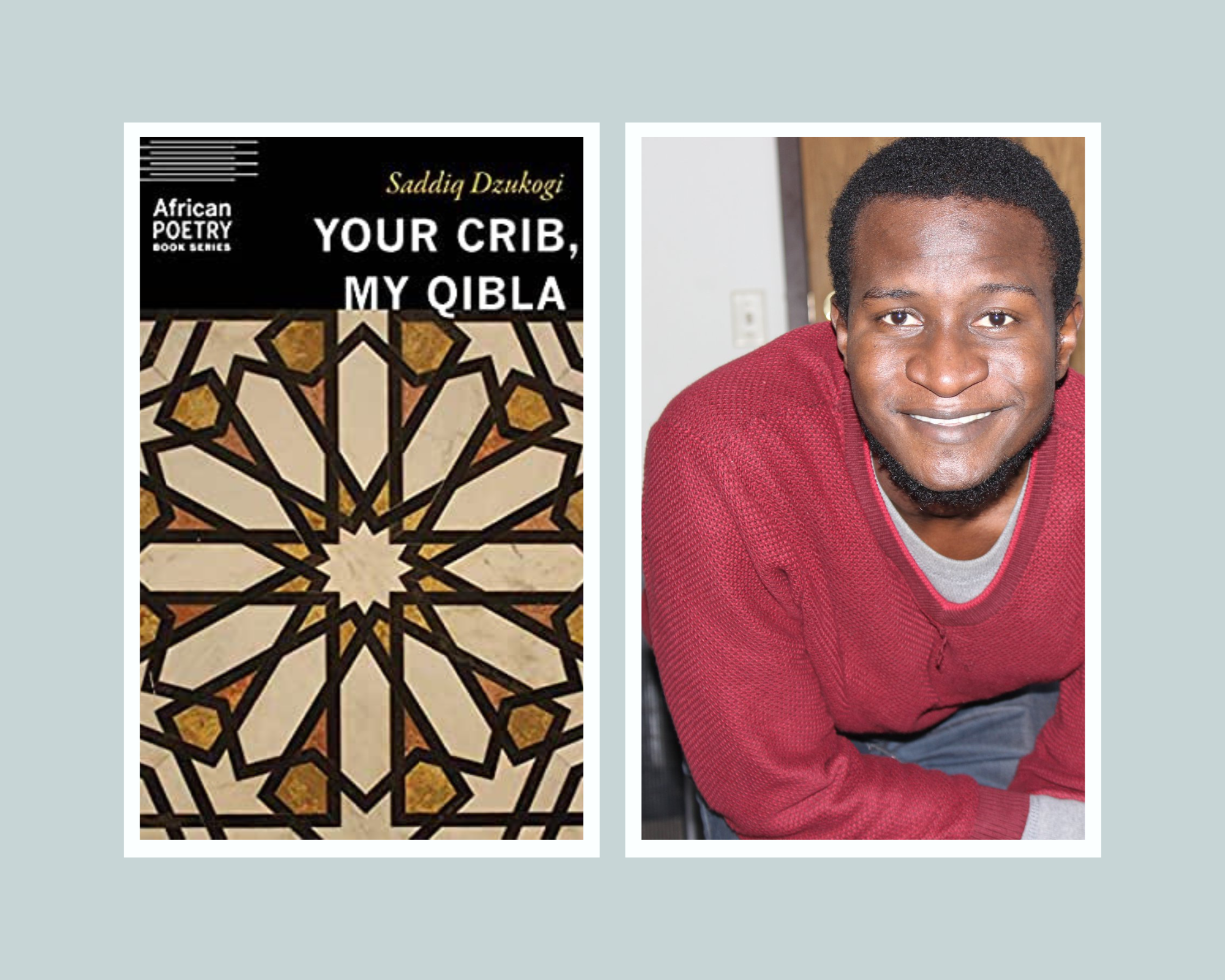

Saddiq Dzukogi is the author of Your Crib, My Qibla published under African Poetry Book Fund Series by the University of Nebraska. The book has been shortlisted for Julie Suk Award finalist and Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry shortlist in the United States. In this interview which took place in cyberscape across two continents, Peter Akinlabí, author of Pagan Place, engages him on the subject of grief and processes of mourning.

Congratulations on the short listing of your collection, Your Crib, My Qibla, for the Nigeria Prize for Literature. I understand it was similarly shortlisted for Derek Walcott Poetry Award and was also a finalist for Julie Suk Poetry Award. This is an impressive feat.

Thank you so much Peter, I really appreciate your kind words. And thank you too for your own poetry and for being a great example. I have learned immensely from your movement.

Let’s begin with the symbolic association in the title of the book: Your Crib, My Qibla. It seems to me that you are attempting here to connect the reality and the materiality of grief to the religious act of praying. Is it like that for you or does the conjunction represent a different metaphorical trajectory?

The title of the book underwent numerous metamorphoses. Ultimately this eventual title affords the clarity of the world of my grief and is evocative of the way the spaces my daughter embodied became sacred grounds where my tears and words made prayers and praise songs for her body, memories, and continued existence, manifested in lyrics that I created. And you put it quite succinctly. There is a certain vagueness to grief, a slippery language that is ever present in the consciousness and unconsciousness of thought, yet also elusive to expression. I found this strikingly universal. What I intended was to find an expression that can contain the nebulousness and materiality of the grief that was roosting, and still roosts, in my heart and body. In my mind, a kinship exists between this language and the language of my prayer, and indeed prayer itself. I struggle, in prayer, to speak to God of my aspirations, to speak of my deservedness of kindness of his gifts, ones I already have, and ones I request. It is all an act of fate, that all will materialize in some ways, whether to my understanding or by some divine machination. This poetic exploration relied heavily on insights I have gained, over the years, from my oeuvre as a poet, so yes, the title represents this metaphoric trajectory that collapses the meaning of things into a giant blur of uncertainty that questions both my being and often faith in the world, and beyond. The title irreversibly represents a new site of worship, a place to nurse the imposed wounds of grief, a place of memory where there is more than just a symbolic gesticulation to memory but also a spiritual connection to experiences that are lived and imagined.

It is perhaps that vagueness to grief that circumscribes the language by which we express grief. The somber beauty we find in elegiac writing necessarily occludes lucidity. This is perhaps because an attempt at delineation of a foundational emotion such as grief which links us to existential questioning also leads into a different level of abstraction. Your book reminds me of Joan Didion’s Blue Nights in that sense, a memoir in which she wades through the loss of her daughter. Perhaps looking through these poems after writing them, do you sense – as I do – a process of questioning in which you are plumbing the complex and unrevealing order of the cosmos to find some sense of meaning in Baha’s glorious appearance and unexplainable disappearance?

There is a lack of clarity that befalls a grieving mind, it would seem. Grief is a reedy veil of fog that is indissoluble in the heat of even the body’s discernible pain. It has the potential and every intention to undo its victim. We are always gesturing towards meaning, towards articulation as poets, as humans, and I feel this spirit we imbibe so rigorously in our daily pursuits. The emotions from loss, and its many iteration teethers the mind to the language of abstraction which I consider a concrete articulation because, in this and several instances, it is a language, perhaps, one moved by lyric, by the kind of sense and understanding we get from music, even when the music is in a language, we ourselves do not speak, or comprehend. I am reminded of the fellowship of agony my wife and I shared, in the early days of the loss of our child. She understood the language of my silence and the world of pain that it contained, and I understood the language of her lamentations even in the absence of words she was afraid to speak. We were bound by our unique understanding of our unvoiced emotions in ways that we, too, did not understand. But what I have now is this artefact of Baha’s existence. You will think that I engage with it regularly. But I find it hard to read. Very hard to read. I am met with the realization of her death repeatedly, each time I do. But also, I am reminded of “Baha’s glorious appearance” and not much of the disappearance. I always say quietly that she did her job, planting a luminescent light in my eyes and in my heart. And this commemoration is what remains of her body, and life.

Your Crib, My Qibla focuses on the death of your daughter, Baha, which occurred in 2017. But throbbing throughout this book, five years later, is an intense, unyielding presence of her loss. Everything seems to reverb her vivacious subsistence; and the words in the poems move in unfaltering riptides to these reverberations. This makes me wonder: does it ever get better, even with setting memories down in writing or any other form of commemoration?

The unyielding aspiration of the book is to perpetuate her existence even after being swallowed into the bowel-void of death. I wanted to preserve her, so the world would continue to be acquainted with her. I wanted her name even in the mouths of strangers. This I have done, the consequence of which is that this memory is salt to my wounds because as a poet, the expectation is that I must also read these poems to other people at public events, to be exposed to them with all the feelings that I am yet to fully understand. To be vulnerable, in such a public way, takes a toll on me. But this is the contract and the sacrifice I bare for forcing her continued existence, albeit in the world of my memory and the book. It doesn’t get easier. It gets better in the sense that I am better at carrying this cross. It is now light as opposed to darkness. I mean, I often find myself in the dark creeks of grief, but I can row myself back into the light, a bit faster now. I attribute this agency to the book. It reminds me of her in ways that rebels even against time. Grief is a violent memory of our departed loved ones but forgetfulness is a far more violent beast. I want to add that it is humane of you to let me know the potency of my aspiration, five years on.

Yes, yes, your tribute is as singularly beautiful as it is unbearably sad. And as you have hoped, Baha indeed belongs to the canon now. Meghan O’Rourke once said “one of the hardest things about a death is recognizing that the person is actually dead”. And I imagine that any form of commemoration, including writing, is also a stage in the process of reckoning, a stay, as she puts it, against dread and chaos. For you, did the decision to write arise from that recognition or was it the very act of recognition?

Thank you so much, Peter, you are very kind. I think it was both. I rely on poetry for meaning. It has enriched me with a profound understanding of not just my own life, but my world too. When things are unclear, I turn to its light and wade through, out of the darkness of uncertainty. Within that quiet and often noisy chaos of grief and loss, I return to my organic way of being, of understanding. It was never my intention to write a poem or even a book, but what we have is the scrapbook of those moments, an etymology of my grief, documented in a form of meaning-making I have come to trust to offer meaning not just to others, but most importantly, to the self.

Would you comment on the use of the third person narrator in the first part of the collection? Does it have any particular technical significance?

Yes! It is a tough book to read. On one level it creates distance between the reader and the experiences. It may seem like relinquishing agency of one’s own feelings, but it was an artistic choice to make it a little bit easier to read without forcing the reader to embody the pain in a way that will feel so personal to them. Also, the structure of the book is such that it crescendos in a dialogue between me and Baha. That third person voice has an omnipresent view which presents the poet as also a witness and experiencer of the progression of his process.

Grief is an intensely isolating experience; it creates its own apartheid in which the mind is, often abruptly, excised from the outside world. But, as some of the experiences you recollect in this collection show, there is a context – which I suspect is distinctively African – in which family members become co-travelers in filling the body of void that sits in the mind of the one that grieves. We see this, in this collection, in the crucial interventions of Mother and Grandmother, who read and redirect the signs of your sundering, and interpret the wraith appearances of sorrow by ways of culture and faith. How do you estimate these interventions in the overall experience of healing?

I mean, healing is an expectation that I suspect is not attainable. What it means to heal for me is to forget. And forgetting is a luxury I do not want to be able to afford. I think of grief precisely the way I think of a wound on my skin. And maybe for some people the scar, the retained painless clot of mass is what healing is. For me healing is the absence of wounds and scars. Meaning healing is the ability to hold my daughter in my arms, to see her grow and become the wonderful woman that I envisioned her to become. If I have a memory and a father’s aspiration towards his child, then the question of healing does not arise. Every year without her is a different kind of wound. She would have been six years old in a few weeks’ time. Her birthday is November 22nd. That is a wound that is yet to happen. One that lies in waiting for me, in my future. There is no healing for me. And if I am being honest, I do not aspire to it. Because to heal is to forget. In a weird way, the pain in my chest, the hole in my heart is how I measure the love I have for her. I do not understand this presage. But the pain of that absence is her presence in my world. And even though it breaks my heart, it is a heartache that I rather keep. It is how I can express my love to her. It is the only language that I feel like she will understand. It is the way that she continues to nourish my own life in the absence of hers. I do not know if this makes sense to anyone else, but it does to me. I particularly like this question because it allows me to speak about the other women in my life. My Umma, and Ba’aba. I have gained a lot of wisdom from their lives. And you are right, in the thick of grief, they offered both prayers and advice on how to be in the world. But grief is a lonely road that is travelled unaccompanied, even if you have comrades who have lost the same thing. It is just a different journey all together even if you share the path with others. There is a critique of both culture and faith in the poems, specifically pertaining to how men must grief, how the bereaved must accept the viciousness of losing an endeared one. We must remain unseen, our emotions buried under the sturdiness of our masculinity. Well, I am a very sentimental and sensitive man. My emotions are worn all over my body. My pain, my joy—everything. My feelings are all reachable without much prodding. I often joke that when you reach to touch me, before even getting to my skin, you will, my emotions. I craved so much quiet, because most of the people in my life wanted me to be more of a man I never was. Not to cry as much. Not to feel as sad. Not to not to not to…So I perfected the art of living in the rapturous chaos of silence, and tears. Bob Marley’s Three Little Birds was a song that broke my heart even further. A song that broke me further and attempted to mend me back. The poem “Waterlog” speaks to this intervention you speak of. I was taught every mantra of vigor but my defenselessness against my sorrow meant my daughter could reach me. I truly believed that, as I still do, today.

In “Learning about Constellations” you write: “Baha is not dead—she is walking her way into myth”. Although, in context, that line relates to how the living imaginatively sacralise the procedures of passage, hoping that ritualistic gestures, such as entombing milk, may suture our hearts to the great unconscious of the beloved departed. But when we write about people we have loved and lost, when we construct a lasting artefact to their memory, we do not only memorize them, we also weave a mythology of presence about their absence. Was that how you felt writing about Baha?

You articulate it gorgeously; I hope my response can cope with the beauty of your enquiry. But yes. I sometimes suspect that imagination is a more compelling occurrence than reality. A well-constructed realm of imagination will provoke a genuine reaction, which is an experience, and that makes that world real, but an experience that conforms to our appeal. Similarly, there was a painful gratification that I felt after writing that poem. It is one that I find the most difficult to read. I felt her aura, in a way that is profound and real. When I started the book, I just wanted to translate the distinctively personal dialect of my grief. I wanted to reach for meaning beyond the fogginess of that moment. I wanted an audience not just with the memories of my child, but with whatever manifestation of that child that I was afforded. I wanted to experience that which death has threatened to sever. Indeed, it was a ritual for me, to quieten the noise of my world so I can hear the voice of my child within the bounds of her ethereal universe. The poems were just the portal enabling that connection and the book itself is a reverie of both our experiences; mine and hers.

There is a sequence of poems in the section “My Qibla” in which you invest Baha with agency to speak, but also agency of imagination. Here she does not only console her father, she participates in the grieving procedure and in the disputations about life and loss. Being on the other side of the veil, our own imagination assumes she knows and sees more than we can, thus we trust her omniscient eyes. As literary devices go, does making Baha a speaking voice make certain kinds of perspectives possible – e.g. the nature of the ethereal experience–which would have eluded the language of the grieving “he”?

Often, I imagine that humans are so engrossed in their own affliction that they fail to see or hear. I too am guilty of this blindness. But the poems you talk about allowed me to see beyond memory, beyond the folly of my own knowledge. I imagined that the afterlife is lonely without one’s dearest. I recognize death to be a one-way flight, out of this world. With distance comes a level of intelligibility that proximity cannot beget, that omniscient eyes. I think each time we think of a story that involves us, we may fail to acknowledge that there is more perspective to what we perceive, that here, even the dead can speak, and we would hear if we listened, through memory, through our own imagination of them. I think it was an important moment in the book where Baha begins to speak after the foreshadowing of the first section in the voice, I like to call the poet’s subconscious, leading to that dialogue. I think a book of poems should always thrive to do more, in terms of its overarching story, outside the individual objective of each poem. But to answer your question directly, I wanted to dream about her. I wanted to hear her, in whatever probable form. This was the only form that could manifest my desires.

It has been a rewarding experience speaking with you, Saddiq. Thank you very much.

Thank you so much for your insightful questions and taking out the time to read the book. Thank you, thank you.