Among the genres, poetry is still king in the Nigerian literary space. It might not be hyperbolic to say a poetry collection or chapbook is published every other month. Last month, Facebook informed me of Bakandamiya: An Elegy, a new poetry volume by Sadiq Dzukogi. This month (December 2025) is the turn of Tares Uburumu’s Flora’s Love Colony. In 2025 alone, I wrote more than a dozen blurbs for poetry collections/anthologies. I am tempted to think that there is perhaps no nation in the world other than Nigeria where poetry – premier of all the arts’ majesties – is so flourishing.

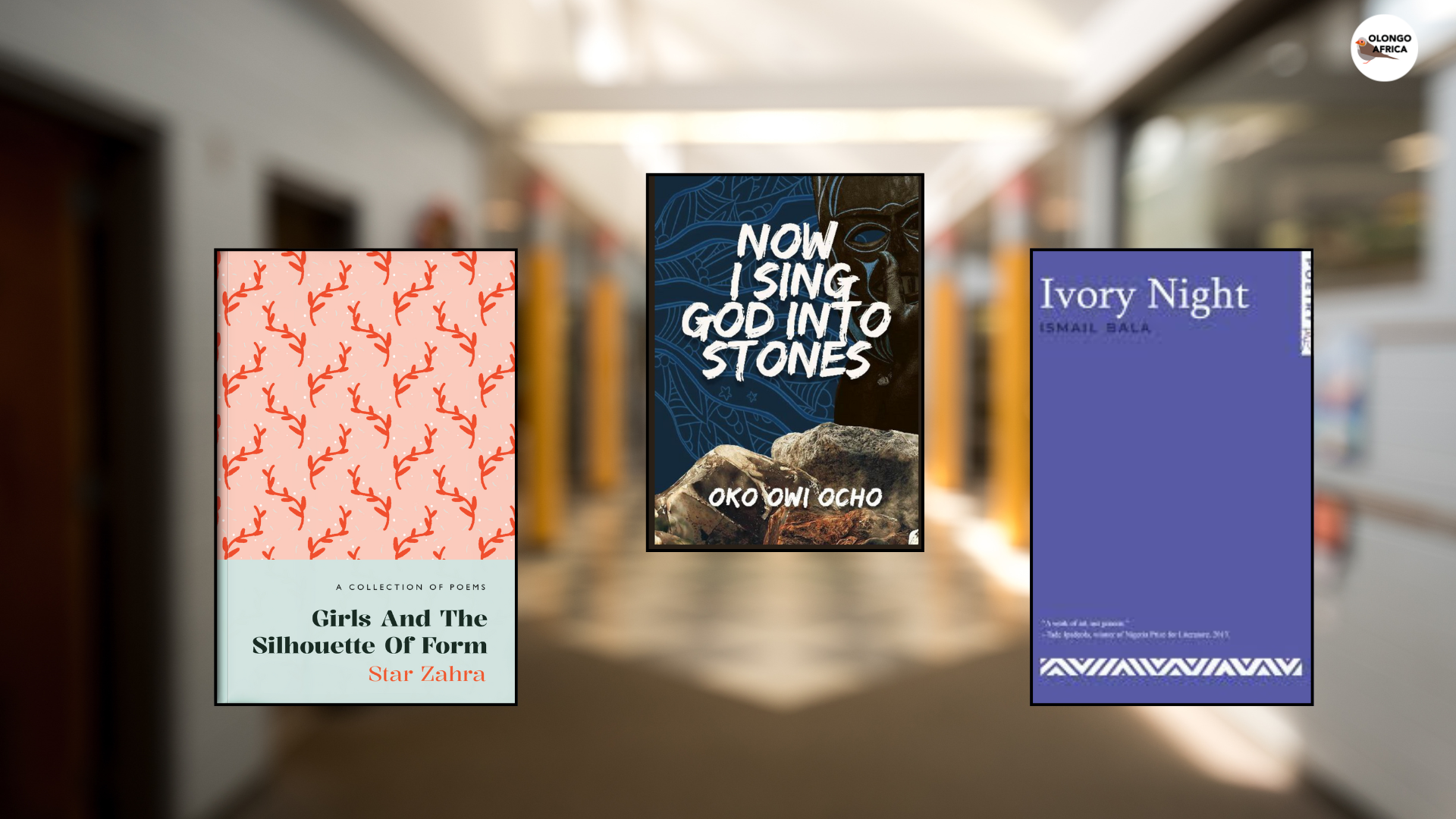

Three collections – which I read recently – have got me thinking of how Nigeria and its creatives rely on the poetic art – its metaphorical rhetoric – to make sense of what life can be in a society that fails to work. Or a society that gives so much of life (bad or good) to its citizens. These are Ismail Bala’s Ivory Night, Star Zahra’s Girls and the Silhouette of Form, and Oko Owi Ocho’s Now I Sing God into Stones. The titles are as short as they are long as they are metaphysical. Each is a second collection of the poet – actually what you might see as the pivotal sophomores of future solid voices, though Bala, in his midlife, is one whose voice has been there much earlier than those of Zahra and Ocho. The maturity of Bala’s voice is unmistakable. Ivory Night, published by Konya Shamsrumi, is in one-hundred-and-fifteen pages, with an introduction by Carl Terver, visibly entranced by what he sees as Bala’s magical language (tendentious as that sounds). Girls and the Silhouette of Form is of the Masobe brand – a seventy-three-page collection clothed with blurbs from some of the author’s best contemporaries: Soji Cole, Romeo Oriogun, Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto. Now I Sing God into Stones comes from the stable of Sevhage, has lengthy acknowledgements packed with numerous names, though it is the shortest of them with sixty-five pages.

Ivory Night is vintage Bala. That is, if you have been following his purportedly politically shy poems. On the surface, the poems are erotic, are about getting physical with emotions, are dramatic renditions of female-male entanglements. But limiting one’s gaze to the surface of these poems might suggest inadequate readings. Not many readers would have known that perhaps the best way to approach Bala, who lives and writes in a socio-politically charged Nigeria, is to zero in on his political positionality not to write about the obvious social dysfunctions of his society. Approached from this perspective, it would be clear that Bala does not, in point of fact, eschew socio-political issues, as he only relies on the metaphor of the non-political to teach us how to live and enjoy poetry in a socially dysfunctional society. It is a mark of incompetent reading to view merely what Bala’s poems appear to say on the surface without taking cognizance of the perspectives, contradictions, ambiguities, and ambivalences of which they are constituted. Bala may have made a great deal of effort in Ivory Night to purify his poetry of the smell of urchins in the streets, those without food and a bed to lay down their heads, those without the luxury of love and lovemaking. But beyond the surface of the elitist luxuries of heterosexual romantic performance, what I see in these poems is the overarching statement that love and lovemaking are part of the social dysfunction that characterizes life in our present society. Bala’s love poems, in other words, might be mirrors to those troubling social realities that most of his readers fail to see.

Thankfully, Ivory Night is not about poems that theorize love. Bala is not conceptualizing. He is instead dramatizing the interpersonal romance between heterosexual lovers. The persona at a point is a man addressing his female lover. At another point, it is a woman addressing her male lover. At once sweettalking and vulgar, clever and foolish, the male persona sees the female body, and the luxury space it occupies, as a place of escape from not only his society but also from himself. Take the “Swirl of Veil,” for instance, where the supposedly male lover has “returned in that drab Harmattan dust / to see my fate in your provocative eyes / and furtive swirl of your veil” (p.31). He escapes from the dusty Harmattan streets (of northern Nigeria) to the body of this veiled lover and can therefore exclaim at the end of the poem that “my world has been lush ever since” (p.31). To occupy this lush place, a body of a female lover, is itself a patriarchal act that should make us wonder whether this lover is indeed the ideal male lover. Which of course should also lead us to think of how male lovers take advantage of female lovers in our society where all kinds of exploitation – emotional, cultural, political – remain a way of life.

Relatedly, the female lover comes across as inadequate, conquered, in poems such as “The Beloved” (p. 90) where the female lover’s eyes, no matter how peaceful, will “tremble” in the presence of her male-lover. “Tremble” could suggest the utter submission of the female lover to her male-lover. But that is precisely where the problem is. Total submission amounts to – in what is mischievously miscalled pure, or genuine, or real love – vulnerability, especially in a world marked by greed and exploitation. The question: “what can you do,” repeated four times in the poem, when your male lover’s “hands touch / your lips / with roses” further stresses the helplessness of the female-lover in the presence of the male-lover. In another poem, “Yes, Go On” (p.91), the female-lover is characterized as one incapable of expressing herself under the spell of her male-lover. She is “caught like a spider on his glowing route” (p.91). Under such captivity, she starts a sentence that she can’t finish, which she eventually “lets slip away” (p.91). This male-lover, so endowed with the power to captivate, is not after all an angel but a mortal human in a morally complex society. In the next poem, titled “Him” (p.92), this male-persona “breaks, breaks” his lover’s heart and “jilts, jilts” the female-lover under his romantic captivity. In spite of his inclination to break and jilt, the female-lover – conquered by what some would call love, which is really all that love might not be – decides to give herself to him: “but I still stooped for him” (p.92). She goes on to confess: “I tried to entice him and he smiled / a big smile that wrecked me to bits, / but then I had been warned about him” (p.92).

The strengths of Bala’s Ivory Night lie in its capacity to use what appears on the surface as love and lovemaking to provoke us to think of our society, the contradictions of life, and the vagaries that surround the most powerful four-letter word on earth: love. The poems, in their dramatic cast, signpost the fact that the personal is social and the social is personal. And, yes, the volume is a delightful reading – indeed, top among the most delightful readings I have had in recent times. Bala’s poetic skills are demonstrated in ways that stand him out as one of the most sensitive poets of our times. His keen attention to the sensual zones of human physiology, to the physical surroundings, to the social dynamics, and to the interconnectedness of art and life endows Ivory Nights with a poetic maturity uncommon for a second poetry book.

And yet, the seeming individualism of Bala’s poetry, its rather unlikely subjects and tenors in the context of pressing social issues, plus its several foreign allusions have conspired to make his lyricism most likely alien to an average Nigerian poetry reader. This, in my view, is not something to praise as unique. A poet may choose to write only what he likes to read, but poetry – despite all arguments to the contrary – is a social art. In fact, it has the potential to inspire a social action.

*

Zahra’s voice is unmistakably feminist. She seems not to have patience for poetic circumlocution. The ease of her poetics bespeaks an art-woman assured of her maturing craft. There is something of mothering in her vision. She is keen about poetizing a world that would be safe for children, especially the girl-child. Her female personas are not, as we see in Bala’s poetry, conquered by – and yet pitiably submitting themselves to – the emotional empire of patriarchy. In her personas, there is the forcefulness of insisting on living even in the shattering weights of patriarchal, cultural, social, and political dysfunctions. And where her personas appear to lack the will to live, the poet herself invents the tenacity to live on their behalf.

The first poem of Girls and the Silhouette of Form, “What a Poem Knows about Death,” speaks volumes about how Zahra’s poetry is a witness – and proudly so – to what the girl-child, indeed every child, can face in a world where the tempo of reckless brutality is rising. The persona in this poem is not merely a child but one gifted with the use of “books,” “ball pen,” and “waist beads” (p.1), suggesting, as I see it, that she is creative. The “her” of the victim-persona is interposed with an “I” of what appears to be the poet-persona, whose rendition of this poem is a form of intervention to immortalize the “her” of this poem with a song. The brutalized girl-child of this poem echoes throughout other poems. From this initial salvo, it is clear that Girls and the Silhouette of Form is not a collection in which art is privileged over the human condition. And while not undermining the floweriness of poetic constructions, the collection achieves an admirable feat of brevity and punchiness, as each of the poems is startlingly straight to the point – though what is not said is often louder than what is said.

Zahra’s concern is not limited to the girl-child. Not, in fact, limited to children. Her concern for the vulnerable ones, for those trampled by powers, runs through the entire collection. She has a keen eye on the moral deficits of her country, so that, unlike Bala, she sees and feels and empathizes with the urchins in the streets, not in paradoxical ways. In poems such as “Of Bad News and a Country,” “A Tale of One City,” and “Wasteland,” the attention is on the hostility of the social space where girls, boys, and adults endure life. Zahra interweaves the precarity of living in Nigeria – or in any African social space – with the eternity of hope. The overall tone and tenor of this collection, in this regard, suggest that the gloom of life must not conquer the human will. In a poem titled “Hope,” Zahra waxes philosophical, speaking of how “Hope brings you to an island where you have to survive alone” (p. 19). And at the end, “You’d wonder at what point time sped past your vision / Unwavering like bolts of running seas” (p. 19). A running sea symbolizes the continuity of life, which appears to be the dominating idea of what I earlier described as Zahra’s mothering vision.

Life itself is marked in diverse poetic tenors with playful, often mischievous, poems that intersperse the heaviness of Zahra’s vision in Girls and the Silhouette of Form. Funny, even hilarious poems, such as “Why Happiness is Unpopular” and “Of Many Riddles and Other Things,” exist in this collection. There are also personal poems two of which are dedicated to her mentor-husband, Richard Ali: “Ugbede” and “Richard Ali”. Zahra says Richard is “a marble / Made out of sounds / Like loud waves wrestling against each other” (p. 38). Where waves wrestle against each other there are inevitably some conflicts. In the two poems, we see only one side of being a lover to Richard, emotionally. The other side is occluded. There are also poems about spirituality, even mysticism, about fear and freedom, and so on. Even in such poems, the social often overwhelms the spiritual and the personal. For instance, in the poem “Anjenu” (this word might be the Idoma translation of spirit), a father brings “pebbles and asked [his children] to kiss them for safety” in a place where “bullets landed / Right, left, everywhere” and the reality is that of “Living children carrying death on their heads / Like waterfalls retreating” (p. 10). The poem dramatizes the kind of mayhem, riot, or uprising that is too familiar with those living in Nigeria. The metaphors in this poem feel as surreal as the title “Anjenu” (if indeed it is the Idoma word for spirit).

Girls and the Silhouette of Form comes across as a potpourri of diverse musings, a mosaic of social realities, dominated by the fate of the girl-child, replete with the pronouns she and her. Form appears uppermost in Zahra’s mind, as the poems take different shapes with experimental exploits. From the prosaic to the pithy, the collection demonstrates the art of a woman discovering her poetic voice in the labyrinth of woven words meant to make us pity and empathize, search our consciences as humans, but also have a good laugh about a poet-persona who does not “know how to marry a man with / The meddling lyrics of a lone metaphor” (p. 27) in spite of – or because of – which she marries the brilliant poet Richard Ali.

While I admire Zahra’s thematic and contextual versatility, I have the sense that for her every scribbled emotion about anything can stand as a poem – and this point has the potential of watering down her craft. I recognize, of course, that a poet has a right to her poem. Except that as a reader I also have a right to a worthy, memorable Zahra poem.

*

If Bala so brilliantly dramatizes what some may see as love, and Zahra so effortlessly sings of the socially marginalized, Oko Owi Ocho emerges with an outpouring of the fire of mythopoeia. Myth, history, decoloniality: these constitute the frame that strongly shapes Ocho’s poetics. What he seems to me to be doing in Now I Sing God into Stones is to make poetically legible some of his obsessions with theories of Africa (the very idea of Africa as an epistemic enigma; or the colonial invention of Africa, à la V. Y. Mudimbe). In doing so, he hopes – I guess – to emotionalize the love of Africa, of motherland, for literature readers, and to return us to our roots, to our essences, to, in effect, decolonize our minds (to echo the Ngugian cliché). Ocho’s poetry, as it turns out, is an artwork that both excites and limits us in the way in which it arouses our feeling of indignation and empathy about those things we have lost to colonialism; at the same time it reveals our crass complicity in what the social scientist Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni refers to as the coloniality of power in Africa, as well as what appears to be the sheer incapacity of the present generation to even think of confronting coloniality. Now I Sing God into Stones is thus a collection that tweaks your feeling, shows you your rootlessness, offends your complacency, and teaches you how to be an African. Oh yes, the poems have something of a pedagogic arrogance about them: what with the pedantic stance, the intellectual pose, the veiled theoretical allusions, and the rather all-knowing I-persona.

The title poem “Now I Sing God into Stones” is exemplary. Words such as “god” and “history” and “mother” – ubiquitous in the collection – are key to understanding the nativity and past that Ocho seeks to recreate. Recreating the past, for this poet, is revisionism. It is also, in the strongest sense, anticolonialism. With such keen sensitivity, ideology becomes a powerful ingredient of his mythopoeia. A typical Ocho ideology surfaces early in this poem:

I rejected the crucifix when the priest, speaking Latin

& spicing Christ in harsh English vowels, asked me

to throw away my tongue

because it is shaded with the stains of my ancestor

because I sing water with melodies only memories compel. (p. 11)

The ideologically shaped poet-persona stands, first, as one who laments the history of colonial conquest that destroys his ancestral past, and second, as one willing to confront the present coloniality of being that privileges the “crucifix” – a symbol of ongoing colonization – over his tongue – a metaphorical reference to his folkways. Religion is critical to the colonial project, in the past and in the present. Africans, in my view, are at best as colonial slaves in their practice of Christianity and Islam, the two domineering religions rooted in colonialism. Hence, Ocho’s use of religious symbols and metaphors in this poem and in the entire collection. Hurt into writing the kind of poetry he writes (his “memories compel” him to sing the way he does), Ocho becomes an ideological poet-persona with a grammar of counter-discourse that sounds inspiring in some places and boring in other places.

There is something of the I-persona in Ocho’s poetry that troubles modern human rationality. This persona is clearly overwhelmed with the notion of self – split, disconnected, even inchoate. The self seems to struggle in a liminal space, pulled at once by what was in the past and what is in the present, as it implacably rails against its condition of disconnectedness. The persona’s experience of liminality is presented throughout the poems as a singularity that challenges what has come to be widely accepted as a complex of modern life marked by hybridity, decentredness, and ambivalence. Hear the persona here: “I wear the history of my grandmother / her shrine is an empty village. There are no worshippers / of the totem that she once cherished” (“I am the Boy Carrying a Village Grief” (p. 8)). As the title of the poem says, the persona (always an I, never a We) is stuck with her/his village’s grief. Not because the grief will not end, but because this ideologically charged persona is endowed with the moral agency to inhabit the space where she/he must perpetually interrogate the rationality of colonial modernity that undermines her/his ancestral modernity. This persona, in other words, is not like one of us eager to replace African-ancestral modernity with European-colonial modernity.

I am particularly enchanted by Ocho’s use of African natures (the plurality is intended) not only in this collection but in his other works, including his debut We Will Sing Water. Ocho’s poetic thought pattern is layered with natural beings (both seen and unseen: water, stone, tree, anthill, bird, sand, spirit, god, ancestor, etc) as either metaphors or personas. The context of natures – village, tradition as against city, modernity – emerges as something of a powerful motif in Now I Sing God into Stones. His dramatization of Idoma lore acquires concrete imagery in his representations of both physical and spiritual natures as an ideological forte for confronting colonial modernity. The second part of the poem “Rivulets We Carry from History” is vivid in this regard:

Inside room in Lagos, Bongos Ikwe

resurrects our ancestors with the metaphors of birds,

with a peck on every tree on the journey of leaving

they found the mouth of home & god

Otachikpokpo…

My pagan soul dangles between the jazz of Lagos street

& the alekwu chant in my ancestor’s mouth. Every

age finds an Idoma child chanting gods into stones. (pp. 9-10)\

With allusions, such as the one above to Bongos Ikwe’s folkloric music, and the evocation of ancient histories (Benin, Oyo, Kanem, Kwararafa, Apa, etc.), Ocho offers a richly historical and provocative poetics. His is an art that entertains, but also educates and provokes us to think of living with our past, to harness its decolonial potentials in a world largely veiled in neocolonialism.

Ocho’s second poetry book comes out stronger than the first. While his ideological positioning appears to be a strength in his poetic art, it might likely undermine his craft unless, of course, he improves on the skill of hiding ideology in the enchanting eloquence of strung metaphors.

*

Personally, I have enjoyed reading the three collections of poems I have reviewed above. I am, of course, likely to return to them again and again; to enlist them in my teaching schedules. They represent for me the varied character of Nigerian poetry – particularly from the northern region – in the present time. While it remains the most popular of the traditional genres, the case is also that poetry is the most abused by those derogatorily described elsewhere as ‘versifiers’ (and there are many of them in Nigeria). Perhaps the reason could partly be that while there are many writing workshops and literary festivals these days (where writers but especially ‘versifiers’ go to pat themselves on the back), there are incredibly fewer poetry critics on the literary scene.

E. E. Sule (also known as Sule Emmanuel Egya) is a poet, novelist, critic, and professor of African literature and environmental humanities at Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai.