The power of our Muse lies in her meaninglessness – Gueorgui Pinkhassov

I am on Instagram fiddling through images. I am looking at pictures by Fati Abubakar. The account @bitsofborno is titled Yerwa. Maiduguri, also called Yerwa by the locals, is the capital and largest city of Borno State in North-Eastern Nigeria. These images are grids of boxes in a digital gallery documenting quotidian details of Borno State.

There is an image titled Fashionable Sisters, Maryam and Fatima: it is a deliciousness of colours. The visual field has two girls, one maybe about two years older and taller than the other, with their backs resting on a brick-red wall, their head covered in pink veils dressed to impress. They both spot cheap dark lensed rubber eyeglasses. The older one has a bright yellow frame, while the younger girl blends with a pink frame. The girls are not looking at the camera, they stare forward, ahead. The photographer is in a conversation with them only through the sides of their faces. Their flow of thoughts is far, at a distance. The thoughts of the photographer converge with theirs at this angle that produces the photograph. It is the Eid Festival in Borno, their fashion is bold and bright. The previous day might have begun with a bomb blast and a curfew imposed. Today everyone dresses to celebrate. There is a flow between elation and conflict.

“I insist when I photograph people, I photograph them in a way I want to be photographed.”

Fati Abubakar was born and grew up in Maiduguri, Borno State. With her camera, she braved the odds of bomb blasts and a terrorist group that termed education as forbidden as well as a patriarchal society, where the ideal visual of a young woman is not that of her walking around town chasing pictures. Chronicling everyday life in Borno, in the heat of an insurgency, Fati sets out with her camera as a canvas and her eyes as brushstrokes, to create an alternative ‘real’ image of Borno not just as a war zone of a theatre of trauma but a place of humanity and hope in a time of crisis.

Her ‘Bits Of Borno’ project began as a modest campaign promoted on social media platforms, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram through which these pictorial bits in story form will gradually sprinkle from Borno to the whole of Nigeria and capture the attention of a global audience.

In most of her photographs, we find a ceaseless documentary of happiness, with the camera lens gravitating towards children. Fati’s photographs are not the ambitious spur of the moment, once in a lifetime captured warzone images. They are deliberate arrangements of thoughts and a conscious effort to depict humanity in its real form.

The photographer asks her subject to pose for a picture. This girl in a hijab finds a wall in the middle of a narrow alleyway littered with plastic rubbers and water sachets to lean for support. She directs her vulnerability, shattered dreams, fear, and a tinge of hope at the camera. A boy running towards this path comes to a halt like a pedestrian at a red sign of a traffic light, determined not to interrupt this flow of consciousness. Behind him is another boy pushing forward a bicycle, gawking or appreciating the effort put into a photograph. The photographer pushes her body backwards, leans her head forward and aims the camera at the photographed who is ready for the click sound or a flashlight of the camera.

In another image there are two toddlers, each holding a pink balloon. The older one is in hijab while the younger one has her oversized Ankara blouse falling down her left shoulder. The photographer captures this image with both children looking away from the camera. There seems to have been a premeditated pose that was altered just before this image was taken. The children are delighted with the balloons. The older one looks towards the girl on her right, but not at her, her gaze is further forward, her right hand holding the balloon filled with her air in elation, maybe passing a message to someone somewhere using facial expressions only. The younger one is looking directly at the obliviousness of the older girl, and has her eyes full of questions. Her balloon is not as filled as her partner’s, and her mouth is captured blowing air to refill it.

There is victory in this photograph. The unawareness of these children to the conflict serves as a perfect template of what Bits of Borno aspires to. The comfortable innocence of children in the midst of the crisis of humanity, of how even trauma cannot overshadow excitement. The photographs are a collage of mirths in a field of agony.

“Years from now, generations will want to know what happened.”

For over a decade, Maiduguri has been devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency leaving the region in a state of infrastructural turmoil and communal disarray. Slowly, the insurgency extinguished life out of the once vibrant and economic town. In April of 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped more than 276 girls in a secondary school in Chibok, Borno State. The incident drew international attention to the students’ plight and the extremist terrorist group that claimed responsibility for the kidnappings. The world’s eyes from then on became focused on Borno State.

Boko Haram, which literally means ‘Western Education is Forbidden’, however had been attacking schools right from the beginning of the insurgency. In a culmination of the crisis, the Borno State Government had to close down all schools in May, 2014. For two years, public schools remained closed. Education became forbidden.

But as the world’s attention, especially the Western media was focused on Chibok and the ruins and devastation in Maiduguri, Fati’s images covered the blind spot. Her work while acknowledging the destruction did not explicitly focus on the angle of trauma. She dismantled the Western view by confronting the violence as an artist curating humanity. In her posts she matches the photographs with visual storytelling that come as a form of documentation of the impact of the insurgency and the resilience of the people, while exploring cultures and traditions as a means of archiving the present.

“How would you like your photograph to be taken?”

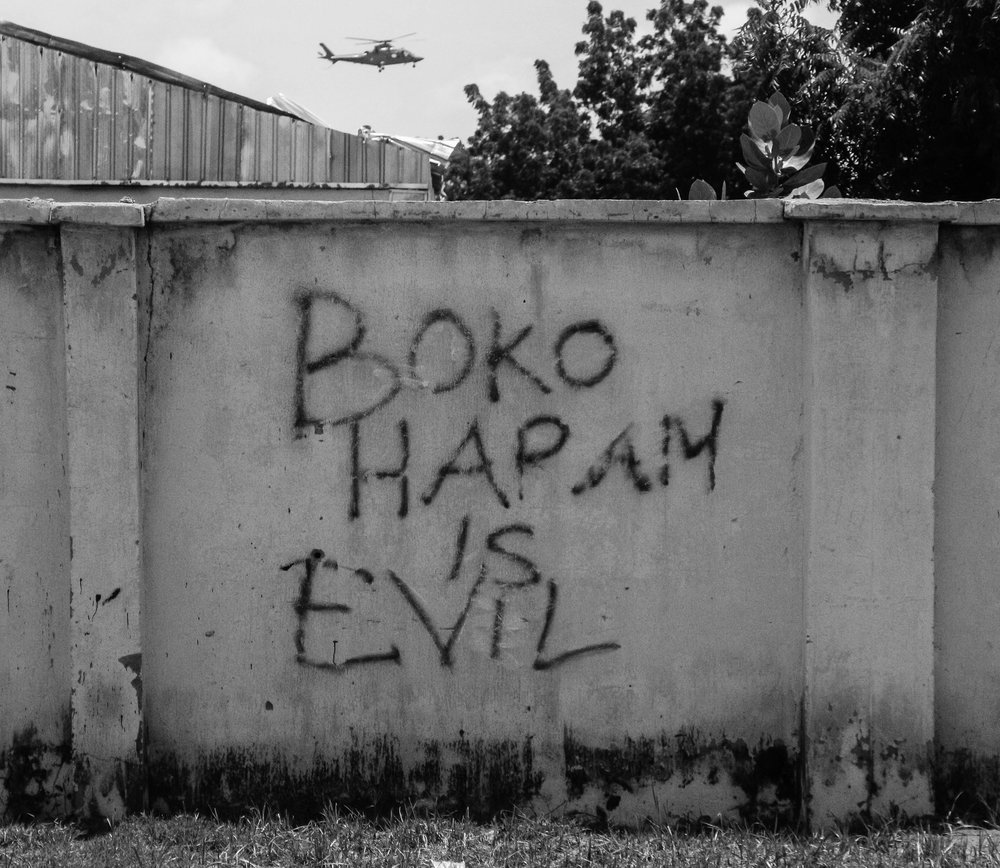

The images in Bits of Borno progress like a voyage. Here is a child hugging a teddy bear in an internally displaced camp, so tights her veins show. There is a world of conflict in her eyes, in her childhood; here is an old woman pulling and dropping rosary beads with one hand, her face is a design of wrinkles and frailty that rests on the palms of her other hand, eyes closed, there is a crisis of conflict and old age; here is a ghost town, with graffiti on a burnt wall: Boko Haram is Evil; here is a widow struggling with grief; here is a widow posing with a portrait of her dead husband, healing; here is an image of tension, other times a colourful Christmas; here is a new gallery: photographed by flashlights from phone cameras, an intense dim dreamy image bringing to life a night party, bringing to life a buoyant student life amidst bomb blasts.

As you scroll the here and here of Bits of Borno, occupying the flow of the photographer’s conscious decisions, you feel your breath becoming calmer and the consciousness of conflict hushed.

Fati understands that her job is compassion. She takes time to engage with the photographed, makes sure children are clothed and offers them an image of dignity. “How would you like your photograph to be taken?” she would ask. The photograph she produces is a gift of hope in a field of violence. She says, “when they say there’s an insurgency here, people assume it’s nothing but death and despair, I want to change the image. You can see, everyday life continues.”

Searching for Happiness?

Fati Abubakar roams the streets to find the happy ones. “I always ask them, how would you like a picture?” she says.

Her works are fixated with understanding and empathy between the photographer and the photographed. “I want the person to be happy with his image,” she adds.

However, not all stories in a field of catastrophe can be laced with happiness, no matter the obsession. In her series, The Other Abducted Girls you find photographs as silhouettes and shadows. It is estimated that at least 40 women and young girls have been abducted in each village of Borno State from 2009 by the terrorists and used as sex slaves, maids, and suicide bombers. With the recent superiority of the Nigerian military and the support of youth vigilante groups, more women and girls have been rescued. After a couple of weeks of therapy and deradicalisation, they are reunited with their families. These series of photographs recount the horrors of brutal times. The photographed girls are shadows of trauma, their faces hiding behind veils, away from the camera or in shadows surrounded by filters of sweat, colours and penetrating light. There is a search for happiness, but these encounters are somber.

The insurgency in Borno affected the predominantly young population both physically and mentally and they began a reawakening to say enough is enough to the violence and fish out the enemy, as such the Civilian Joint Task Force was born. They support the military, go on searches for Boko Haram terrorists and set up guard in every area in the city. In her series Vigilante, young men search for happiness by wearing their crisp green uniforms and bowler hats, posing for the photographer with their local Dane guns and assortment of bullets wrapped around their shoulders. These are men of valour; they are survivors of the terrorist scourge. Thousands of other men have died in the fight against Boko Haram. They leave behind wives and children. Widowed, in a series of photographs captured by Fati, these women are trying to heal by searching for happiness. Here, the photographed encounters the photographer by holding the picture of a dead husband. The face of the widow is out of the frame of the picture, the focus is on her hands holding delicately another image, a portrait of a young man full of life. I imagine the process of taking this picture, of a widow rummaging through piles of memories to find pictures of grief, to raise that grief and hold it to a stranger using the minimal amount of fingers, and minimal amount of effort, not holding on too much, but just enough to produce another photograph of grief of healing. Images are the closest we find ourselves to the dead, as reservoirs for grieving. Do the widows during the encounters of this process burst into sudden tears, how can we reconcile politics of witnessing in this conundrum?

Simple and everyday strength

Since getting critical acclaim from her works shared on social media, Fati Abubakar has gotten numerous requests for interviews and had gathered her thoughts over and over in various platforms across various countries discussing what she learned about the power of resilience, love and hope through photography:

I felt our stories had to be told. Everyone was focused on the issue of internally displaced people, and I wanted to do something different. I was tired of the trauma narrative, so I diverted from it.

The insurgency has been portrayed from mostly one angle, which is devastation and death, and for the rest of your life, you will be labelled as something that came out of there, something that is depressed.

I felt our stories had to be told. Everyone was focused on the issue of internally displaced people, and I wanted to do something different. I was tired of the trauma narrative, so I diverted from it.

People fail to understand how truly strong we are as a people. How we have loved through this tragedy and continue to have the ability to wake up and try to have a simple life.

Stories of bravery, courage, sheer strength and beauty are what I find when I see my community through the lens of resilience. The conflict is ongoing, the humanitarian crisis is daunting, our problems still exist. Yet, every day I marvel at how the human spirit is able to endure all this pain and find strength to wake up, get dressed and go to find a way to fight this insurgency or simply to just teach or to go school or to see a counsellor or to eat or to play for the local team.

Yes, I’m chronicling every bit and piece of Borno state as I can at the moment. Fifty years from now, people will wonder what happened during Boko Haram. I think it’s imperative that we have those images to show those generations that this is what happened to your grandparents.

What I love about being a photographer is the ability to capture and freeze a moment in time and eternalise it. Photography makes you delve into history, and it creates conversations around a specific topic that makes people think extensively about life and how to improve it.

You can see some good coming from this.

I am currently struggling with the trauma of documenting trauma. I hope to find ways to deal with it.

“A photograph is also constituted by what’s outside the frame, maybe particularly so.” – Emmanuel Iduma

The photographer is in a conversation with the photographed. The resulting image is the result of an encounter. A sum total of a negotiation and an agreement, back and forth, on poses, lights and angles. The photograph contains hope to a distant viewer, registering in your subconscious the still view of a process, of a conversation of an encounter.

Despite the insurgency, life goes on in Maiduguri. Just like in any zone of conflict, despite the destruction, life actually never stops. The cycle continues.

There is devastation and there is trauma. There are strangers and there are familiar faces. There are friendships, and there are childhoods. There is loss, but there is resilience. A lot will change, but not an image, not an encounter captured in a photograph, not the stream of flow of consciousness etched into a still image thinking in bits and pieces of Borno.

Sada Malumfashi is a writer living in Kaduna, Nigeria. His fictions have appeared in Lolwe, Bakwa, Transition and New Orleans Review. His essays and creative nonfiction have appeared or are forthcoming in The Africa Report, Saraba Magazine, This Is Africa, Bakwa Magazine and Music in Africa, among other venues. He is a fellow of the Goethe Institut-Sylt Foundation Writing Residency and Reporters Without Borders Germany Scholarship Program.