Poetics of the Abject in Adedayo Agarau’s The Years of Blood

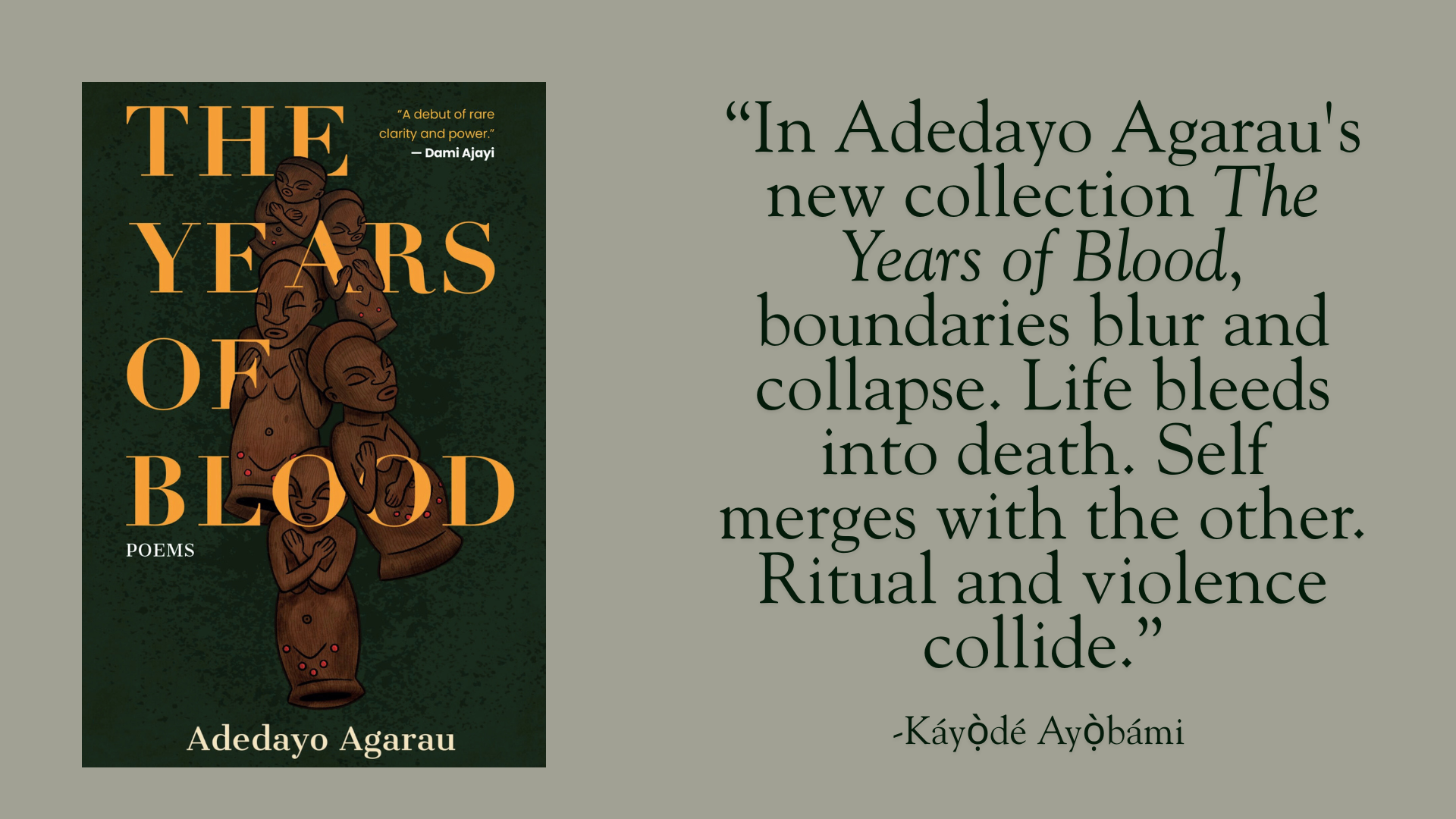

In Adedayo Agarau’s new collection The Years of Blood, boundaries blur and collapse. Life bleeds into death. Self merges with the other. Ritual and violence collide. This collision produces what Julia Kristeva calls the abject, that which exists at the border of our identity, neither fully self nor other, neither clean nor unclean.

Adedayo Agarau belongs to the new-generation of African poets who emerged in the mid-to-late 2010s. His debut chapbook, For Boys Who Went (WRR 2016), established him as a distinctive voice exploring themes of absence and childhood grief. A Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford and MFA graduate from Iowa, he has since published Origin of Names (African Poetry Book Fund, 2020) and The Arrival of Rain (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020).

The Years of Blood (Fordham University Press 2025), his debut full-length collection, marks a shift from personal grief to collective trauma. While his earlier works explored familial loss, this collection examines violence plaguing Ibadan: kidnappings, murders, and political corruption. Agarau centers Yorùbá language and worldview, refusing to dilute his cultural specificity. This collection is both a personal and a national reckoning.

In Powers of Horror, Kristeva describes abjection as “disturbing identity, system, order” and undermining respect for boundaries. Through poems laden with kidnapping, extreme violence, and piercing grief, Agarau exposes trauma’s imprint on both individual and collective consciousness. This collision of boundaries manifests most powerfully in “Ghost of a Dead Boy Writes from Sókà,” where the persona exists between presence and absence. Kristeva argues that the corpse represents the ultimate abjection, that is, what we must thrust aside to continue living. Yet here, the dead child-persona cannot be thrust aside; he remains, writing: “Light seeps out of my body as my blood calls your name.”

The poem forces readers into an uncomfortable propinquity with death itself. When the speaker describes “a child’s skull is a new path” and “a bowl of blood is a festering,” the child’s body becomes an abject matter that repels and fascinates, embodying what should remain buried but refuses to stay hidden.

Moving from individual trauma to collective response, Agarau in “Portent” exposes how communities deploy ritual to contain the threat of disappearance. The priests perform elaborate ceremonies, smearing “a widowed cockerel’s blood,” burying “a goat’s placenta,” in probably in an attempt to curb or prevent further kidnappings through propitiatory action. This response represents a defense mechanism against insufferable anxiety, seeking symbolic control over chaos. Yet the poem’s final image confounds this hope: “gunshots spoiled the night with fear. Birds the next morning cried like wolves, like the woman whose children were shot in their sleep.”

The ritual fails, exposing how symbolic systems collapse against real violence. In the face of such collapse, the poems give voice to pervasive dread. In “Wind,” this manifests as anxious repetition: “It could be me whose blood is crying… It could be my father… Or sister… It could be my mother’s headless body.” The repeated “It could be” becomes an incantation of possibility, in a landscape of constant violence, anyone could be the next victim. The ghost-child whispers “I am here” while the mother cannot hear, illustrating grief’s isolation in its heightened intensity.

The poem “Ibadan” channels grief into a raw, unfiltered rage. Here, the world is a predatory landscape: a husband sacrifices his wife for wealth, and “everywhere a weed grows there is a wild mouth eating children.” Agarau uses fragmented syntax and removes traditional punctuation to mirror the psyche under duress. Without commas or periods to provide boundaries, the trauma bleeds across the page. This reflects the kidnapping itself, which dissolves into a blur of atmospheric confusion:”the morning I was kidnapped / when they found me I was standing by a pole insensible.”

The use of the word “insensible” and the passive construction of the sentence suggest dissociation. This is psychological splitting, a survival tactic in which the self detaches from an experience too overwhelming to process. By stripping the poem of its structural “borders,” Agarau forces the reader to experience the same spatial disorientation the victim feels. However, the most serious threat to selfhood is not external, but domestic. Abjection occurs when violence emanates from the very people meant to provide protection.

In “Arrival,” the betrayal is harrowing and somatic: a great aunt stirs “rat poison in amala.” In “Ibadan,” a mother “pounds the head of her newborn” until life fades into the “silence of crickets.” These acts do more than kill; they collapse the social order that should protect children. When nurturing is transformed into a death threat, the “inside” becomes toxic. The ultimate breakdown of this order is captured in a single, terrifying image: the persona’s mother screaming not for the child, but at the “blood in my mouth.”

This breakdown is evident in the collection’s treatment of ritual. While “Portent” shows ritual’s failure to prevent violence, “Arrival” goes further, exposing how ritual itself becomes violence. In the Yorùbá belief system, witches are sometimes considered as “abiyamọ abọ̀já gbọ̀rọ̀gbọrọ,” which roughly translates as “caring mothers whose scarf is long and broad enough to back a child.” They represent the ultimate cultural safety net. Agarau subverts this image entirely. He presents a “company of witches” gathered around a baby cot, not to protect, but to “pick the body out with a needle.” In psychoanalytic terms, ritual is meant to be a “container” for the psyche’s fears. Here, the container is shattered. The ceremony of care is transformed into a calculated assault, leaving the persona, and the reader, with no sacred space left to retreat to.

The Years of Blood displays resistance through compulsive repetition. In “Entrance” the persona is in recursive nightmare: “my brother calls my name… he calls my name, and I answer… he calls again” enacts this repetition. The poem’s semicolons function like stitches attempting to suture experiences that refuse cohesion, while the persona admits, “I know the graves I have made myself are why my body is never at rest”. Acceptance never arrives. What remains is melancholia—mourning that cannot be completed when the dead keep speaking, when bodies cannot be properly buried. Throughout these poems, grief emerges not as a process with clear stages but as what Dominick LaCapra terms “empathic unsettlement” in his book Writing History, Writing Trauma, in which a state resists resolution. The reader cannot achieve a comfortable distance from trauma. When the persona in “Ghost of a Dead Boy Writes from Sókà” asks “How are you? We arrive numb, forgetful of home,” the question implicates readers in the ongoing catastrophe. Kidnapping, violence, and other atrocities remain rife in Nigeria.

The poems in The Years of Blood largely circle through unresolved grief. Works like “Prelude,” “Christmas,” “Ileya,” “Litany in Which My Father Returns Home Safely at Night,” offer moments of tenderness, yet the collection nearly refuses the consolations of narrative resolution or therapeutic closure. The abject seems impossible to expel because of how it constitutes the traumatized community’s fundamental condition. Children disappear, corpses multiply, rituals fail, and the dead speak from graves that cannot contain them. The collection’s accomplishment lies in its unflinching account of how violence overwhelms the symbolic systems meant to manage it, leaving subjects suspended between worlds, between life and death, in the terrible space of abjection where grief becomes not a process to complete but a durable state of being.

Káyọ̀dé Ayọ̀bámi is a Nigerian poet and an African literature enthusiast, interested in Academics and Yorùbá translation. His works have been published or forthcoming in Echelon, icefloepress, Olongo, Àtẹ́lẹwọ́, PoetrySangoỌta, Isẹle, Ake Review, South Florida, and elsewhere. He was shortlisted for the Ake Climate Change Poetry Prize (2022). He can be found tweeting on X about literature @kayodeAyobamii