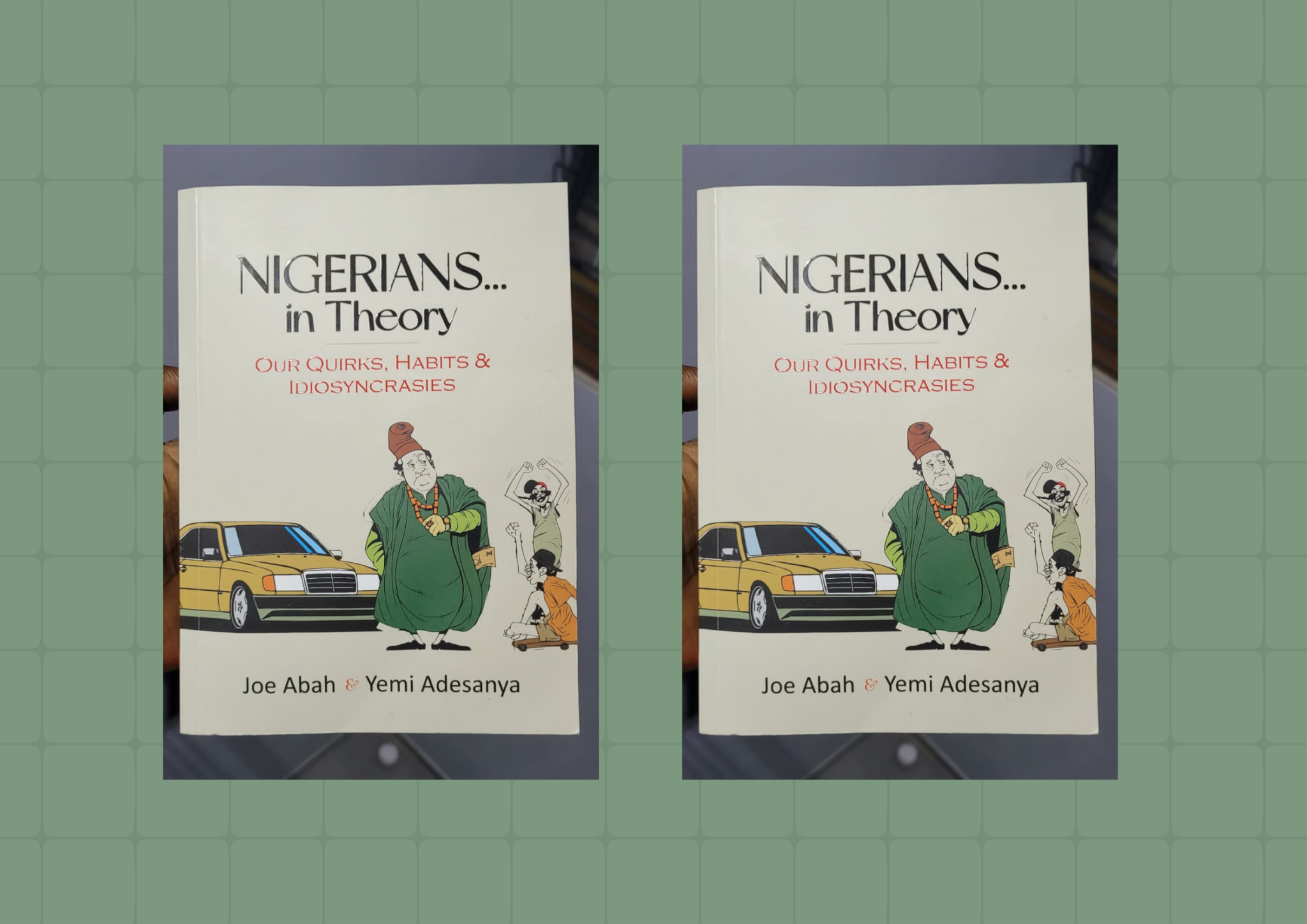

By merely looking at the cover of the book Nigerians… in Theory by Joe Abah and Yemi Adesanya, one might immediately place it within a certain tradition of Nigerian long-form commentary. For one, its sub-title ‘Our Quirks, Habits & Idiosyncrasies’. For another, its choice for cover art: cartoon characters illustrating the familiar scenario of the urban able-bodied and disabled in thrall of their cocky super-rich, perhaps a politician. Once in every decade or thereabouts, an author or two write on the social character of the Nigerian. Peter Enahoro’s How to be a Nigerian (1966). Mabel Segun’s Friends, Nigerians, Countrymen (1977). Victor Ehikhamenor’s Excuse Me: One Nigerian’s Funny Outsized Reality (2012). Elnathan John’s Be(com)ing Nigerian: A Guide (2020). These books deploy humour, candour and insight with varying degrees of success to show the quirks and quibbles of Nigerians in diverse sites of social interaction. Let us call this the Nigerian-explainer genre.

As those interactions migrate online, we are now provided with a rich chest of digital artefacts that could be mined to contribute to this national genre. Kole Ade-Odutola’s 2012 book, Diaspora and Imagined Nationality has noted the unique character of this digital context. ‘Cyberframing’ is what he calls the process by which the audience actively participates in framing the story. He credits the internet for being “a fertile ground for the harvesting of interpretations written by readers, who also double as writers”.

Odutola’s purpose was to mine the digital channels for the serious business of how the diaspora cyber-frames “Nigerian nationhood” using engagements in the pioneer USA-African dialogue chat room as resource. Nigerians… in Theory bestrides the old and new traditions in this genre. It treats the digital as evidence of the same Nigerian curious character that is best explored through humour, even while being equally suitable for interrogating how Nigerians debate “serious issues” (p. xvii).

It is not surprising that Abah and Adesanya turn to Twitter as the site for their prospecting. In the last few years, it has become possible to talk about a Nigerian subsystem on the micro-blogging platform—‘Twitter NG’—with its relevance to policy and politics so notable as to warrant the government shutdown of the platform, following the 2020 #EndSARS protests. Before those troubles, Joe Abah, one of the co-authors, had been a leading ‘influencer’ on Twitter NG. A retired civil servant in that all now too occasional mode of a true policy wonk, he daily teased out, by way of tweets, hypotheses which would have been worthy of debate propositions in a public policy class. And he did generate the debates, with his interlocutors straddling anything from the truly informed, genuinely curious and logical to the kind of loud twerp who may not know but is usually certain. It was often painful to watch how many of Abah’s ‘followers’, some of whom had been led by their own biases into believing he was a cheerleader rather than a sparring partner, fell in and out of love with him. Those who have missed his regular engagements in the last couple of years should now be pleased that their long wait has been rewarded with this book which collects many of those Twitter debates. For co-author, he has chosen the polymath Adesanya, one of his more thoughtful, “enthusiastic” debaters.

The book collects 170 thesis-tweets and analyses of the debates generated in their threads, all broken into eight thematic sections. The broad themes include Leadership, Economy, Politics/Governance, Religion and Family/Relationship. Majority of the tweets were Abah’s, some of them Adesanya’s and a few others by other tweeps. Sometimes the character analysis of Nigerians is encapsulated in a tweet’s proposition. An example is this tweets under Abah’s @Dr.JoeAbah handle: Anybody who calls you “Chairman” or “Excellency is about to beg you for money (p.7). At other times, it is borne out in the responses. For example, the tweet on the protocol of bribe-offering or -taking on p. 83 set off a debate on determinants such as rule of law, power relations and cultural attitudes, with many tweeps challenging the proposition that the taker would always initiate the transaction. In summing up, the authors noted that the answer could be a toss-up, having regard to factors within the micro-environment of the interaction, such as signalling by a potential taker, or within the macro-environment, such as cultural conditioning. In the end, they conclude that, regardless of the initial unwillingness of one of the parties, one successful exchange could reshape the expectation within that micro-environment and contribute to reinforcing the conditioning in the larger environment.

Analysis and conclusions such as these make for valuable policy lessons. They are the most original contribution of the book to the Nigerian-explainer genre. Not that the Nigerian character is always amenable to easy rationalisation, even when deploying complex tools such as games theory. Nonetheless, even behavioural sciences will admit an internal logic in the unique context of Nigerian social interactions by which ostensibly randomised behaviours could be explained. Not surprisingly, the first section of the book—‘Socialisation’—provides the best propositions for debating those verbal and gestural strategies that Nigerians deploy to work and outwit one another.

An example is in the “Chairman” tweet referenced above (not surprisingly, Ehikhamenor also treated this subject in a chapter of his book). In response to a proposition that the casual use of honorifics such as “Chairman” or “Excellency” in greetings by complete strangers is typically precedent to asking for favours, a tweep suggested that potential victims of such set-up would often beat their would-be violators to the game and call out an honorific first. This sort of game is only necessary in a society where the most casual interaction is expected to quickly establish a hierarchy and hierarchy establishes a system of patronage in which the receiver of an unrequested honour would be expected to pay for it. As even the authors counselled “you don’t want to be perceived as a stingy person.” Or as the artist Burna Boy observed recently while addressing the reputation of Nigerians for straight-talking, “we don’t lie unless we want to scam you”.

The foregoing being said, it is notable that not all of the propositions yield specifically Nigerian gold. An example is another Abah tweet: Decisions about what car to buy are often driven by emotions than by logic or rational thinking (p. 85). This is a standard proposition in behavioural economics. The section on ‘Economy’ is replete with tweets with propositions that are based on such standard theories of loss aversion (p. 99), diminishing marginal utility (p. 93), etc.

Nonetheless, even when they are universal, the debates yield insights with their own inherent value. One such insight is what looks like the incoherence in the Nigerian’s notion of corruption. For example, the debate on the casual imposition of patronage and consequent high-maintenance prestige system (conducted in the thread to the ‘Chairman’ tweet) did not much inform the explanation for what an interlocutor observed as the apparent elasticity of the appetite for wealth among Nigerian politicians (against the diminishing utility theory), or reflect in the thread to another Abah tweet: Givers are more likely to lack than stingy people (p. 102). One of the prolific interlocutors, tweeting under the handle @inpoco, also seems to conflate the culture of tipping in New York (p. 96) and extortion by public officers with whom she had to deal (p. 84), as examples of corruption. Indeed, it is peculiar that the American system shifts the burden for subsidising under-paid service workers directly onto customers. In fact, the role of business lobby in stagnating minimum wages in America may be regarded as a form of “legal and institutionalised corruption” facilitated by access money, as postulated by Yuen Yuen Ang (University of Michigan). In this case though, the business and political elite, and not the underpaid service worker, are the corrupt parties.

In another tweet, Abah almost has his finger on this problem of conflation. Stating that: The more you blame everything on corruption, the less likely you are to apply your mind to finding practical solution (p. 97), the authors however chose to sum up the debate in its thread by limiting it to how much excuse-making by government could really mask incompetence. On a broader level, when a society is so barraged as not to be able to tell what is corruption any longer, or to identify its forms, there is a real risk of desensitisation.

In the few last decades, the validation of the cultural context of development has required policymakers to put culture and values at the heart of their work. In the Nigerian case, the Nigerian-explainer genre should generally provide valuable reference guides. Abah and Adesanya’s 361-page book have now added to the genre and done more. Bridging the divide between the older titles in that genre with their entertaining prose, on the one hand, and academic forms on the other, the book would be useful for those looking at setting the cultural context of policymaking in Nigeria generally, as well as understanding the cyberframing of national discourse specifically. Those charged with national orientation would also be benefitted by the window which the book provides into how Nigerians perceive or argue for self, society, nationhood and the world.

Deji Toye is a Lagos-based lawyer, writer, and cultural advocate. He can be found on Twitter @dejitoye.