Romeo Oriogun has always regarded his life as some form of “protest”, and in many ways, he’s not far from the truth.

As an artist, he has had to go against the grain, hone his craft and churn out the kind of poetry that was (derisively) described by (older) literary purists as “trauma porn”, all the while having heated conversations with his muses in rhyme and verse. As a man, he has experienced loss in several dimensions, been spurned by death on several occasions even when he knocked earnestly at its door, and has been subjected to physical assault on account of his personal choices.

Oriogun breathes art and has proved his mettle as one of the finest ambassadors for a generation of young, irreverent, convention-defying African poets. From harsh concrete floors in Ikare to the lecture halls of Iowa State University, his tenacity has paid off, but a flourishing career has not come without a cost: the need to flee a homophobic country that is at the same time insensitive to mental health concerns has resulted in exile for the 34-year-old.

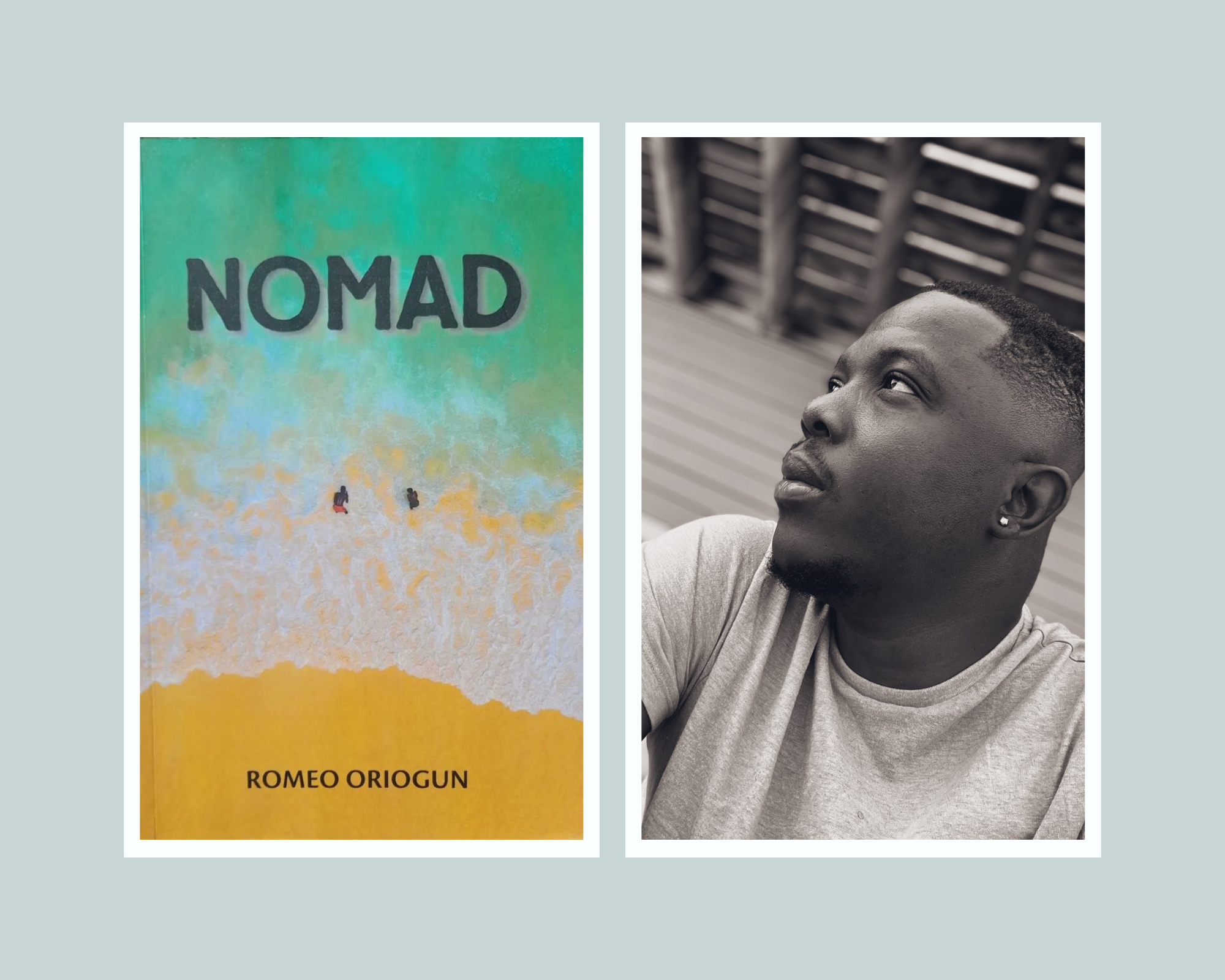

It is from this exile that Oriogun, winner of the 2017 Brunel Poetry Prize and finalist for the 2021 Lambda Award, summons the elements to hear him out in Nomad, his second full-length collection of poetry. Published by Griots Lounge, this book houses 67 poems that seek to chronicle the travails of a bard’s restless spirit.

“Beginning”, the aptly-named opener for this collection, paints a vivid picture of what it means to be uprooted from a land you’ve called home for more than two-thirds of your life. Oriogun’s disillusionment is palpable as he writes “the weight of a country will always be too heavy to leave in a strange park.” Migration goes way beyond the slinging of luggage; stories and memories are conveyed across borders, too.

In “Mist” memories of home and a distant past float across all corners of a worried mind, and the tone of “Everyone I Love is Alive Tonight” is eerie – in the manner of Florence and The Machine’s “Only If For A Night” as Oriogun processes the absence of a departed friend, mother and sibling, stretching out to them as he sits by the seaside, yearning for an audience.

“Everything is silent, even the sea/all sentences are victims of time/I do not know what the world wants but tonight/I am dancing to the incomplete nature of existence…”

“Cotonou”, one of the collection’s longer poems, lyrically illustrates the perils that accompany attempts to migrate across unkind shores. As nicotine saunters into the lungs and smoke is sent up the air like a sin offering, Oriogun conducts a five-part interrogation of all the actors in this crude dance that plays out along the Sahara: women are subjected to inhuman treatment in dingy brothels, music ushers in the voices of the wandering dead, fancy parks provide ugly reminders of slave trade, and strong winds sing in commemoration of bodies thrown into the sea in centuries past.

“The voice of exile is a murmur crossing rivers/and sea, crossing empty roads until it washes/over a man, a baptism of loss.”

In terms of narrative direction, travel segues to history as “An Old Song of Despair” sheds light on the women of Ewu in Edo State whose thriving cotton industry was destroyed by the intrusion of colonialists. Lurid details of the 1897 British invasion of Benin City are captured in “Waiting for Rain”, and colonial subjugation dominates the discourse in the poem “At Lagos Polo Club.”

Oriogun puts his spirit to task whenever he travels, as he invokes the souls of murdered natives and heroes who were bludgeoned for mineral resources in “Postcards from Abandoned Places.” In these grim pages, he holds nothing back in wailing about darker decades past: how many history books care to talk about the scores of chieftains who were executed by the colonial administration in the old Calabar region, as poignantly illustrated in “Killing The Condemned”?

Nigeria is sometimes described as a glossy pile of debris, and it is with elegant (albeit rueful) poetry that Oriogun guides us through the wreckage: a young boy is slain during a riot in Benin City, child soldiers have their eyes plucked out during the Civil War, a war veteran grapples with sweaty nightmares, and a journalist seeks asylum for fear of his life. The messiness of colonial conquest seeps through the entire continent: from Nouakchott to Windhoek, isn’t Africa’s history marked by exploitation, lies and blood?

In his essay for The Africa Report titled “Send Me About 100 Naira to Celebrate Buhari’s Second Term”, Nigerian poet and music critic Dami Ajayi likens migration to “learning to walk again” and describes living abroad as “constant tom-peeping at your natal country because your exile is contingent on its failure.” In Nomad, Oriogun goes a few steps further and beams the spotlight on the torture that comes with mulling over what home was and what home could be. However, it’s in ruminating on the afterlife that he pulls no punches: no one is particularly indifferent about mortality, but in these 116 pages, Oriogun takes the Coldplay lyric “those who are dead are not dead/they’re still living in my head” (off the track “42”) to a different level.

Burnt Men may feel like a lifetime ago now, but Oriogun shows no signs of intellectual fatigue, even when the conversation is different. The poetry is still incisive, still probing, still abundant in cadence. At its core, Nomad is travel poetry, but it also holds the feels of a memoir being crafted by a voice that is as intentional as it is authentic. Even in his despair tone, even as he struggles with the burden that comes with displacement, the beauty of Oriogun’s poetry shines through.

Jerry Chiemeke is a writer, editor, film critic and journalist. His works have appeared in The Africa Report, The Republic, The Johannesburg Review of Books, Netng and The Lagos Review, among others. He lives in Lagos, Nigeria, from where he writes on Nollywood, African literature and Nigerian music. Jerry is the winner of the 2017 Ken Saro Wiwa Prize for Reviews, and he was shortlisted for the Diana Woods Memorial Award for Creative Nonfiction. In 2021, he covered the Blackstar International Film Festival in Philadelphia as a film journalist. He is an alumnus of the Talents Durban Initiative.