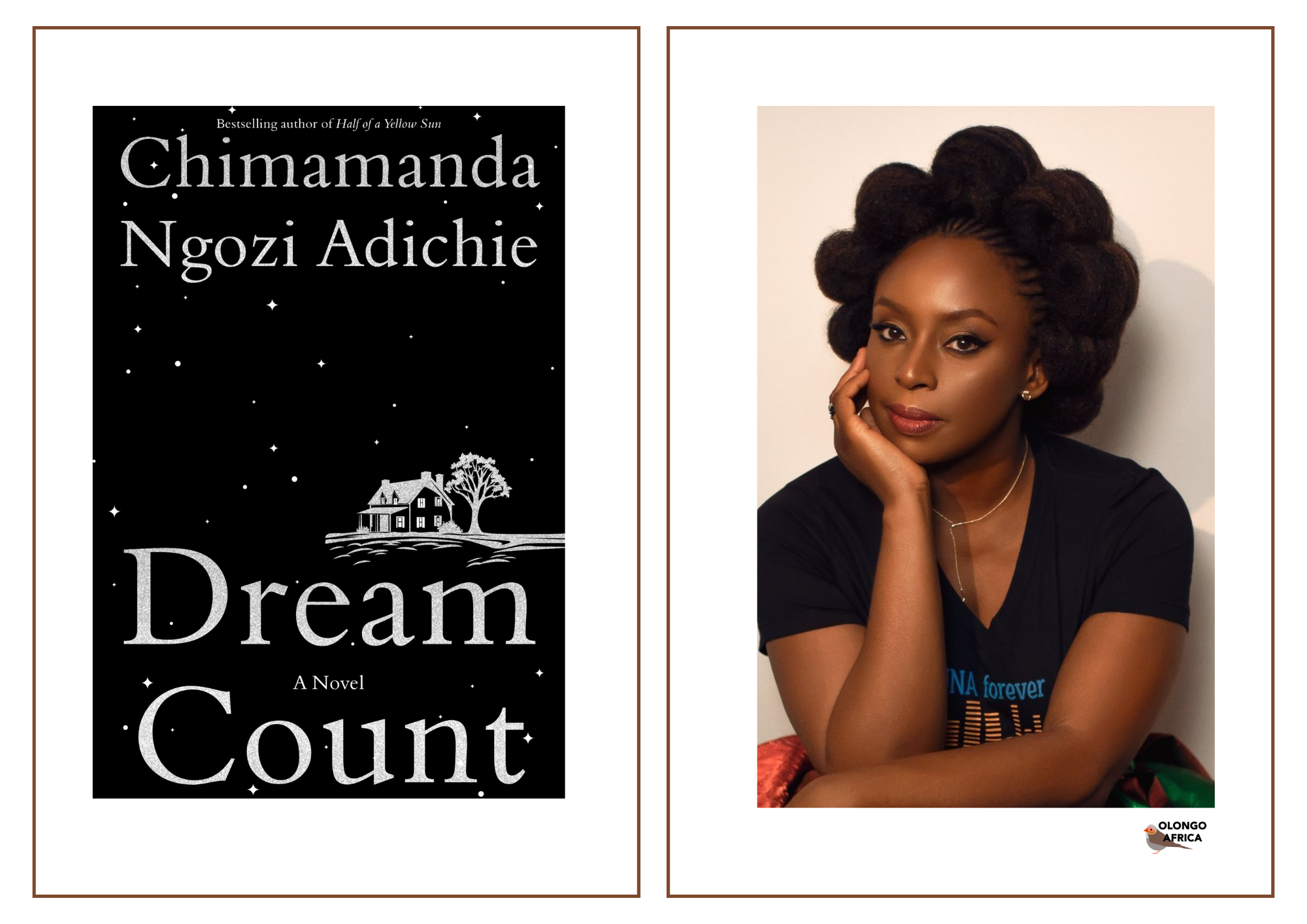

In Dream Count, Adichie Denies Us Catharsis

Novels often build toward closure, offering readers a resolution or tying loose ends, but in Dream Count, Adichie resists this expectation. She leaves you with crescendoed emotions, emphasising her central concern: the elusive nature of dreams as mediated through memory. This, alongside the novel’s interrogation of how privilege grants and strips women of agency, forms one of the two dominant threads that run through her latest contribution to literature.

Dream Count is a tapestry of a four-part story narrated by four women, each woman’s story serving as an anchor in the braid. Adichie’s mode is primarily through recollections of the women: Chiamaka, Zikora, Omelogor, and Kadiatou. During the COVID-19 lockdown, Chiamaka recalls her search ‘to be truly known’ by past lovers. Zikora, five years before lockdown, muses on how life denies us that which we grapple for. Omelogor recounts all she has with pride, until a nosy aunt reminds her that she is childless and in her forties. Kadiatou, the Guinean immigrant and Chiamaka’s housemaid, accepts her lot in America and is on her way to securing the American dream for her daughter when tragedy strikes, upending her life, leaving her bare to America’s bile. Their handling of this, the other women’s indignation at Kadiatou’s persecution, and disbelief that her credibility is questioned, expose how a lack of privilege influences how survivors of sexual abuse are publicly perceived and believed. Thus, disadvantaged women are expected to compensate by being Mary-like victims, spotless and near-saints.

More often than not, fiction avoids featuring women experiencing reproductive processes or challenges, except for when they are utilised as a plot accelerant. Dream Count veers away from this, peppering each woman with periods, fibroids, and PMS. It exposes the casualness or disdain with which these conditions are regarded. Chiamaka says this of menstruation: “My mother had raised me to hide all incarnations of my female body, burn used pads in the evening at the back of the house with nobody else around, wash any bloodstains furtively, so nobody noticed”. In the next scene, it is established that Kadiatou’s knowledge of Chiamaka’s fibroids ties her to Chiamaka, as she recalls that her sister, Binta, suffered the same.

Binta and Chiamaka’s experiences are dissimilar and similar. Their conditions are treated with levity and secrecy, with disastrous consequences for the former. Bappa Moussa, Binta’s uncle, refuses to let her undergo surgery to have her uterine fibroids removed until he is told that it could stop her from having children. This mirrors the reality in patriarchal societies that, outside of being and performing the role of “bearer and haver of wombs”, women are treated like afterthoughts, means to an end.

Also, the emotional turmoil surrounding Zikora’s abortion isn’t glossed over. Adichie doubles down on the hesitance and Catholic guilt Zikora feels while making the practical choice for herself at that point in life. In the end, her choosing to keep her next pregnancy decades later as a successful lawyer underscores how reproductive rights give women agency. For the teenage Zikora, pregnancy was a curse she did not wish to be afflicted with. As an adult, it is a welcome development, despite the uncomfortable context in which she has to have the baby—by a boyfriend who bolts after she shares the news with him.

Dream Count’s women repudiate or propagate harmful cultural norms. Chiamaka and Zikora long for a husband and wedding– two things they have been taught make women whole. Omelogor, from a less privileged home, cares little for marriage and immerses herself in achieving affluence through unethical means. Kadiatou longs to be loved, but knows to up and leave when Amadou, her childhood love, betrays her trust. Their mothers appear as voices of cultural conditioning. For Zikora, the mother nitpicks; for Chiamaka, she questions her hesitation; for Omelogor and Kadiatou, they passively accept their daughter’s choices. Through these intergenerational dynamics, Adichie interrogates the intangibility of dreams, especially those that society dreams for women. Zikora and Chiamaka desperately chase romantic relationships until life lulls them into counting their dreams for Chiamaka or acknowledging its futility for Zikora. Omelogor interrogates her reasons for being unpaired despite several dalliances, before considering adopting a child. Kadiatou and Omelogor, though worlds apart in class, both reject the notion that love must come with self-erasure, a quiet defiance that sets them apart from the two above.

In a world where women’s autonomy—both bodily and legal—is constantly under threat, Dream Count does not shout its resistance. Instead, it whispers. Adichie offers no slogans, no neatly packaged empowerment arcs. What she presents, instead, is quieter and more radical: a story that treats women’s indecision, memory, and aging not as narrative detours, but as central concerns. This, too, is a kind of protest that doesn’t seek to resolve but to reckon.

As in Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun, Adichie relies heavily on interiority for character development. In these earlier novels, readers encounter others through Kambili’s perceptions or the intertwined accounts of Olanna, Richard, and Ugwu. In Dream Count, characters are not always given the space to define themselves independently. Instead, they emerge faintly, refracted through memory and filtered interior monologue. Chiamaka’s lovers are recalled in brief snapshots from lockdown; Kadiatou, Omelogor, and Zikora’s arcs are deeply rooted in backstory. This strategy has served Adichie well in the past. In Purple Hibiscus, for instance, characters like the exuberant Father Amadi and the reticent Beatrice are fully realised through Kambili’s observations. Similarly, in Half of a Yellow Sun, the alternating perspectives of Olanna, Richard, and Ugwu fill narrative gaps and advance the plot. In Dream Count, however, this method feels stalled, more concerned with what was than what is. The result is prolonged character exploration without narrative movement. Through Zikora’s perspective, we learn of her tense relationship with Omelogor: “Omelogor was always so singularly sure, so confident, her certainties thick with judgment, as if she was saying that everyone else was inadequate”. Later, Zikora reflects: “Nigerian bankers were cesspits; if you scraped the hands of all the successful bankers, you would get fetid manure. Omelogor had no doubt soiled hers. Maybe she was about to be caught, and graduate school in America was her planned escape”. These contribute to Omelogor’s characterisation.

While Dream Count’s strength is its deft interiority, it leaves craters in how plausible its progression is. Sections of the novel lapse into long, sanctimonious observations that diminish its relevance to character traits. For a sarcastic character like Omelogor, this could be overlooked as her propensity for having an opinion on everything, even when not asked. Chiamaka’s sections, in contrast, especially when Adichie veers into a critique of American academia, feel forced for a character previously established as dreamy and whimsical. The first-person narration in this part heightens the dissonance, making the critique feel out of character and prompting questions about whether these reflections align with Chiamaka’s established voice, or is Adichie overreaching.

As always, Adichie’s language stuns without effort. Several passages from the book show that her tinkering with language yields new meanings and sleekness. While Kadiatou grapples with terror after being assaulted, her thoughts are laid so “This image of the court bulked forbiddingly in her mind. They would hack at her with a machete and invite vultures while she lay, still alive, her open wounds exposed”. Chiamaka’s realisation of her complacency with Darnell is almost poetic: “He squashed my smallest pleasure, and I helped him flatten them, sinking myself into the mean crevices of his will. I look back now and see my weakness in such sharp relief, being pliant and docile in exchange for nothing; the clarity of hindsight is bewildering. If only we could see our failings while we are still failing”. With Kadiatou’s thoughts, she thickens the emotional undercurrents of her crucifixion by the American media. With Chiamaka’s looking back, Adichie exposes the insidiousness of self-erasure in romantic relationships.

Readers of Adichie may find Dream Count jarring in its refusal to realise what is expected to be its vision–these women becoming more decisive than they were when readers met them. She opts for something else, showing that as life winds down, as humans achieve agency, one begins to take stock. As in Americanah, Adichie discards convention for her message. Instead of being spectators of action, Adichie makes readers watch interiority. Dream Count intends to stir one to ask questions and sit with them. It lets you ponder without foraging for answers. As a novel, it may feel weighty, in a heavy-on-the-tongue way perhaps, because it addresses subjects previously glossed over. Still, it realises its vision–an unsettling unearthing.

Chideraa Ike-Akaenyi is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in Ubwali, Communa, Agbowo, and elsewhere. Her writing explores adult enuresis, grief as a catalyst for self-ideation, and revenge as a channel for healing. She won the 2024 Communa Prize for Fiction and was twice shortlisted for the Awele Creative Trust Award (2021, 2023). She also mentors young writers through the SprinNG Writing Fellowship and is an alum of the 2023 E.I. Okonkwo and 2024 Ubwali workshops.