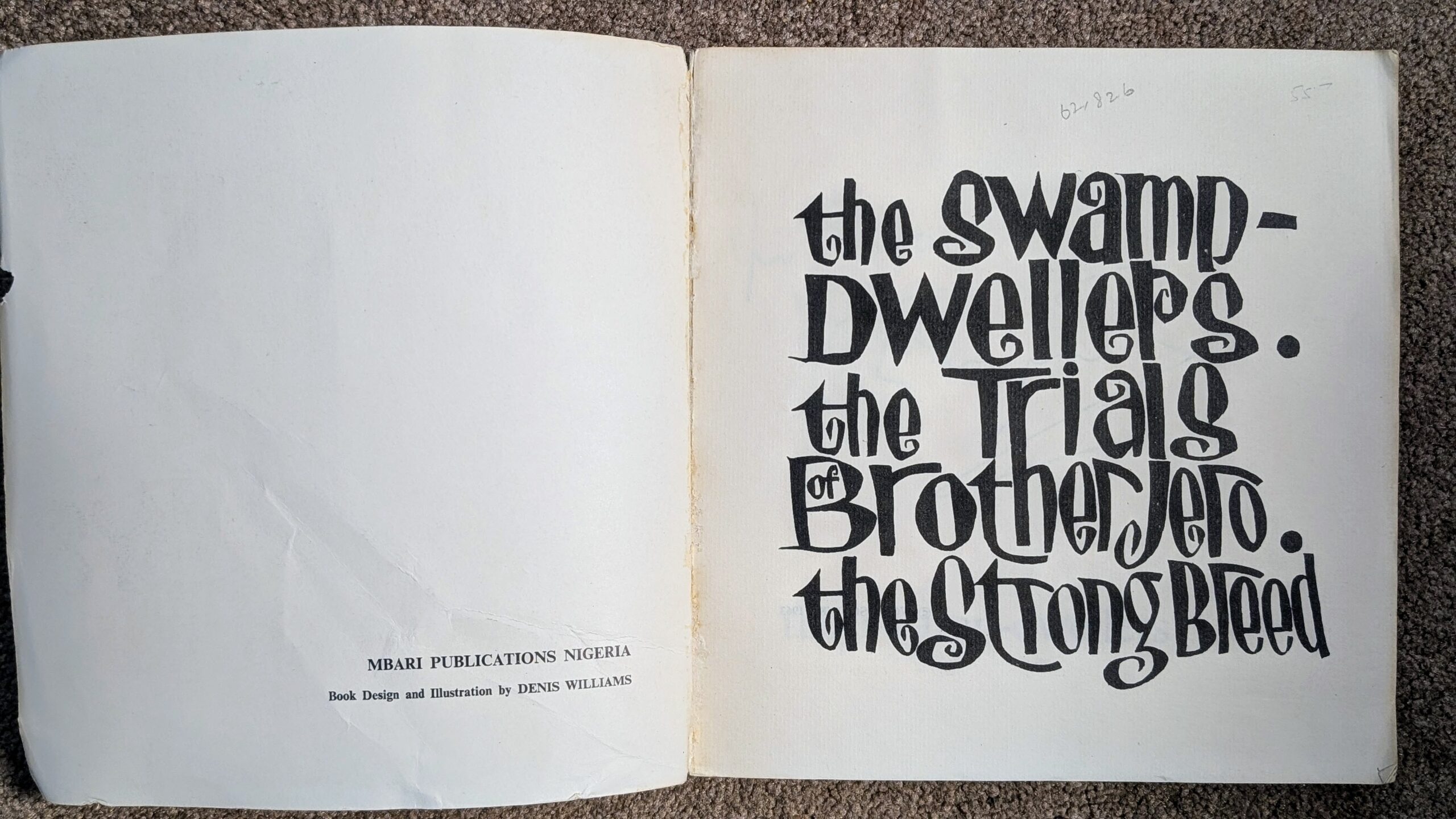

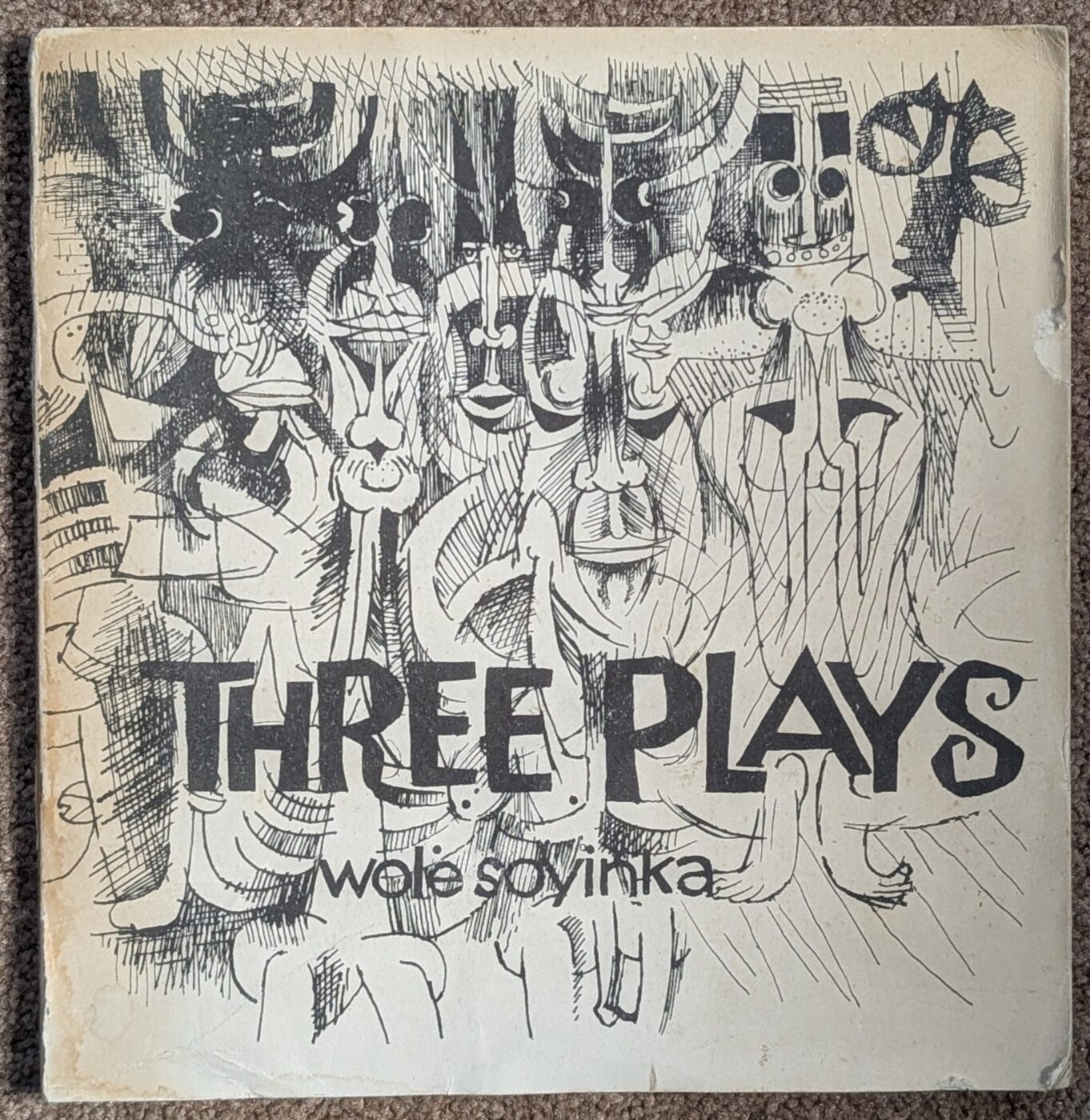

The off-Broadway premiere of Wole Soyinka’s 1958 play, The Swamp Dwellers, offers at least two reasons to be excited, and hopeful. The first comes from a point that is almost over-made in the American media, with theatre critics describing the event as some sort of lost-and-found moment. The New York Times reported the playwright himself as saying he had “forgotten the existence” of the play. Others highlight Soyinka’s relative youth—circa 24—when he wrote this play with themes that have only become even more relevant over the last sixty years.

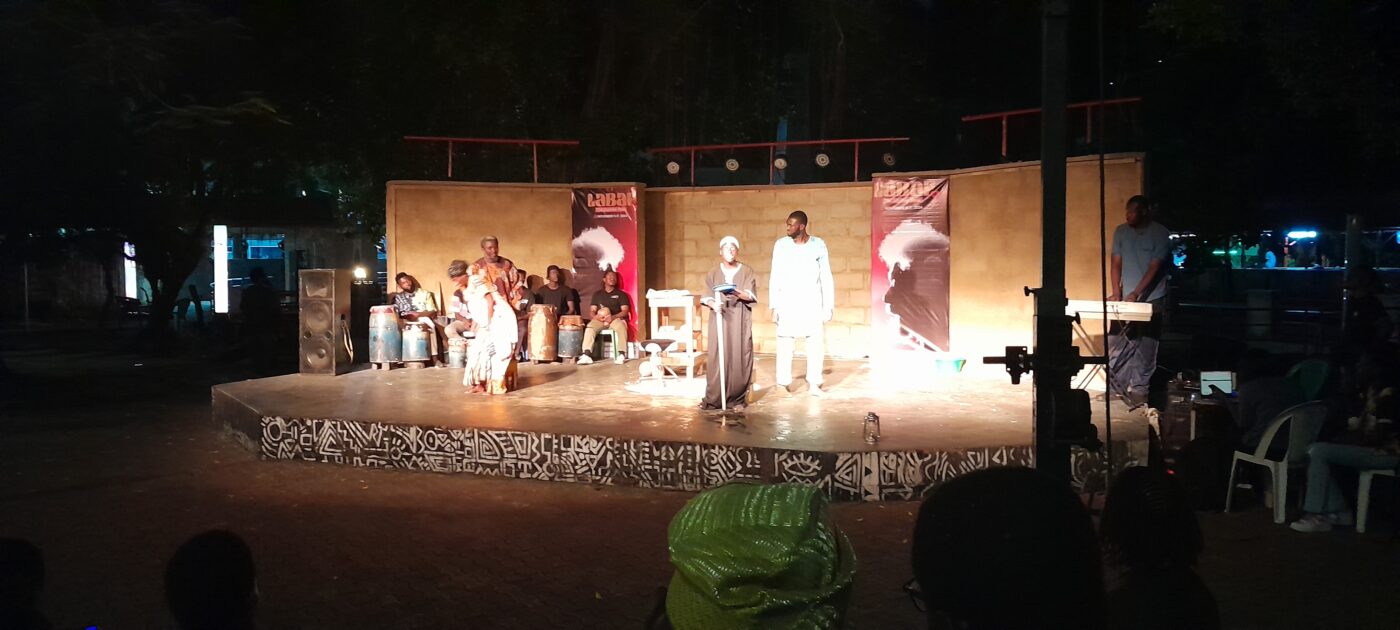

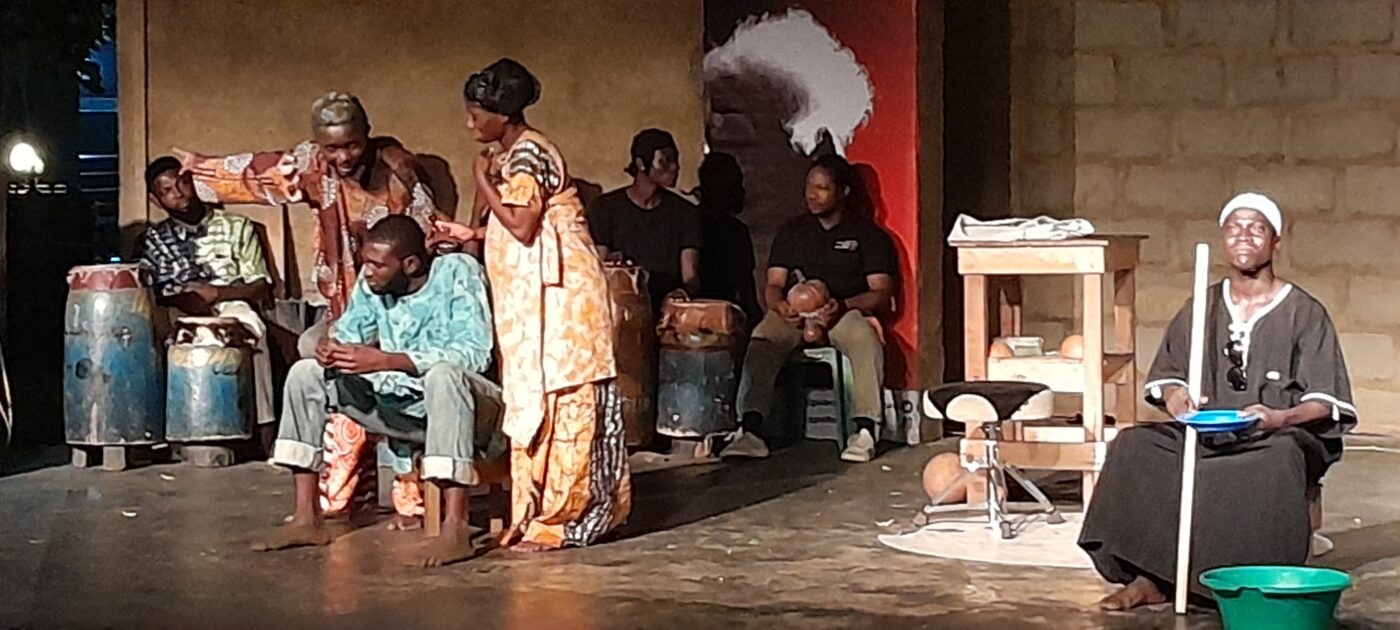

The truth is that The Swamp Dwellers has been performed in Nigeria on occasion. I vividly remember a Nick Monu-directed production in the late 2000s at the Wole Soyinka Theatre in Lagos, featuring standout performances by Albert Akaeze (Beggar), Toritseju Ejoh (Igwezu), Martins Iwuagwu (Kadiye), and the recently deceased Wale Macauley (Makuri). More recently, Segun Adefila directed a Crown Troupe performance of the play for the 2024 Lagos Book and Art Festival at Freedom Park’s amphitheatre. On a personal note, The Swamp Dwellers inspired my own play, The Botching of a Brute, written originally for radio in 1996 and later adapted to stage. The same Adefila has directed it twice—in 2002 and 2006.

The ‘lost-and-found’ messaging is understandable, though, given the traditionally uneven attention to Soyinka’s broader works. Theatre producers, as tastemakers, naturally curate selectively, but the neglect of Soyinka’s lesser-known plays goes beyond the call of critical discrimination. Academic theatre that should be a lot more explorative has not been spared this tendency to stay with the familiar, and the safe. As I noted on X.com in my initial reaction to this American production, “The captive ‘big’ plays have usually denied the world of the vast pleasures of Soyinka’s diverse theatre-verse.”

Beyond well-known works like Death and the King’s Horseman, The Lion and the Jewel, and Kongi’s Harvest, Soyinka’s oeuvre includes plays like A Dance of the Forests, The Strong Breed, and Camwood on the Leaves, all rich with themes that should be explored. Issues like disability, ostracism, and child abuse in The Strong Breed, or generational rebellion—what I once called Okonkwo Complex—and a return to African spirituality in Camwood on the Leaves, grow ever more resonant. The Swamp Dwellers itself tackles environmental damage and climate change, themes that feel increasingly urgent today.

A second cause for optimism about this ‘revival’ is the opportunity it provides to spotlight overlooked issues. While the production’s official play description stresses the familiar trope of Yoruba mythology, hardly setting store by its Niger Delta setting, theatre reviewers seem to be getting its ecological messages. Loren Noveck of Exeunt NYC described its “sense of climate apocalypse,” and BK Reader highlighted its critique of the environmental and social costs of wealth inequality. By choosing an old play with such pressing themes, this production may draw global theatre’s attention to the neglected issues of Nigeria’s delta.

Indeed, the ecological themes of The Swamp Dwellers were never quite hidden. In 2009, Adrian Ivakhiv reported it being suggested as one the works to consider for correcting the dedicatedly white, male and American canon of environmental studies that was proposed as the field began to take shape. When, in 2018, I began seriously researching ecocriticism for a conference paper, the narrowness of its canon was still notable. Think about the signal absence of Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre, perhaps Africa’s leading poet of ecological imagination, in the scholarships of ISLE, the field’s prime journal. The situation remains the same, even today, if the contents of leading handbooks and readers on the subject is anything to go by. Yet, if we take the publication of the collection The Eye of the Earth (1986) as a marker, the full ecological turn in Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s poetry is roughly contemporaneous with the beginnings of ecocriticism as a serious field of study. Since that time, the field has healed itself of the initial resistance to works of imagination, but obviously not so much to works of an African ecological imaginer.

Scholars are often upfront about ecocriticism’s other struggles, like its theoretical incoherence, and its limited real-world impact. Latter-wave ecocritical schools like posthumanism and new materialisms which seek to de-centre humans and create a “democracy of objects” have, for example, come to unresolved tensions with emerging, human-focused environmental justice theories. In short, have we reached an impasse in an era both critical of anthropocentrism and demanding cultural reform? Could expanding ecocriticism’s mainstream canon help address a challenge of this nature?

Having returned to Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s poetry and ecological thoughts in the last few years, I am struck by some possibilities. There could be alternatives, for example, to the current centric models of discourse in the field—anthropocentric vs. ecocentric vs. sociocentric. Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s poetry provides us with a new geometry—I have called it triaxiality, borrowing from earth and material sciences, and sticking with the metaphor of ‘force’ which is rife in the field—in which human and nonhuman agents are understood in terms of their respective and relative immanent forces, in the manner they behave autonomously and in relation to one another, and the complexities which a third element, social hierarchies, brings into their interactions. In this framing, human agency can be understood, not in its centeredness, or necessary superiority, but by its specific attributes and modes in natural and social settings. This unique flavour—what we may term aegis—is rooted in human cultural capacity, which has driven ecological destruction since the Anthropocene, and must now be actuated for remediation, if there is to be any.

New materialists argue that, as actants, nonhuman ‘things’ have agency. Nonetheless, humans can render them tools—automata. Similarly, social hierarchies can produce socioeconomic factors which, through policy intentionality, or neglect, render marginalised people uniquely vulnerable to natural forces and sapped of will to act for their own reasonable sustenance, or for the exercise of aegis towards the larger ecology. The triaxial model affords us a way to pursue discourses of force asymmetry in nature-engaging and social settings in a manner that treats those facets as a continuum, rather than in which one—the ecological—becomes a mere metaphor for the other—the social—thus bypassing charges of sneaky anthropocentrism. In that sense, it provides us a framework that is both insight-yielding and potentially action-orienting. We can then imagine how much Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s critiques of colonial distortions of land use and food systems can contribute to a field like Planetary Health that is concerned about the dysbiotic implications of these factors.

To return to The Swamp Dwellers with these insights, we may start by understanding the background to the play. An agrarian community in the delta faces environmental disasters in an unusual flood that has left their crops rotting under the swollen swamps. What can be regarded as an ordinary cyclic event takes the shape of oppression when you throw in a factor of a peculiar spectre, a sacred serpent that must be propitiated to gain favours and take control over the forces of nature. The mediator in that arrangement is Kadiye, the taxing priest who seems naturally able to explain away the failure of previous offerings while pressing the locals still to their sacred duties or, all things considered, ransom.

The real actions of the play are enacted in the living quarters of a poor old barber and his family. Their son, Igwezu, has returned from the city to meet the village’s slow ruination in spite of him sending funds to propitiate the sacred serpent. The highlight of the play is the confrontation he has with Kadiye who is visiting the family as usual for a gratuitous offer of drink and grooming services, and perhaps to shake down the just-returned. Igwezu has other ideas, which turn out to be subversive. Could he have merely acquired the general world-wise ways in the city? Or perhaps, his specific experience of the city—his very own twin brother, who preceded him to the city, having possibly cuckolded him—could have severed his ties to village sentimentalities. Or, he could have been emboldened by a travelling beggar who chances upon the home at this opportune moment, bearing a near-heretic scheme to reclaim the soil from the floods by practical means in suggestive hints to regain agency. That very moment—when Iqwezu has Kadiye’s cream-lathered throat at the very edge of his razor—holds both dramatic and symbolic imports. There are those searching questions that the old priest must be careful in answering at the risk of suffering a wrong flick of the blade. And then, there is a certain signification in wielding the tool of human culture—the razor blade—against untamed nature—the priest’s unkempt beard.

African literature has never wanted for unreconstructed enchantment of natural phenomena. Mother-figure imaginings of rivers, cowering at thunderstorms, and rolling over to make way for streams formed from rainfall invading the home, are the staple of poets of a generation. In his literary and life choices, however, Soyinka has bucked that trend. While his dedication to nature, especially forested environments, is notable, he is equally notorious for his commitment to the human will to act. Writing for New York Times following the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, the playwright noted the disparity between the responses of western authorities to that incident, and the more long-standing oil pollution in the Niger Delta. As he acknowledged in that essay, while writing The Swamp Dwellers had been triggered by the discovery of commercial-scale oil in Nigeria’s delta in 1958, it was a broader “compulsive dialogue with nature” that powered his imagination through the writing process. He noted further: “The economic consequences, the impacts of global scramble for wealth, hovered only dimly in the background.”

However, thirty-seven years later, Soyinka would have to campaign—unsuccessfully, as it turned out—to save his compatriot and fellow writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and other environmental and indigenous rights activists from the gallows of Nigeria’s military junta. Regardless of the intermission between the writing of his play and that grisly fruition of oil exploration in the delta, the acute imagining of the character Kadiye shows that it was not really difficult to foreshadow elite complicity in the crisis. Colluding elites have historically been cast and crew in the succession of exploitative global trades in the Gulf of Guinea, one only needs to recall the supercargoes and local merchant princes in the older slave and palm oil trades that went on in the region some centuries before.

In the last few years, Nigeria’s delta has not been as top-of-mind in global news as it was thirty years ago. One hopes that the subtexts of the interplay of natural forces and the complexities of human agency will be clear to audiences who go to see The Swamp Dwellers in its current New York run. It should be approved, even, that the messaging of ‘rediscovery’ enables these insights. There is even more to be hoped for. Taking a book from Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s poetic framings, whatever renewed attention that the play may inspire regarding the Niger Delta could be saved from being side-tracked in anthropocentric debates.

Note: The Swamp Dwellers, directed by Awoye Timpo, runs from 15-27 April 2025, as part of the ‘Theatre for a New Audience’ project at Polonsky Shakespeare Center, New York.

___

Dèjì Tóyè is currently writing a book on the potentially revitalising contributions of the poetry and the thoughts of Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre to ecocritical theory.