The New York Black and African Literature Festival aims to be a bridge | Conversation with Efe Paul Azino

Efe Paul Azino is the Director of the Lagos International Poetry Festival, now in its tenth year. He is a spoken-word poet and writer. He is also the founder of a new literature festival based in New York City. In this conversation, we discuss the new New York Black & African Literature Festival happening between September 5 and 8, its goals and ambitions, and Azino’s work as a poet and custodian of culture.

This interview, first published on FlamingHydra on August 27, 2025, has been edited for brevity and clarity.

***

Tell me the inspiration behind the New York Black & African Literature Festival, and what you’re trying to achieve with it?

The Festival grew out of a conviction that the cultural and political conversations linking continental Africa and its global diasporas need intentional spaces to flourish. While there are many points of contact, those exchanges are often fragmented, shaped by uneven access, structural inequities, and a global cultural economy that still privileges certain narratives over others. New York, with its layered history as a site of arrival, exile, and reinvention, felt like the right place to create such a space. The New York Black and African Literature Festival aims to be a bridge connecting writers, poets, and thinkers from across the Black world, one that expands the circulation of African and diasporic literary and cultural production, and creates a meeting ground for ideas, solidarities, and collaborations that outlast the festival itself.

How does the Festival fit into current conversations in the age of Trump, amid worries about funding for the arts, and about freedom of speech, taking place in a world in chaos?

Literature, culture, and festivals, by extension, have historically provided a form of civic infrastructure where dissent can be spoken and visions for a more just world can be shaped. And so the festival presents, in this moment of democratic backsliding, elite capitulation, and retrogressive culture wars, a space to face these crises with honesty and imagination. Through panels, performances, and workshops, we’re convening voices that challenge censorship, resist cultural erasure, and articulate political and artistic possibilities that push against the narrowing of public life. We are creating a space for safeguarding the imaginative commons.

What artists/writers are you inviting to the festival, and what informs their selection?

We’re curating across genres, generations, and geographies—novelists, poets, playwrights, journalists, scholars, and hybrid artists whose works engage with the Black experience in expansive, often unexpected ways. Guest selection is guided by a few principles: the quality and originality of the work; its ability to speak across borders and disciplines; and its potential to spark meaningful dialogue on the pressing questions facing Black communities globally. We want a mix of the established and the emerging, the canonical and the disruptive.

Can you mention a few of these guests, and what you hope they will bring to this maiden event?

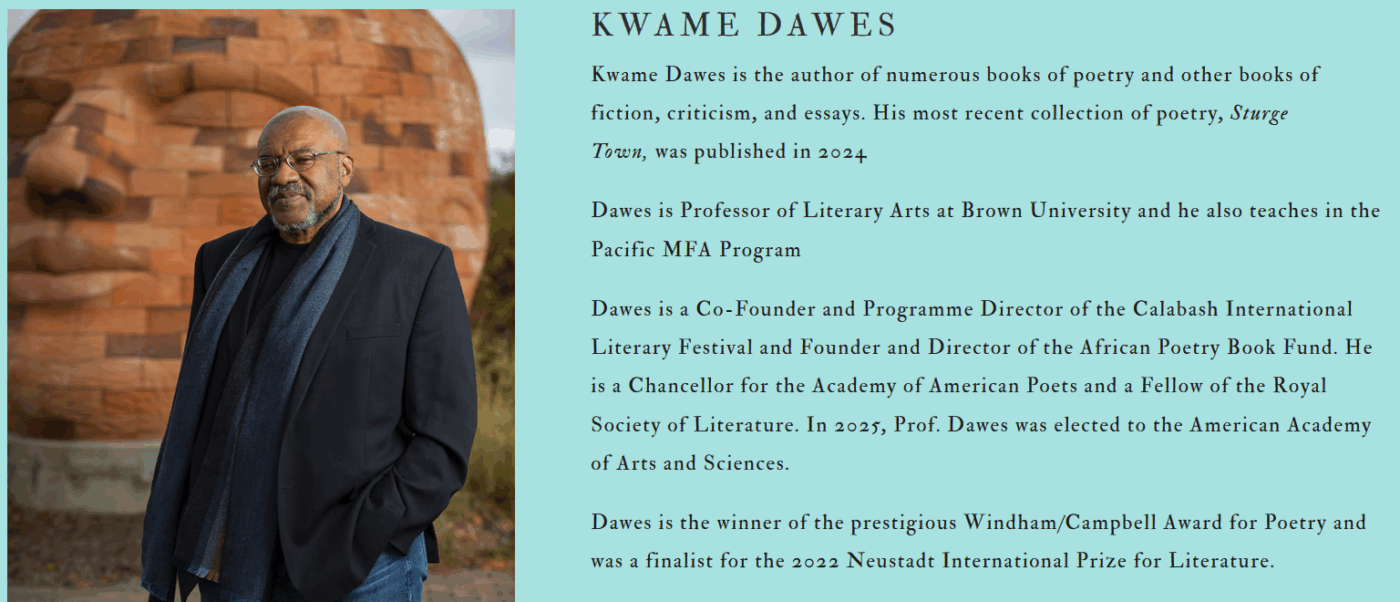

The festival opens on Friday, the 5th of September, with a session with Samson Itodo, who has done incredible work galvanizing the youth voice, vote and democratic participation in Nigeria. He and Omar Freilla, who founded the oldest Black-led worker cooperative development organization in the U.S., will drill into the nuts and bolts of community care, opening into a conversation on reparative justice that looks at successful models in the U.S., Europe and Africa. On Saturday, we have powerhouse roundtables with Sean Henry Jacobs (Africa Is a Country), Bhakti Shringarpure (Warscapes), Ainehi Edoro (Brittle Paper), Angela Wachuka (Nairobi Litfest), Justine Henzell (Calabash International Literary Festival), Selina Brown (Black British Book Festival), and institutional and network builders from Africa, the U.S., the U.K., and the Caribbean, who will be speaking on a range of issues, culminating in a special legacy conversation celebrating the life and work of poet and scholar Kwame Dawes.

We are also excited to be hosting the first New York edition of Inua Ellam’s R.A.P Party, in partnership with The Guggenheim Museum; it’s a live literature event that joins poetry and Hip-Hop, this time against the backdrop of Rashid Johnson’s ongoing exhibition, A Poem for Deep Thinkers. Ellam’s work shows how literature is always in conversation with other forms, music, visual art, and performance, and that building solidarities often happens, not only through analysis, but through joy and celebration as well.

South African icon, Lebo Mashile will join Malika Booker, Mahogany Browne, and Titilope Sonuga for a truly special reflection anchored in the spirit of Ntozake Shange’s poem, “A Daughter’s Geography.”

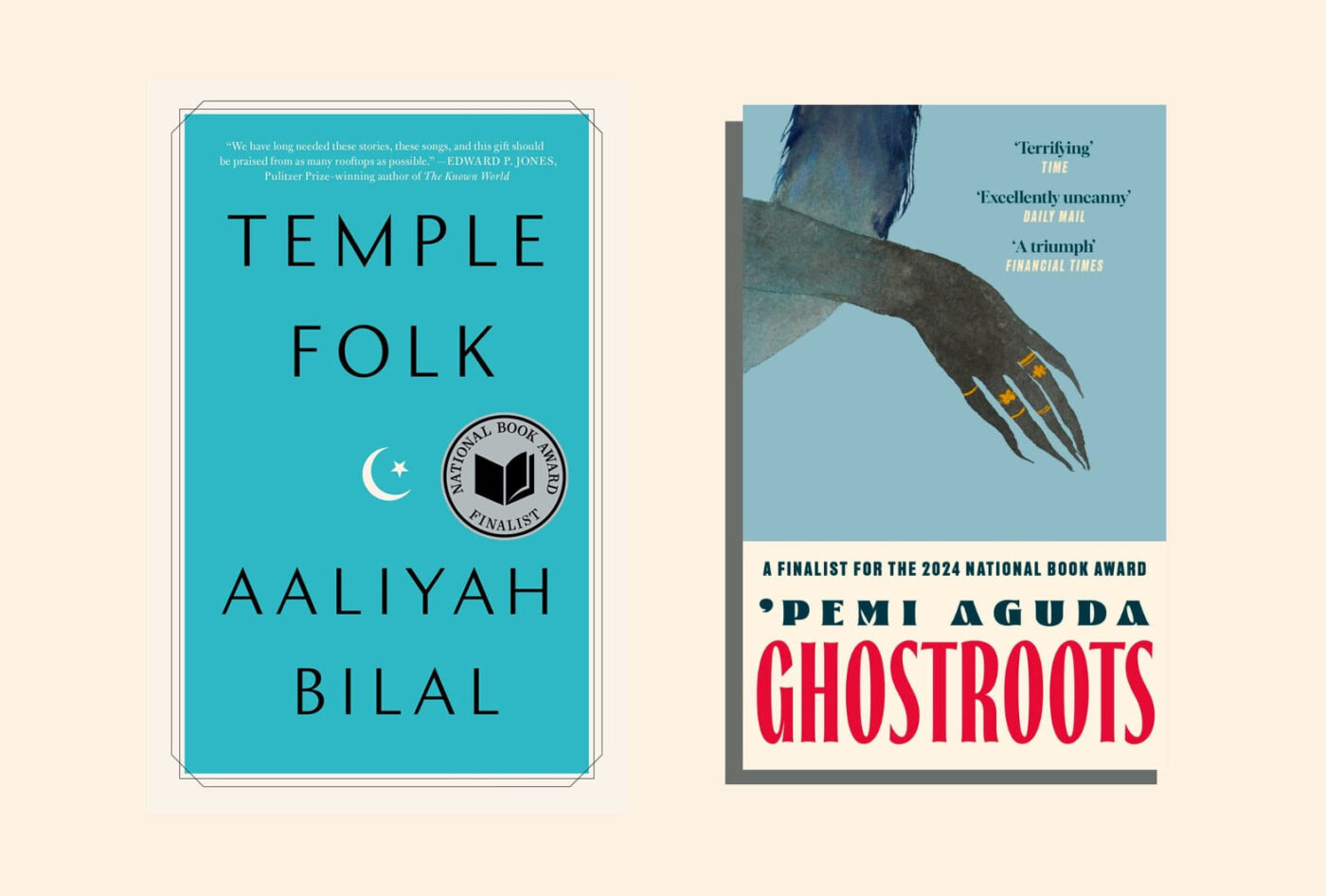

We have a dialogue between two authors with well-received first books: Aaliyah Bilal’s Temple Folk explores the lives of Black Muslims in America with quiet depth, and Ghostroots by Pemi Aguda, a startling new voice in African speculative fiction. This talk is intended to show how the personal and the political, the local and the global, intersect in fresh ways.

Nigerian-American writer and journalist Alexis Okeowo will be speaking from her new memoir, Blessings and Disasters, about making a home in a shifting America, while Howard French will discuss The Second Emancipation, a work that resonates profoundly with the festival’s ethos as it maps Africa’s role in global history and politics and the unfinished struggle for justice.

All together we have over 30 writers, poets, scholars, artists, and organizers joining us over the Festival’s three days

You’re also the founder of the Lagos International Poetry Festival, now in its 10th year. How do the festivals differ?

Lagos International Poetry Festival began with a focus on poetry and spoken word as the entry point to larger conversations about society, identity, and art. It has grown into a space with a strong West African and pan-African footprint. The New York festival inherits that commitment to craft and conversation but widens the frame across literary genres, across the wider African diaspora, and into the cultural and political currents of the city itself. They cohere in their shared ethos: to connect communities, to nurture talent, and to use literature as a tool for building solidarities that can shift cultural narratives.

New York has always been a crossing point of peoples, cultures, and political visions. From the Harlem Renaissance to the Pan-African congresses, the city has served as a crucible where diasporic imaginations encounter the world and reimagine it. Situating the festival here is both a continuation of that lineage and an attempt to renew it for a different moment. The conversations of Achebe’s generation, about independence, language, and identity, echo in today’s debates about migration, belonging, and solidarity. By placing the festival in New York, we’re acknowledging both the weight of that history and the opportunities the city still offers for gathering, cross-pollination, and global visibility.

Sustaining these spaces requires patience, improvisation, and a stubborn belief in the value of the work. They demand an ability to navigate the practical—budgets, visas, venues—while holding onto the poetic—the vision, the urgency, the reason we gather in the first place. The most rewarding part is witnessing the invisible threads that form between people: the collaborations sparked over coffee, the debut readings that launch a career, and the moments when an audience feels seen in a way that is rare in public life.

These events keep me in constant conversation with other imaginations. That can be exhilarating and humbling, forcing me to interrogate my own assumptions, expand my formal choices, and re-engage with the political stakes of the work. They also remind me that writing is a solitary act that lives in an ecosystem of readers, interlocutors, and fellow makers.

What do you hope that this maiden edition of NYBALF contributes to literature and art conversations on the continent and in the U.S.?

I hope it offers a model for how continental and diasporic Black communities can meet in ways that are intellectually rigorous, culturally sustaining, and mutually generative. That it deepens cross-Atlantic literary networks, helps dismantle some of the structural barriers to distribution and visibility, and affirms that our stories, rooted in specific histories, are also part of a global conversation about freedom, justice, and imagination.

The theme for the year is “Radical Solidarities”. What does that mean to you, and how would you like it to be read?

For us, Radical Solidarities is the hard work that asks us to confront power, to be honest about differences, and to commit to relationships of mutual accountability. It insists on structural change and recognizes that no single community, however resilient, can navigate the challenges of our time alone. We want audiences to read it as both an invitation and a provocation: Who are you in solidarity with, and what does that solidarity demand of you?

There was recent news about the U.S. government targeting the Smithsonian for its exhibits on the U.S. history of transatlantic slavery. Amidst other assaults on Black history in America, how do you think writers can and should respond in current times?

Writers have always been custodians of collective memory, especially in times when official histories are being revised or erased. We must document what is happening, the specific policies, the rhetoric, the erasures, but also hold space for the fullness of the lives and experiences that these assaults seek to diminish.

The attack on the Smithsonian is particularly insidious because it targets the infrastructure of memory itself. When the institutions that house our histories are under siege, writers become even more significant as carriers of narrative, and so we must refuse the false choice between art and activism. Our work is to provide the vocabulary for experiences that power seeks to render unspeakable. In this moment, that means writing with precision about what we’re witnessing, but also with imagination about what remains possible.

You’ve invited spoken word artist Titilope Sonuga and myself to join the Board of the Festival. How do you see the Board growing into the future, and what role do you see us playing in steering the Festival in future years?

The Board is central to how we imagine the Festival’s sustainability and integrity, and so it was important to shoulder the vision with a community of cultural workers, writers, and organizers whose perspectives have helped shape both the vision and practice of what we had in mind. Our goal is to expand the Board immediately after the first edition, to reflect the breadth of the communities we serve, people rooted on the continent, across the diaspora, and within New York itself. Its role will be to safeguard the festival’s mission, hold us accountable to our values, and help us imagine new ways of deepening the conversation between Africa and its diasporas.

What is your long-term vision for NYBALF?

I hope the Festival will become a trusted home for Black and African literary and cultural exchange, one that is recognized not just for its annual gathering, but for the year-round networks and collaborations it helps to sustain. I see it as a place where emerging writers find their first audiences, where established voices come to test new ideas, and where cultural workers and organizers can share practice across borders. I hope it becomes part of the city’s cultural fabric, as integral to New York as it is to Lagos or Kingston or Johannesburg. And beyond visibility, I hope it helps shift material realities by opening new pathways for distribution, partnership, and solidarity across the Black world.

______