From the Prism of Black Orpheus: Mapping the Growth and Development of Discourse on African Literature

The Conflict of Cultures in West African Poetry, Ulli Beier’s first essay in the maiden edition of Black Orpheus (September 1957), raises a crucial question that haunted the beginnings of African literature, one that has persisted till date. While the African writer fights against colonial subjectivization, he does so within the ambivalence of using the same language of colonialism to fight the colonizer. This argument would become one of the major issues in our literature, as highlighted in the young Obi Wali’s essay, Towards the Dead End of African Literature, published in Transition Magazine in 1963. In the essay, Wali argues that African writing in English “is merely an appendage in the mainstream of European literature… [and] the consequence of this kind of literature is that it lacks any blood and stamina and has no means of self-enrichment.” However, for Beier—who raised the subject years before, proving that the subject of language has been debated since the emergence of the earliest African novels—Wali’s argument is a wishful ideal and “purist attitude” that is hardly realizable. What Beier achieves in this early essay is lay a foundation for the predominant discourse that would ensue in African literary production long after Black Orpheus had become defunct. The journal did, however, set the tempo for the integration and enhanced growth of African writing through the breaking of barriers between Anglophone and Francophone literature. Beier’s translations of writers like Senghor, Césaire, Leon-Gontran Damas, and Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo, became more readily available to readers as a result. Senghor’s writings, through the translation efforts of Beier, became one of the natural crossovers, language-wise, portraying the struggle of cultural conflicts not only in Anglophone but in Francophone literature as well.

Closely following Beier’s intervention in the inaugural Black Orpheus is Gerald Moore’s essay, Amos Tutuola: A Nigerian Visionary, which brings the author of The Palm-Wine Drinkard into sharp focus against what was then the dismissive critical bent concerning his writing. In Moore’s view, the journey of the eponymous protagonist of Tutuola’s first novel “stands as a clear enough indication that the Drinkard’s adventure is not merely a journey into the eternal African bush, but equally a journey into the racial imagination, into the sub-conscious, into the Spirit World that everywhere co-exists and even overlaps with the world of waking reality.” Moore compares the Drinkard’s journey to that of classical European characters such as Gilgamesh, Orpheus, Heracles, and Aeneas. What makes this appraisal of Tutuola even more insightful is the shift from the subject of literature review to the politics and economics of literary production. This is a feature of the production and consumption of literary materials in Africa till the present time: the vexed subject of the author’s reputation in Africa vis a vis how he or she is perceived in the West.

Moore notes that: “No amount of international acclaim, gratifying though it can be, can count for as much in the development of such a writer as the enthusiasm and support of his own people.” The challenge Tutuola faced then is still the crisis in Nigerian literature today, a subject Egya Sule broached in the 2018 ANA Review, in his essay, Diaspora Positioning, Identity Politics and the Crisis of Contemporary Nigerian Literature. Moore, meanwhile, shows remarkable foresight decades earlier when he avers that:

The imprint of a leading English publisher, though an assistance in the London market, may even be a hindrance in the local one. [Tutuola’s] books are expensive by Nigerian standards; 10/6 or 12/6 are prices that young Nigerians may be accustomed to [paying] for a text-book that will help them directly in examinations but not for “a mere story-book.” Moreover, his publishers are a firm generally associated with the “high-brow” in literature and the dust-jackets of these books, excellent in themselves, reflect this.

This reality, presented in early Black Orpheus, applies today. One can dare say that this has grown worse with the stinging influence of imperialism, which has placed an unfair value on the dollar while African currencies keep dwindling in purchasing power.

One crucial piece in the maiden edition which is also relevant to this exploration is the critical journalism of Janheinz Jahn on the first World Congress of Black Writers, held in 1956 at Sorbonne University, Paris, convened by Alioune Diope, editor of Presence Africaine. Jahn uses his reportage on the conference to also reflect on the importance of the newly launched Black Orpheus. He notes that the conference should ordinarily be of interest to readers of the journal. Nonetheless: “It was painful to remark, however, that the many famous authors who spoke on African culture and its problems, in spite of the reputation they had made for themselves in Western and Central Europe, were almost unknown to their black brothers in Africa and America.” He reiterates that despite Senghor and Césaire’s popularity, their names resonated with the French more than their brothers from other African countries whose experiences are the subject of the two poets. Hence, Jahn asserts that, “This journal was founded in order to break down some of the language barriers, and to make known the black writers who use the French, Spanish, or Portuguese languages in English speaking countries of Africa.”

This journey and focus on the trajectory of African literature continues on its course down to Volume 1 No.2 edition of Black Orpheus. One core editorial focus: writings of the Negritude movement. Issue Two showcases Negritude poets, and this brings Francophone poetry to the heart of literary conversation with other parts of Africa. Jahn introduces us to the poetry of Césaire and notes that “the rebellion of nature is coupled in his work with the rebellion against oppression.” The German scholar goes further to state that the fusion of Césaire’s native sensibility and immersion in Paris informed his identity consciousness. This second issue also has an essay (Mister Johnson Reconsidered) that I would adjudge as crucial to the politics of Black Orpheus and the evolution of ideas catalysed by the change of editorship, first to Wole Soyinka and Ez’kia Mphalele, and later J.P Clark and Abiola Irele.

In Mister Johnson Reconsidered, written by Gerald Moore, we can see the definitional approach to the idea of what a novel is. The scholar notes that Mister Johnson “is the one West African novel that we are tempted to call ‘great’ (if we exclude The Palm-Wine Drinkard, which is a visionary epic rather than a novel)” (emphasis mine). Never mind that Mister Johnson’s author, Joyce Cary, was not African. The kind of position Moore takes in this essay is what Chinua Achebe later defines a “certain specious criticism which flourishes in African literature today and which derives from the same basic attitude and assumption as colonialism itself.” The author of Things Fall Apart argues that the Moore brand of criticism is hosted and upheld when “the latter-day colonialist critic, equally given to a big-bigger arrogance, sees the African writer as a somewhat unfinished European who with patient guidance will grow up one day and write like every other European.”

With more African writers of the first generation gaining ground in not only creative but also critical writings, the politics and reality of Black Orpheus took a different turn. Akin Adésọ̀kàn notes in his essay, Retelling a Forgettable Tale: Black Orpheus and Transition Revisited, that, “Even with changes in its editorial philosophies, as in its handlers, it fulfilled the role its founders designed for it.” Adéṣọ̀kàn observes that Black Orpheusl was so obsessive in “its interest in the literatures of the black world that one of the poets it helped bring to prominence, Christopher Okigbo, in an interview in 1963 criticised the journal for wanting to perpetuate the ‘black mystique’.” Adéṣọ̀kàn goes on to note that the assessment of the literature published in Black Orpheus at that point in time in a way “underscored the journal’s ideology, convincing people like Clark that European literary aesthetics were predominant in African literature and likely for the worse.”

Taking over as editors, Clark and Irele questioned the critical positions taken by earlier Black Orpheus contributors, who were mostly white critics.

Their artistic judgements were called to question in essays like ‘The Legacy of Caliban’ which Clark published in the first edition under his joint editorship with Irele in which they also announced a break with the old regime. Beier’s preference of the Negritudinist sensibility as well as works of art owing their strength to accidental metaphors was criticised not only in this essay but in the general character of the series they edited. However, the Pan-Africanist outlook of the journal was retained in their choice of essays.

This new philosophical path taken by Clark and Irele would influence the outlook of the journal. For one, they changed the series’ subtitle from “A Journal of African and Afro-American Literature” to “A Journal of the Arts from Africa”, and later, “A Journal of the Arts in Africa”. As insignificant as these propositions may be, they reflect core concerns of the editors to change and guide the direction of the journal. This is also reflected in their decision to publish works on traditional African literature, including oral poetry and storytelling. Clark and Irele were clearly deliberate in their choice of what to publish. Hence, taking over the reins, they decided to dedicate an edition to traditional creative productions, and were even more completely radical in later featuring literary-cum-political pieces. In ‘Fresh Vow’, which sets out the new direction of the journal, the editors state that part of the delay in the release date was due to new publishing arrangements they had to put in place. “The other reason for the delay in bringing out this number derives directly from a desire to present the content of this special issue on the traditional oral literature of Africa in a variety of orthographies appropriate to the texts,” they wrote. This deliberate choice to include oral literature with their appropriate orthographies points to the ideological stance of the editors, which foregrounds that for them as Africans, the celebration of oral art form is crucial to the development of the continent’s literature. This fills the void of the absence of indigenous poetic forms in their transliterated orthographic scripts, noticeable under Beier’s editorship.

It is also crucial to note the sparse presence of northern Nigerian writers in the early editions of Black Orpheus, (except for some poems by Ibrahim Tahir, and an excerpt from his future acclaimed novel, The Last Imam). Clark and Irele featured the oral narrative of the Idoma people from Nigeria’s Middle Belt region. This near-absence of northern Nigerian voices in Black Orpheus may also be due to the fact that literary writings in that part of the country were, at that time, mostly in languages other than English, and could therefore not be effectively captured in the journal. Nonetheless, critical observers may note that this dichotomy persists to this day, and informs a kind of boundary that seemingly exists between the popularity of writers from the south and the north of Nigeria.

Black Orpheus and ANA Review: a Comparative Analysis

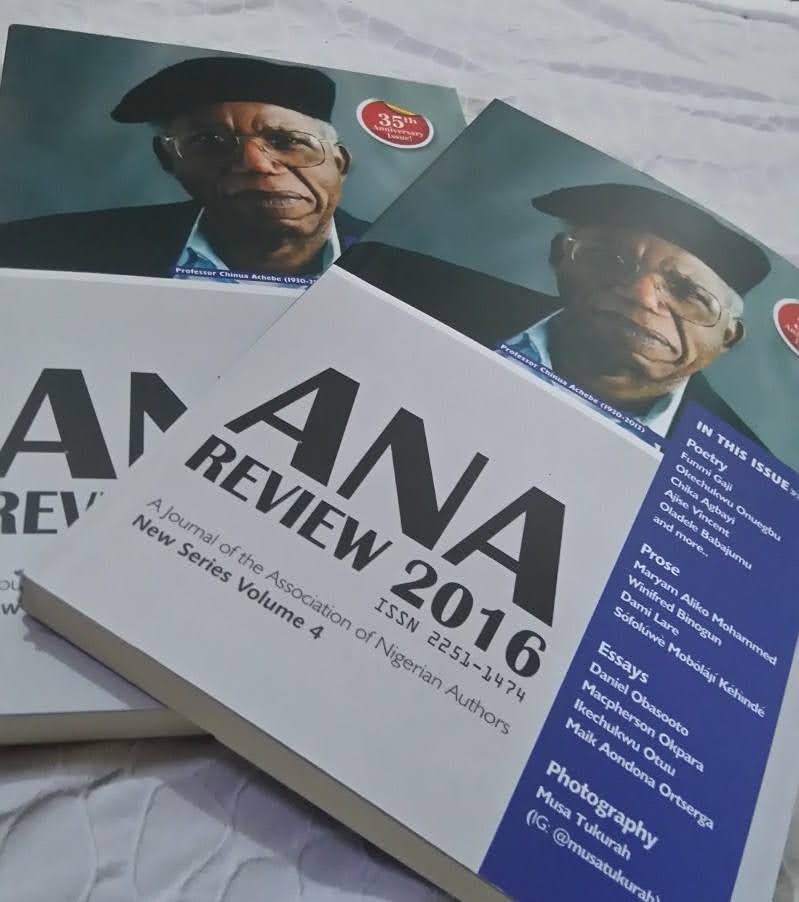

Transitions and shifts in the editorial focus of Black Orpheus over time did not influence the dynamics of the production of the journal as much as political changes in Nigeria. From the Civil War to the economic hopelessness unleashed by successive military regimes that came after the truncation of the Second Republic, the journal ultimately got to a point where it became a bi-annual project during Theo Vincent’s editorship. By this time, Vincent was lecturing at the University of Lagos. Chinua Achebe and several Igbo writers had moved to the East, and the country was starting its destiny of oneness anew. Achebe would eventually found the Association of Nigerian Authors in Enugu in June 1981. The idea was to have an umbrella body that would unify Nigerian writers under one banner to defend its members’ interests and promote literature in the country.

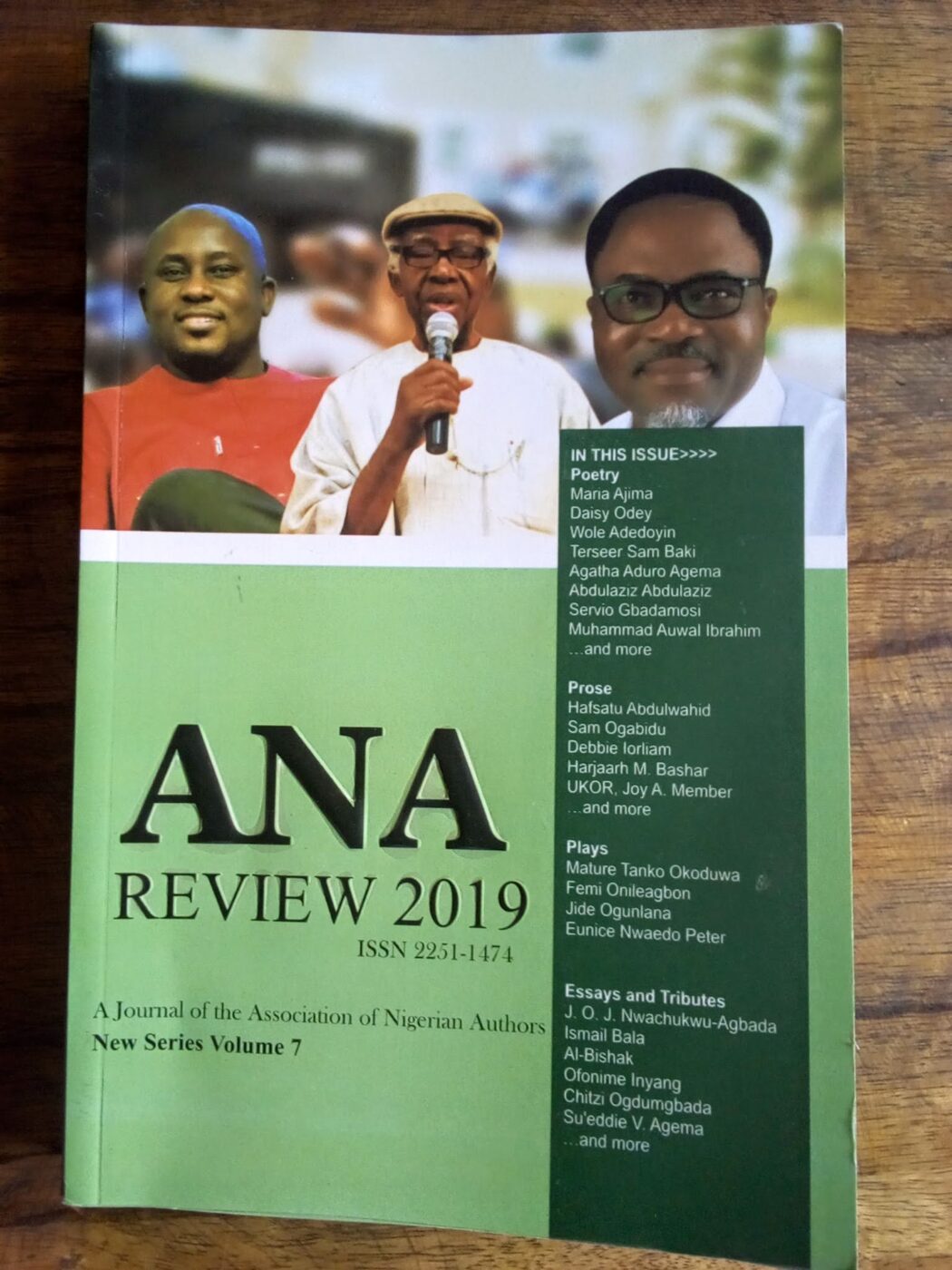

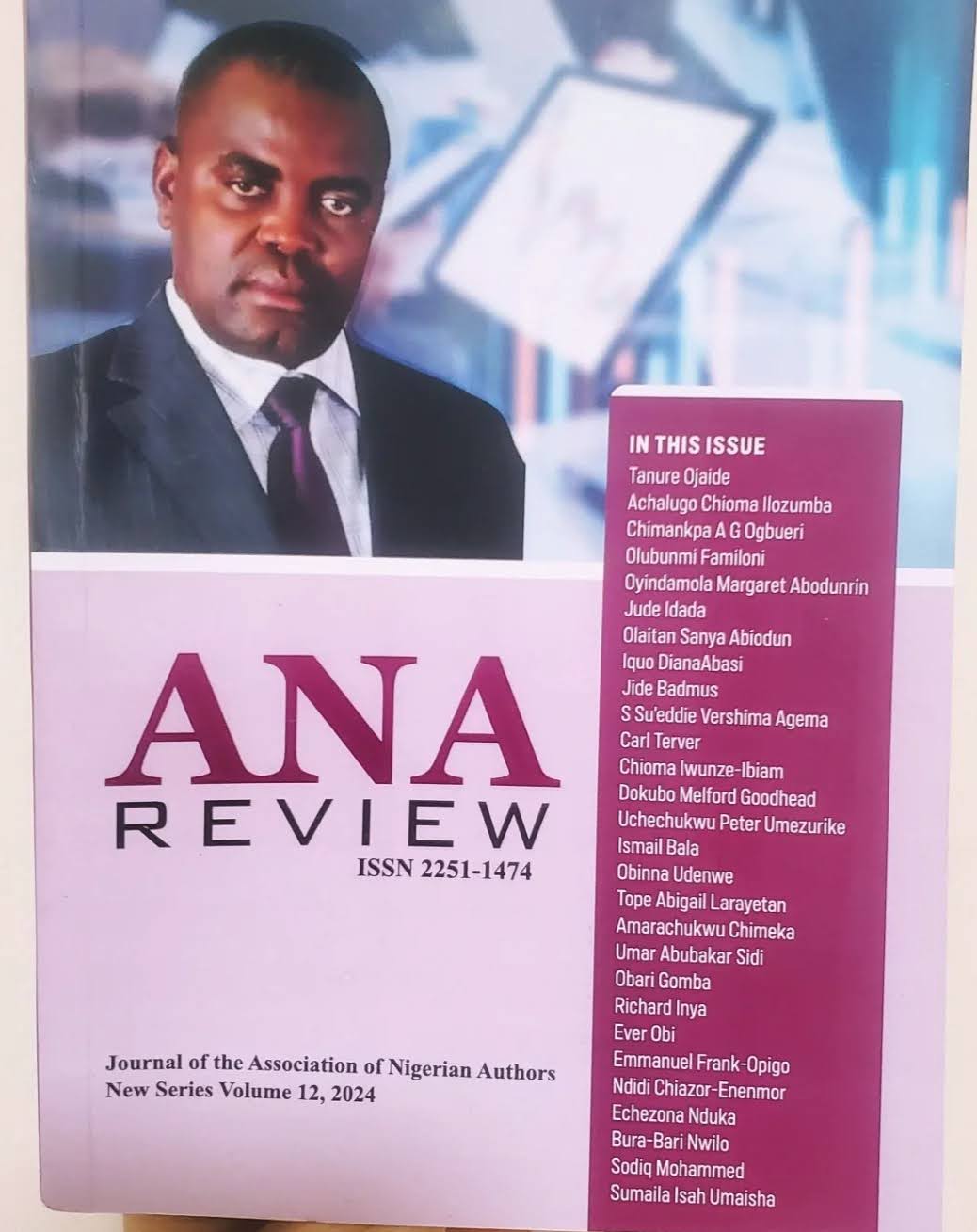

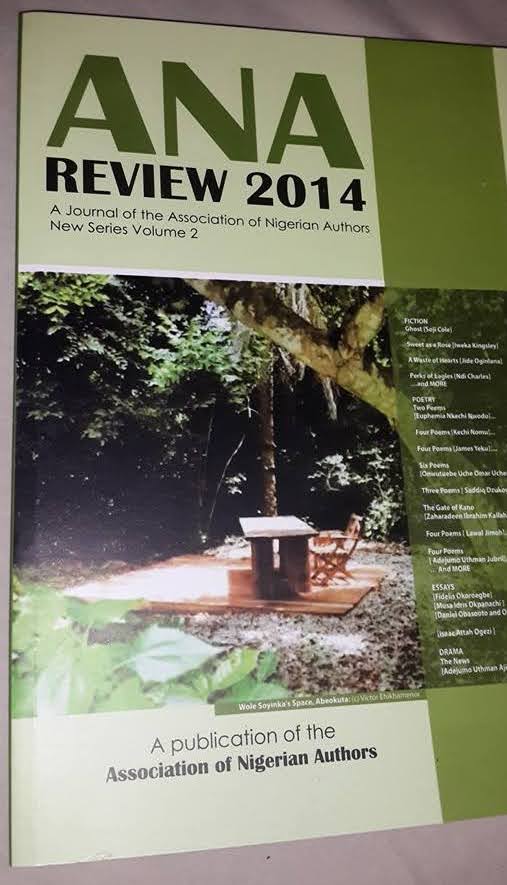

Some years after the Association was registered, it started the ANA Review, which has also gone through its own metamorphosis. Since its emergence, however, it has never ceased to be published annually by the different leaderships of the association. ANA Review started from cyclostyled paper, and then took on a tabloid newspaper format until around 2010 when it assumed its current form – like a proper journal, eventually acquiring its present shape in 2012. Like Black Orpheus, early copies of ANA Review may have been lost to time, as they were not digitized; and a form of retrieval is necessary to properly appraise the literary trends, arguments and themes then—as this current Olongo Africa project on Black Orpheus is activating—in order to preserve the history of what has been produced over the years.

Since the ideological battle of definitional trends and race has been addressed during the period of Black Orpheus, it is safe to say that ANA Review did not go through that journey. What is crucial, however, is that as Black Orpheus raised emerging voices, ANA Review also plays the role of showcasing the talents and tropes of new generations of Nigerian writers. This is most noticeable with Richard Ali’s editorship of the journal, between 2013 and 2016. Most of the poets and short story writers that he included in the Review would go on to become the defining voices of the generation presently labeled as the Fourth Generation of Nigerian Literature. The editorship of ANA Review under Ali was somewhat similar to the conscious move by Clark and Irele to be intentional about the focus of their publications.

Closely following ANA Review, New Series, Vol .3, Ali is more explicit in the fourth volume when he announces that: “It has been a great year for Nigerian literature, with Abubakar Adam Ibrahim and Elnathan John capturing the imagination of the country, the continent and the world, amidst an exciting new crop of writers. The daring and the challenging of limitations, in a bid to pinch deeper into the skin of the times we live… The increase in the number of online magazines like Expound and Praxis has further democratized the publishing spaces. This has largely been a positive influence.”

Perhaps one of the most regarded iterations of ANA Review is the 2018 edition. In this edition is the above-cited essay by Egya Sule, which is crucial to an appraisal of ANA Review and its interconnectedness to the central themes of Black Orpheus, themes that resonate even now. Themes such as the politics of publishing, questions of identity, and the place of the African in the trajectory and destiny of the continent’s literature within the global literary space. “The tendency of African writers to turn particularly to the West not only in the imitation of artistic form, but also to seek to satisfy a Western audience by developing artistic contents, subjecting themselves to editorial sanctions, that exotically market them in the literary capitals of the West” – as Sule notes, is one of the crises of Nigerian literature. That Moore already raised this issue in the time of Tutuola, and Sule still flags up our tie to the West, is concerning, and of course, reflects the continuity of subject from Black Orpheus to ANA Review.

It is also worthy of note that there are similar structures in the handling of Black Orpheus and ANA Review—the editor as the sole individual responsible for what enters the edition. While for ANA, the elected General Secretary of the association automatically becomes the editor of the Review, just like Black Orpheus, he is completely in charge of the decisions as to what is fit to be included. This explains why in the time of Clark and Irele, they changed the scope of materials to be published and even the geography of writers to feature, while Ali tilted his gaze more towards young contemporary writers.

It is safe to say that the convergence of Black Orpheus and ANA Review is that they both strive towards a philosophy of building emerging voices and having a platform where people can comfortably express their own creative will. Though ANA Review is tied to an association, the question of its survival seems more lasting than the timespan of Black Orpheus. This is because ANA does not rely completely on the patronage of donors to keep the Review running. However, this impacts the outreach and distribution of the Review, since copies are mostly for contributors and delegates at ANA Conventions. Also, the logic of ANA making the review an annual project offers a financial relief for continuity. It would serve ANA Review to learn from the example of Black Orpheus and spread its wings to fill the void left by the older publication. Black Orpheus did not only promote the voice of a generation, it built a pathway towards a more robust discourse on modern African literature.

****

Denja Abdullahi is a Nigerian poet, dramatist, playwright, director, arts and culture administrator. He has authored 14 books of poetry, drama, interviews and co-edited critical essays on the writings of Chinua Achebe. He has had a career cutting across teaching, lecturing, journalism and the public service. He was the national president of the Association of Nigerian Authors ( ANA) between 2015-2019 and recently retired as a Director of Performing Arts with the National Council for Arts and Culture, Abuja. He is a UNESCO – certified global facilitator and expert on the intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity and Chairman of Orpheus Literary Foundation, Nigeria. Abdullahi is presently with the Centre for Creative Writing, University of Abuja.