Nollywood is the trash’s last leaves, claims Kenneth Harrow in the last chapter of his seminal book, Trash: African Cinema from Below. Among its audience and even in academic circles, most Nollywood films have been critiqued as trash-coated with dry dialogues, melodramatic moments, and poor cinematography. Many of these discussions about the poor vision in the films retrace this foundational failure to aggressive commercial pursuit of the producers. Yet, Kúnlé Afọláyan has been celebrated in Nigerian cultural scene as a face of renaissance in Nollywood one whose movies cannot be categorized as low-grade. He is what Jonathan Haynes vaunts as an emblem of New Nollywood. With Harrow’s disaggregating insights, trash takes on multiple contexts for class, gender, and other immaterial dimensions; even the sloppily plotted films have their regimes of value, says Harrow.

Of course, Kenneth’s discourse on trash comes with a backlog of weaknesses. One is that it maintains subtly the idea of impurity and that is often associated with femininity. This sometimes makes its application problematic. That is, if one fails to see how it opens a gendered episode in which women with economic and political powers are portrayed and referred to dismissively as ‘trashy women’ because they challenge patriarchal hierarchy whether in context of reproductive health, motherhood or disrupt male-dominated erotic space. Trash again becomes a patriarchal label attached to women because of threats they pose to the institution the male figure represents. In reversal, Kenneth’s model of reading trash approximates the framework in the context of masculinity, especially in the recent phrasing, ‘men are trash’ – an idiom that vibrates an all-out attack against all forms of institutionalized patriarchy that was birthed with gendered alliance movement, #MeToo. And on this front, it opens Kunle’s first Netflix original, Citation, interpretatively and bi-directionally in the critique of trash whether from the prism of the protagonist or the figure of villainy in the film.

In 2019, Nigeria’s moment of #MeToo came with the BBC Africa’s Eye documentary which chronicles the sex-for-grade activities in a Nigerian university. The investigation was carried out by the millennial face of female gender struggle, Kiki Mordi. The Emmy-nominated investigation turned into an epochal moment for feminism as the Nigerian cyber space was awash with narratives of moral failure and oppressive structures not only in Nigerian tertiary institutions, but also in the Christian Pentecostal order and the corporate sector. The account ignited aurally the culture of witnessing in the context of sexual atrocities and shook the patriarchal foundation of most citadels of learning other than University of Lagos, a side which the documentary focuses on. Afolayan’s film also builds into previous viral story of the case of one Professor Akindele who was relieved from the service of Obafemi Awolowo University after amoral demands of multiple rounds of sex from a student, Osagie. Largely, this latter story constitutes the imaginative template for the film. For most female students in Nigeria, sexual harassment is a rite of passage and most are horrendously hounded for amorous affairs by male professors in return for excellent or even grades that do not affect their cumulative performance. Since this obtains within power dynamics, the students are often left helpless sometimes cowered and coerced into these demands. Unfortunately, there is a pervasive culture of silence which makes this endemic. Or if at all there is a crack, such an issue is often swept under the carpet before it gained media attention. Coming with the global momentum, Nigeria’s #MeToo wave became a much awaited moment for accountability in these challenges of lecherous adventure in an institution that should hold the reins of guardianship. Kúnlé Afọláyan took a leaf from this recent event and gave it an artful echo.

The film tells the story of Mọ́remí, a brilliant female graduate student in a Nigerian university who is fascinated by the erudition of an exchange professor, Lucien N’dyare. Lucien, a Harvard graduate himself, is announced glowingly on his first day of class by the dean of postgraduate school. With an interim career at the United Nations, Lucien has an enviable resume that sets him aside as outstanding in the academe with a remarkable number of fellowships. With an angular masculine face and a halo of hairs which signifies his intellectuality, he becomes a center of attraction for most students in the class, and even favorite among the lecturers, and therefore sparks a point of intimacy for Mọ́remí too. Oblivious of his past predatory activities, Mọ́remí would soon find himself in Lucien’s snare despite the warning from his boyfriend, Kóyèjọ. The sequence of actions in the film does not maintain a unidirectional lane, and often the plot is a lapidary detail rolled into layers of flashbacks and backstories which concretize the filmic aesthetic as the past life of Lucien becomes more vivid. Other times, the film foreshadows the danger that lies ahead as seen in the instance of Kóyèjọ the final year medical student teaching Mọ́remí how to defend herself in case of sexual harassment.

Mọ́remí is the protagonist of trash; the one Kenneth Harrow classifies as “trashy woman” in his work. Her character is prefaced with the history and even perhaps pre-empts his representation as a female hero in the film who triumphs against the patriarchal institution. She is the modern transgressive dub of legendary Mọ́remí Àjàọṣorò who is esteemed for her valour in securing Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s freedom from the invasion of the enemy. The antecedent historical figure would devise a means to break into the enemy camp in order to know what methods could work against their attack on her homeland territory. This is also rehistoricized in Afọláyan’s film through rookie actress, Tèmi Ọ̀tẹ́dọlá, who solo-hunts for the past of Lucien in order to make her case before the panel of the university. After their trip from Goree Island, she is seen visiting Senegal again to learn about Lucien’s past from Vincente Cardosa (Ray Boul), a Cape Verdean who comes to Senegal to work at Cheikh Anta Diop University, and by economic circumstance, is exploited by Lucien. It is through this Cardosa’s witnessing of Lucien’s atrocity that completes the findings of the panel and readjusts Mọ́remí from the position of victimhood and shifts her to the site of justice, and subsequently hero. The personhood of Mọ́remí does not give her out as a lousy individual, when one compares her to her friend, Gloria (Ini Edo). She is more modest in her approach on issues. Her meek physique and affable ranges with Lucien are predicted by the latter as affirmation of his lurid sexual desire towards him. However, after the failed rape attempt at his house, Mọ́remí transforms into trash persona – a protagonist who challenges the scocophilic gaze of Lucien and rebuffs his sexual interest in her. Lucien is seen telling her off, “It is not yet over!” But before this rewind of the dinner night at Lucien’s, the movie announces her personality as a trash woman. In the scene where Kóyèjọ, her boyfriend attempts to persuade her not to follow the excursion part of Professor Lucien to Senegal, she confronts him and asserts that he is not the one paying her school fees and therefore could not make a decision for her in that regard. This quickly throws Kóyèjọ off his egoistic balance since he feels he could control her. Similarly, her classification as a trash woman rebounds more in the relationship between Angela, the representative of Àjíkẹ́ Center – an NGO group. She continually reminds her this is her life and it is her case rather than corporate puffery pursuit of the organization. Hence, through this relationship the movie cautions against the overreliance on organizational apparatus in pursuit of justice. Most of the events that eventually propel the downfall of Lucien are individually driven by her.

Taking the leap further, trash masculinity manifests as Lucien is gradually revealed as the villainous figure in the movie. Although this classifier works in reverse with Harrow’s thesis in his theory. It is expandable to the construction of the male figure and the attribution of men with low moral values as trash in context of #MeToo feminist movement. Trash here loses its figural sense and retains its literal meaning often attached to disposability and zero worthiness. Lucien’s portraiture in the film as a pervert elucidates the idiom ‘men are trash’ which some people have alleged to be generic and hasty. On the other hand, some have claimed that the term although seemingly collects men into one camp, it is a pressure idiom for men to act against all forms of oppression and menace that patriarchy represents while also pointing to the exploitative power structures of masculinity. The film begins by showing the peak of Lucien as a well-travelled scholar in the social sciences and someone with an intimidating profile. This is an attractant for students to move closer to him, a camaraderie he sees as a mechanism to win his object of desire, Mọ́remí. In ascribing him with this status of trash masculinity, Afọláyan portrays him as a manipulative individual who seemingly does not know how to drive a manual automobile but owns one back in Senegal. He is involved in trashy activities as a rapist and he is an incorrigible liar who deceives Mọ́remí that he has gotten an interview secured for her at the United Nations. Throughout the scenes of testimony, he is seen inverting the narrative to swing the status of victimhood towards himself. Furthermore, he still assumes his academic profile and patriarchal privilege can be advantaged at the panel and therefore he is seen bellowing at the students’ representative, Uzoamaka (Bùkúnmi Olúwaṣínà) about his towering achievement. In response to this confrontation, the chairman of the panel, Professor Awóṣìkà who is also a Rhodes scholar, serves him a rebuttal that quickly deflates his male ego and further foregrounds him in a trashy position. He is further transposed into this figure as he is relieved from the University’s service; Mọ́remí is vindicated and he is reduced to what Harrow surmises as “fallen man”.

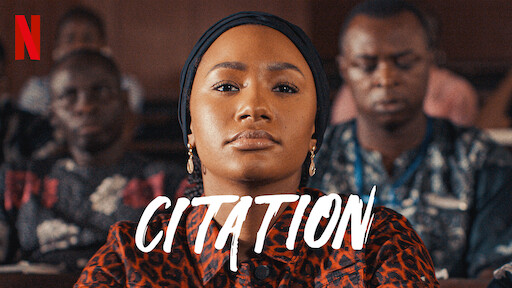

Kúnlé Afọláyan has become a household name in Nigeria’s film industry with movies in his oeuvre that show he is an auteur to reckon with. With this, he enjoys generous scholarly patronage. While Citation lists him further for his excellent cinematography, set construction courtesy of Pat Nebo, and ambitious casting which compiles A-list actors such as Jọkẹ́ Silva, Rọ́pò Ewénlá, Yọ̀mí Fash-Lanso, Jimmy Jean-Louis, the film also provides a strong pan-Africanist statement linguistically and spatially. Although Kúnlé Afọláyan has been haunted by Nkrumah’s ghost since the release of his thriller, CEO, which stars Angelique Kidjo. Another stronghold of the film is mood music with Youssef Ndour, Babátúndé Ọlátúnjí and others holding the stakes. The dialogue is not too hollow but dotted with memorable lines that leave some scenes in an audience’s mind. This latest release which has gone ahead to be the most sixth viewed globally ranks outside the bracket of his earlier films such as October 1 and The Figurine, partly fails because of characterization of the protagonist evident in her Yorùbá and French accents. The shortcoming also becomes more discernible in the elongated scene such as Ṣeun Kútì’s performance. For Kóyèjọ, a part six medical student working on a cadaver shows the film lacks some rigor. Generally, there is less suspense work in the film, and often the plot is predictable. But understandably, this positions the film for a commercial advantage since it is addressing an issue that has currency.

In sum, Citation provides profound artistic comment on decadence in an African ivory tower, an institution which should serve as a moral compass for the society. The film is least cited Afọláyan’s film yet. But then, it positions him as a director of feminist affiliate and further shows the generational shifts in gender question in Nigerian society where young women have become most vocal against patriarchal hegemony in various Nigerian institutions. This is most visibly illustrated in the recent #EndSARS protest where a spring of young women took the vanguard and confronted the tyranny of silence, wanton police brutality and leadership failure.

Salawu Olajide is the managing editor of Olongo Africa, an arm of The Brick House.