by Tade Ipadeola

When news broke late on 22nd April 2022, that Ọba Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí III, the Aláàfin of Ọ̀yọ́, had joined his ancestors at the ripe old age of 83, there was a sense in the entire Yorùbá speaking world that a truly regnant king had departed the realm.

Ọba Adéyẹmí was born on October 15, 1938 into the Alówólódù Royal House of Ọ̀yọ́. His father, Prince Raji Adéníran Adéyẹmí, was later enthroned as Aláàfin in 1945. His mother, Ìbírónkẹ́ of the Epo-Gingin, Òkè Ààfin moiety of Ọ̀yọ́, knew her young prince was a potential Aláàfin, as did the father. The parents ensured that their offspring had Yorùbá court education (in the court of the Aláké and in Ọ̀yọ́) as well as Western and Oriental (in Arabic) education. The young Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí would also be educated in the ways of Yorùbá aristocracy in the Lagos home of Sir Kòfó Àbáyọ̀mí and his Lady, the singular Oyínkán Àbáyọ̀mí. This is another way of saying that young Adéyẹmí had some of the best preparation possible at the time, without leaving the shores of Nigeria.

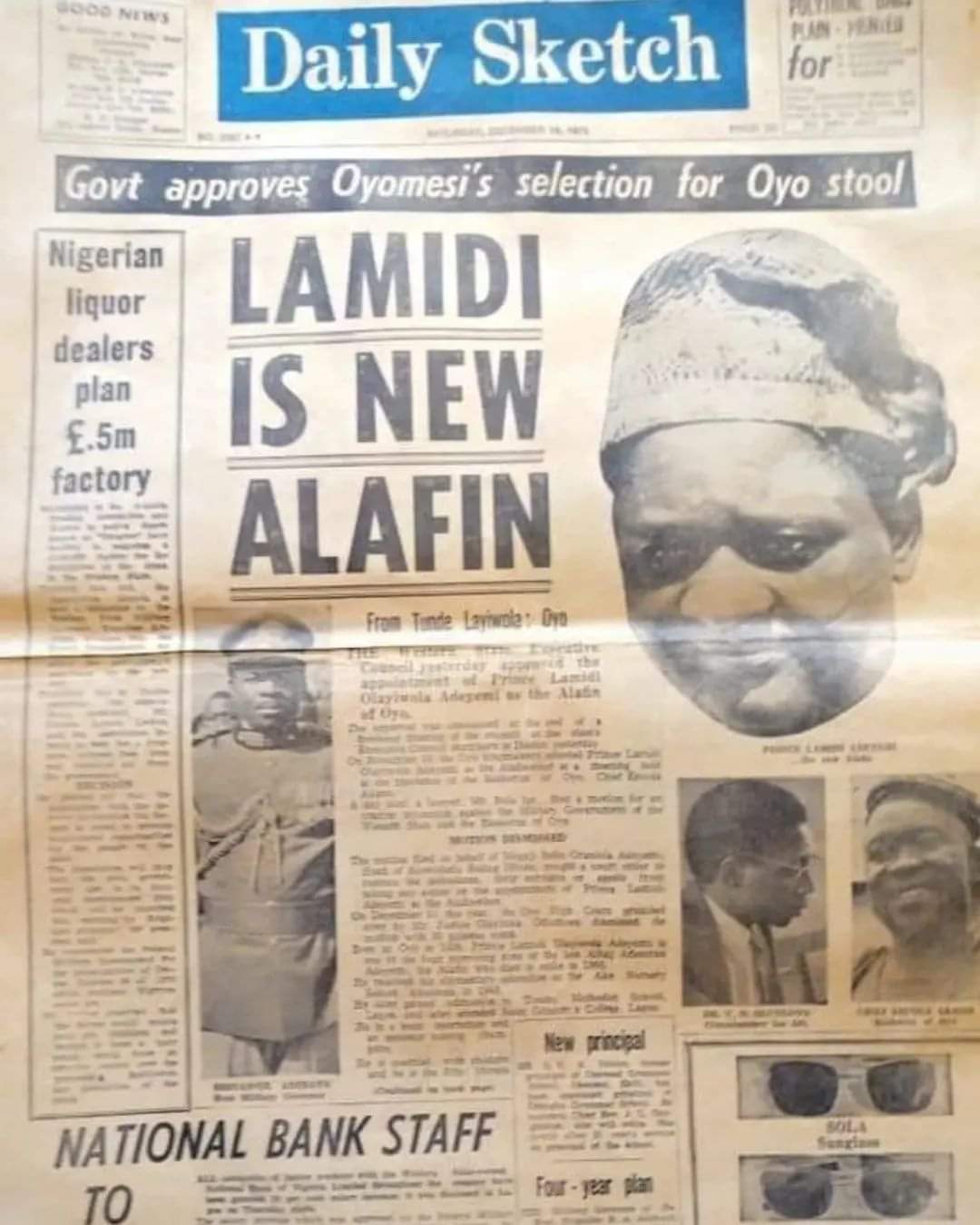

Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí was crowned king in the wake of the cessation of hostilities in the Nigerian Civil War on November 18, 1970, at the age of 32. A young king, he quickly asserted himself in office and forged alliances all across the country that would consolidate his power and royal influence.

Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí displayed a deep capacity for the history of his people from a young age. Gifted with above-average facility in both Yorùbá and English languages, he would learn and occasionally deploy the discipline of writing in causes he pursued. There was also on occasional display his firm grasp of mathematical principles.

His mind was educated in a way most fitting for a future occupier of a throne that had a history of a thousand years of both open and covert warfare behind it.

Though knowledgeable in the traditions of Sufi and Sunni Islam, and though well tutored in Protestant and Catholic traditions of Christianity, his origins in Ṣàngó traditional religion never faded from his consciousness. A master interpreter of the talking drum, he would often trade insider jokes with his talking drummers. He was also a graceful dancer of both dùndún and bàtá music.

Ọláyíwọlá Àtàndá

Ikú ọmọ ikú

Àrùn ọmọ àrùn

Ikú bàbá yèyé

Aláṣẹ èkejì òrìṣà…

There were three years of contestation for the Ọ̀yọ́ throne between the passing of Ọba Bello Gbádégẹṣin Ládìgbòlù in 1968 and the ascension of Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Àtàndá Adéyẹmí in 1970. More than his co-contestants however, Ọba Adéyẹmí was prepared for palace intrigues as well as the subterranean moves that are usually made during interregna. Ìbírónkẹ́, his mother died young. Aláàfin Adéníran Adéyẹmí, his father, lived into his late 80s, dying in exile in Lagos in 1960 after having been deposed by the Action Group government in 1955. To have somehow survived both these handicaps points to astute politics as well as more than a little help from friends.

His friends were many and included Ààrẹ Aríṣekọ́lá and Chief Samuel Akíndélé, both of whom predeceased Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí. Ààrẹ Aríṣekọ́lá made sure that the Aláàfin arrived in style wherever he travelled. They both had a specific taste in cars. But this was just one aspect of their friendship. They also shared religious discourse and Aríṣekọ́lá helped his friend when he came under heavy fire from the fiery Yorùbá poet, Ọlánrewájú Adépọ́jù. Adépọ́jù, one of the finest poets in the Yorùbá language, embraced a strict form of Islam and began whipping up caustic verses against the Aláàfin for what he deemed as Adéyẹmí’s lax approach to Islam, especially after Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí had performed the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. In an album Adépọ́jù waxed on the subject, he framed the issue thus

“Ó lọ (Mecca)

Ó bọ̀

Ó tún ń b’ọ̀rìṣà”

These charge(s) of backsliding and syncretism were not products of a mere tiff. The poet waxed exceedingly eloquent during this period but to the credit of his Yorùbá audience who took things in stride, the matters never got out of hand. I was a pre-teen at this time but even I could sense the tension between them generated by the iconoclastic poet dangerously drenched in monotheistic zeal.

Chief Samuel Akíndélé on the other hand was a Lord of the Yorùbá language as well as a consummate grassroots politician. S. M, as he was popularly known in Ọ̀yọ́, was regularly summoned to the palace just to josh with the king. S.M was a deep-dyed Awoist and there wasn’t much common ground politically between himself and the king. But Aláàfin Adéyẹmí’s love for the Yorùbá language was such that he had to joust from time to time with the best speakers of the tongue. The Commonwealth in the language demanded maintenance and Ọba Adéyẹmí would not be found shirking. He often said publicly:

Aìwà ká má l’árùn kan lára

Ìjà ni t’Ọ̀fà

Ìpánle ni t’Ìjẹ̀ṣà

Ẹnìkan ò mọ oun ará Ọ̀yọ́ ń wí.

Such revelling in ambiguity, the double entendre, the linguistically elliptic, the thoroughbred paremiological as well as the post proverbial, acknowledged as a cherished congenital condition, and for which non-Ọ̀yọ́ people constantly deplore and vilify the Ọ̀yọ́ as indicative of a slippery character, is only ultimately solipsism of a playful kind. The Ọ̀yọ́ love the ayò game. Their dialect is verbal ayò. It is the precision of a certain order. A precision that is almost mathematical. For anyone nurtured in the court environment, it was a necessary skill even if an annoying one for bystanders.

Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adeyemi made friends even with people his upbringing taught him to regard as commoners. He made friends with these people even when he knew that they had strong republican inclinations. One such dynamic which I observed at close quarters was his relationship with my late father, Àyántádé Àtàndá Ìpàdéọlá. My father is from the Jagunṣàngó clan of Akínmọ̀ọ́rin and an Àtàndá by oríkì. So there were two things they had, ancestrally, in common. But dad was also a well-known stalwart of the Action Group. Nevertheless, over a period of a decade and a half, Aláàfin Adéyẹmí persuaded him to accept the title of Akínrọ́gun of Ọ̀yọ́. They would normally write in longhand to each other or, when the issue was serious enough, type their mutual messages. My father didn’t like going to the palace but whenever his absence became noticeable, he would receive a terse message usually in the form of a question: are you still my Akínrọ́gun? Or, are you still my chief?

The man can read, my father would say, whenever I felt a document he was about to despatch to the palace was too long. This happened quite often during the bid for a separate Ọ̀yọ́ State from Ìbàdàn State circa 1996. Coming from my father, this was high praise indeed, for he could be a snob. The two seldom agreed over anything. When I wondered aloud about what the point of it all was, my father would say he is the southpaw sparring partner of the king. The king didn’t appreciate those who always agreed with him much. Or those who, like the king, were not a natural southpaw.

Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí was a boxer by instinct as well as in practice. You’d rarely catch him with his guards down and he picked his moments to jab even as he bobbed and wove. If you know Ọ̀yọ́ well, you will understand why a lot of boxers seem to emerge from the town. It’s a pugilistic mystic in the air and the grand patron was the Aláàfin himself.

As broached earlier, Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá received the traditional education reserved for royals and the priesthood in Yorùbá culture alongside Western education. As a boy, he was entrusted to the care of the Aláké of Ẹ̀gbá, one of the brother kings of the Aláàfin. It is as if a prince of Sparta was entrusted to the king of Athens for courtly education. There is a parallel in the old ways of training the babaláwo. Those born into the savanna parklands of northern Yorùbá country and who began their training there often did postgraduate training and research for up to seven years in the forest belt. Advanced post-doctoral studies and research was available in the coastal portions of the land. This way, prospective kings and priests were thoroughly familiar with people, flora, fauna from a really expansive geographical area.

This point bears reiterating because there is a modern but mistaken notion in certain quarters that the Yorùbá only became Yorùbá when invaders came into their country. This is not so. The sons of Odùduwà know who their brothers are. They do not always maintain amity and they have even succumbed to predatorial impulses against each other sometimes but the Yorùbá know themselves in the way full brothers and sisters know themselves.

*

In January of 2013, at the peak of the harmattan, the Ọ̀yọ́ palace suffered an inferno that gutted more than 20 rooms together with priceless artworks and artifacts. The fire was traced to a faulty PHCN transformer. The damage to the Ààfin was extensive. It was one of the very rare occasions in which the Aláàfin was visibly broken. He did recover his composure and the palace underwent reconstruction but irreplaceable works were gone irretrievably. Rumoured to have been lost in the inferno is a drum from the mid 16th century reputedly made with human skin much as the cover of De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the Fabric of the Human Body) by Andreas Vesalius in Belgium, published at about the same point in time in history. Whispered were words that implied some anger from the gods toward the Palace, words that suggested that the loss should be regarded as good riddance to a barbaric past.

But there are other ways to view the loss of these artifacts, even those, like the cover of the treatise of Vesalius, that had a difficult and cruel narrative behind them. How is it, for example, that the human imagination in the European lowlands and in the African parklands coincided such that two knowledge-bearing objects were deemed sufficiently finished only when human skin was pressed into service? If one locus had done this without concurrent and similar action in the other, wouldn’t historians have deemed that locus intrinsically depraved? Like Ilé-Ifè, Ọ̀yọ́ had these histories and the appointed guardian is the monarch whose duty it was to preserve. The fires did much to deprive future generations of closer study of these artifacts. For a known history buff therefore, the fire of 2013 was hell.

Other fires the Aláàfin had to put out were man-made. There was the fire of Governor Adébáyọ́ Àlàó-Akálà who threatened to dethrone Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí. Considering the history of the Alówólódù Ruling House, Ọba Adéyẹmí had to do all he could to ensure that the rumoured dethronement did not happen. Governors in the notionally Federal Republic of Nigeria wielded enormous powers and can dethrone kings if they themselves feel threatened. To douse the flames of the threat, Aláàfin Adéyẹmí embraced Akálà’s challenger, Abíọ́lá Ajímọ́bi. It was a risky thing to do but fortunately, Ajímọ́bi did win at the polls. Saved by the bell. But in the way that the romance between traditional authority and the occupiers of office in the modern state sours, Ajímọ́bi as Governor soon began to have wonky ideas about innovation in the traditional structures of Ọ̀yọ́ State. The first experiment was in Ibadan. The next and scheduled stop was Ọ̀yọ́. Aláàfin Adéyẹmí knew just how dangerous it could be to tinker with these time tested structures and so diplomatically withdrew support for the revisions to the Chieftaincy Laws of Ọ̀yọ́ State. The Governor was not amused but the monarch knew things that the birds of passage in government did not. It is a terrible thing to have men in power who could not be warned. The Ajímọ́bi inspired Chieftaincy legislations are all being revisited now but it took the sustained covert campaign of Aláàfin Adéyẹmí and the overt opposition of the Olubadan of Ibadan at the time to halt the misguided experiments.

But by far the darkest pall to fall on the reign of Aláàfin Lamidi Adéyemí III descended in November 1992 when the charismatic Aṣípa of Ọ̀yọ́, Chief Amuda Ọlọ́runòṣebi was murdered with extreme prejudice en route his farm. The whole of Ọ̀yọ́ town and indeed the State went into shock. The police made arrests but no one was charged or convicted. Undeterred, the family of the Aṣípa brought their grievances before the Oputa Panel which the Federal Government had instituted to examine human rights violations all across the country. The Aláàfin’s response was to apply to the Federal High Court to restrain the Oputa Panel from looking into the matter. This was the first time the Alaafin would formally respond to allegations of any involvement on his part in the murder of the high chief. The Oputa Panel refrained from examining the petition of Ọlọ́runòṣebi’s family indefinitely. No other Aṣípa was installed in the lifetime of Lamidi Adéyẹmí. A significant quarter of Ọ̀yọ́ town, particularly Ìsàlẹ̀ Ọ̀yọ́, held grudges against the Aláàfin until the last. They have a pending petition before the International Criminal Court.

*

Ọba Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí’s birth and ascension to the ancient throne of Ọ̀yọ́ occurred long before the age of social media. The transition of the monarch into the realm of the ancestors, however, occurred at a time when news travelled around the world in mere seconds through social media. Many millions learnt of the departure of the king before the traditional protocols put in place by Ọ̀yọ́ could even take the initial steps of breaking the news. As at the time I’m writing this obituary, the earthly remains of Aláàfin Àtàndá Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí III have been laid to rest in Bàrà, the traditional necropolis of all Aláàfin by Ìṣẹ̀ṣe practitioners of Yorùbá religion. There were Islamic prayers by the Imams and the clerics over the remains of the Aláàfin earlier on the 23rd of April. There were even initial reports of the king’s burial according to Moslem rites all of which were debunked by the Ṣàngó and the Babaláwo priests who took over the funeral arrangements as well as the remains of the king.

Why was there the thinly concealed standoff between the Islamic clerics and the traditional Ìṣẹ̀ṣe practitioners? The annals of the Yorùbá places the Aláàfin in a prime position, as a coeval of the Ọọ̀ni of Ilé-Ifẹ̀, among the descendants of Odùduwà. The Ọọ̀ni saw to the spiritual welfare of all Yorùbá people while the Aláàfin saw to their military defence. Indeed, Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí III installed not one but two Ààrẹ Ọnà Kakaǹfò in the course of his reign. These functions were not to be moderated or accentuated by personal beliefs or lack thereof of the kings. It was considered spiritual atrophy to yield either the selection or the interment of a Yorùbá king to any other person or persons apart from the Onìṣẹ̀ṣe. For good historical reasons, the Yorùbá have treated all other religious beliefs apart from their own with suspicion when it comes to the beginning or end of a reign. The collective cultural investment in the wisdom of Ifá would be for nothing otherwise.

Antonio Gramsci, the philosopher, observed that moments of transition, interregna, are dangerous times because otherwise surreptitious forces are liable to bend the course of history, sometimes grotesquely, their way. Even though his observation was made in the specific context of class struggle, it is true nevertheless of culture clashes.

Aláàfin Ọláyíwọlá Adéyẹmí III has gone on to his ancestors now and the Yorùbá resolve to maintain their identity has withstood another test. Yet, entropy, like rust, never sleeps. Eternal vigilance is required to keep the deep hulled vessel of the Yorùbá culture afloat in the sea of the 21st and future centuries. Long live the people.

_____

Tádé Ìpàdéọlá, a Nigerian poet and lawyer, was born September 11 1970. He has three published volumes of poetry – A Time of Signs (2000), The Rain Fardel (2005) and The Sahara Testaments (2013) to his credit. He also has other works such as translations of W.H Auden into Yorùbá and Daniel Fágúnwà into English. His collection of poems Cold Brew, is due for publication in September 2022. He is also a past president of PEN (Nigeria Centre). Ìpàdéọlá lives in Ibadan, Nigeria, where he writes and practices law.

Cover photo from IntelRegion