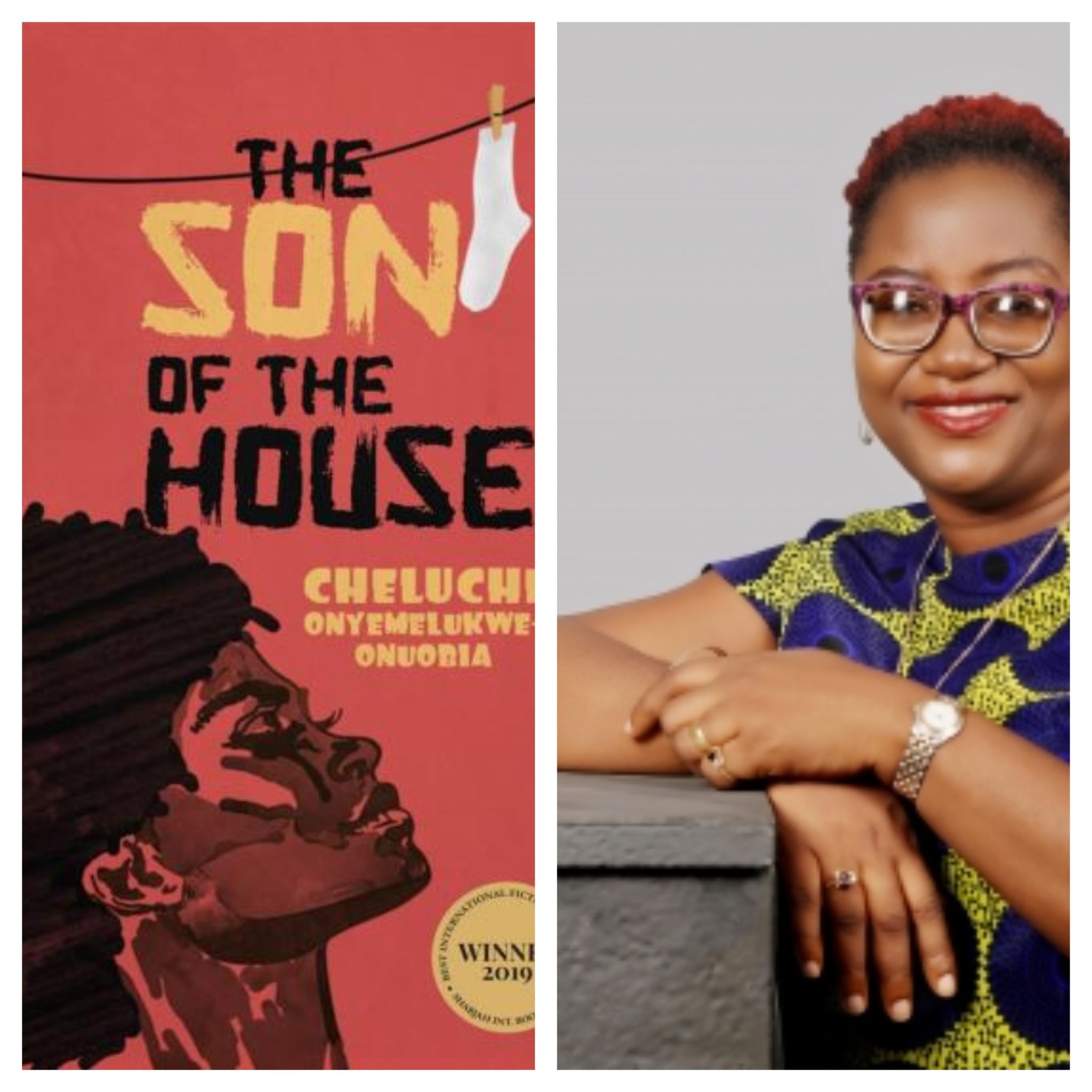

Cheluchi Onyemelukwe’s debut novel, The Son of the House, won the award for Best Fiction Writer at the 2019 Sharjah International Book Fair.

Uche: Congrats on The Son of the House—a heartrending novel dealing with rape, teenage pregnancy, treachery, and female oppression. What was it like writing it, and how did it start?

Cheluchi: Thank you. In retrospect, it was a rewarding, sometimes hard, experience writing it. I had a story to tell but it took me a while to figure out how best to tell it. I say ‘in retrospect,’ because one can forget that the experience of actually writing the book, especially as it picked up and one began to live with the characters, was not as torturous as the submission and rejection cycle sometimes makes it seem. I heard a story from my mother that moved and troubled me, feelings which I tried to resolve by writing this novel, which then took on wings and flew in other directions.

Uche: Why did you choose to use different narrators, and what made you decide on that narrative structure?

Cheluchi: The book actually began with ‘the son of the house.’ But as I wrote it, I found that the stories of the two women resonated more, spoke to each other and to me, in a more insistent voice. Technically speaking, I wasn’t sure if it would work for other people, and especially in the end, I wondered if it really worked, but the reviews suggest that it did for others, the way it did for me. Working with the two narrators allowed me to show different aspects to the experience of being female in a certain time and place, and to draw the similarities despite outward appearances of differences in the backgrounds and lives of the two women.

Uche: What would you do differently if you were to rewrite the book?

Cheluchi: This is a difficult one. I can’t think what I would do differently, seeing as the book is a product of revisions and going with the characters in the directions that their voices led. However, I would say that many have taken issue with the ending. Some have called it a cliff-hanger, and some have said ‘unsatisfying.’ Others have asked if I would write a sequel. I think about that on occasion, but not with vigour.

Uche: The Son of the House is mainly set in the 1970s and 1980s, though its critique of gender relations reflects today’s realities. Why was it important for you to set the story during those periods?

Cheluchi: I am a child of the 80s. I grew up in that time. It was, I think, growing up in that time, and being around my mother, our relatives, her friends, the people that we lived with at home, and seeing life through their eyes and hearing the things they spoke about, the things that bothered them, the stories they had of others, and having questions that went unanswered. People have commented on the book’s honesty and lack of contrivance, and I really think it mirrors that time. While that time reflects times past, these experiences, the struggles of women, the issues of class divides, the understanding of the place of women and men are still here with us. So, in a sense, while it is somewhat historical, these things live with us, even now to a certain degree.

Uche: It also criticizes aspects of Igbo culture and traditional masculinity. What has changed for Nigerian women, and what opportunities do you think they now have?

Cheluchi: I think a lot has changed and will continue to change. There is a more urban feel to life (which is not all good or all bad). There is social media. Women and girls and also men are exposed to the fact that life can be different (again, this is not a value judgement, not about ‘good’ or ‘bad’). Women are in the news doing things on the world stage, having fewer children (sometimes none). The move towards urbanity, the continuing migration within and without, often means that culture is maybe not necessarily changing, maybe getting watered down. While some couples still prize having a male child, for example, it is becoming less difficult to point out people who live in Lagos or London and who have 2 or 3 girls and seem quite content. Is the culture completely changed? The short answer is ‘no.’ Is marriage still prized? Without question, yes. To a large extent, though. Do women see how things could be different, more and more the answer is yes.

Uche: As a follow-up question, I recall a scene in which Julie/Mrs Obiechina remarks, ‘It was important for a woman to have a life.’ Yet, such women as Mama Nkemdilim, Mama Nathan, Mama Odinkemma, and Madam tend to perpetuate patriarchal scripts and practices. How do we get women to recognize how they are implicated in their subjugation in society?

Cheluchi: Another difficult question. It is not the easiest thing to recognise when you have been born in, steeped in, a certain milieu, that all of the culture, good and bad, permeates deeply. There is a role for every aspect of society in the unbundling and deconstructing gender norms, in the advocacy for social change. There is a role for social media, our growing awareness to use that as a tool for championing change. There is also a role for the arts, music, writing (and I mean that very broadly, in books, but also in internet-driven media) to interrogate things and change the dominant narrative, the aspects of the culture that no longer serve us, that hold us back, while retaining what is good and continues to serve everyone.

Uche: Society rarely sees a man as “man enough” if he fails to produce a son, and there is much emphasis on the male heir in the novel. That scene where Eugene declares, ‘I know it’s a boy,’ is telling. Could you say a bit about this?

Cheluchi: Well, this is something that I have seen up close. It may not be general, but it is certainly strong in Igbo culture. To be fair, it has its uses – for lineage security, especially, and from a broader perspective, one could argue that it is central to the understanding of the family, community, history – think of the umunna system, for example. One could even go so far as to argue that by extension the entire culture is founded on the idea of a son carrying things forward. But I wonder where that leaves women. And, like you noted, it is also burdensome on men, who seek solutions in ways that are often inimical to the interests of women. Why should we define masculinity or manliness by something not always within one’s control? It may be weakening, but we have quite a long way to go with this notion as people working in Nigeria’s fertility industry will testify.

Uche: The impact of the Biafra-Nigeria war is implied in the story, but not depicted. Did you find it difficult writing this into the story, considering that we loathe talking about that part of our national history? As a writer, what do you think about literature and politics?

Cheluchi: I like to tell a story, first and foremost, as a story. And so, history has to fit in there for it to make an appearance. My goal was to share these women’s story in a particular milieu and the war did make its way in, but only peripherally. It wasn’t really a matter of difficulty. But I suppose you are right about the difficulties our political leaders have about talking history, and unfortunately, allowing us the liberty and room to have these important discussions even as history rears its head in our ongoing troubles. I think literature and politics are important parts of our consciousness and humanity. Literature is inherently political, however, you look at it. The freedom to write what one chooses to write and have it accepted or not accepted, only on its merits, is political. My story, as domestic as it may sound to others, is quite political. Novels dealing with the war, even through the eyes of a family’s survival, are political – they are saying – ‘see us, we are here.’ Sometimes writing/storytelling is more viscerally political, of course, dealing with the politics of the day.

Quite a bit has been written about the seriousness of ‘African’ literature and how our forefathers and foremothers often wrote of serious matters and took the responsibility of being the conscience of the times seriously, and how we want to be carefree and write horror stories and romance and all these other lighthearted things. And, more and more, some of us have moved in the direction of the ‘less than serious.’ Nothing wrong with that of course. Indeed, it is necessary, especially when we look at things from the perspective of the whole human. We are surely more than our more known traumas –colonialism, military rule, etc. But I see again today, in the context of Nigeria, in particular, and inequality in different spheres across the world, for the role (and need) of the writer as the conscience of society. In Nigeria, for instance, we see the sceptre of militarism, fundamental rights infringement, and the challenges of insecurity which have visited everywhere including our schools. The recent Twitter ban by the current government is a case in point. How can we look away from that, and what that represents (a time that we thought was in the past, a boot on our collective necks, a forcible shutting up of our voices) in our oral storytelling, essays, poetry, drama, creative non-fiction, short stories, novels, Facebook updates, tweets, Instagram updates, or any other avenues of doing literature?

Uche: Which authors have influenced you as a writer?

Cheluchi: This is often a difficult question for me to answer. While I continue to read and reflect on ongoing influences, I think that most of the books I read as a child and young person influenced me most. I have a sentimental place for Chinua Achebe, Kola Onadipe (whom nobody speaks about), Cyprian Ekwensi, Flora Nwapa, and many others that I read growing up, who made me think of being a writer, of telling stories, and being accessible while saying hopefully meaningful things.

Uche: Finally, how soon are we expecting your next novel?

Cheluchi: I wish I could tell you. My publishers would like to know too, I am sure. But I am working on it, in the midst of doing life. I hope it will be sooner rather than later.

Uche Peter Umezurike holds a PhD in English and Film Studies from the University of Alberta. An alumnus of the International Writing Program, Iowa, USA, he is a co-editor of Wreaths for Wayfarers, an anthology of poems. His children’s book Wish Maker is forthcoming from Masobe Books, Nigeria in fall 2021.