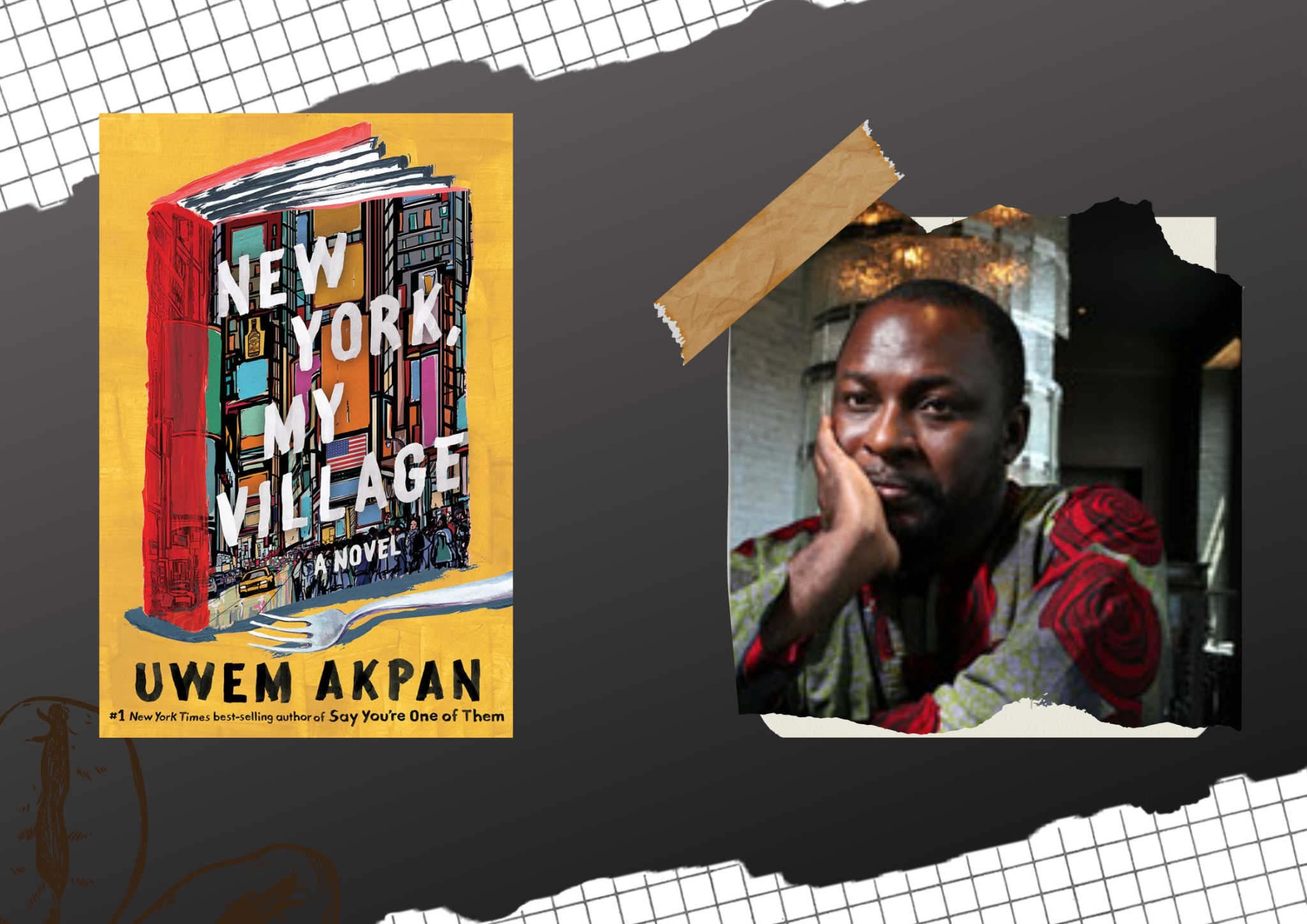

Uwem Akpan is not an unfamiliar name in the annals of African literature. His debut collection of short stories – Say You’re One of Them – made the New York Times bestseller list, won the 2009 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, the 2009 Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best First Book, Africa Region, 2009 Beyond Margins Award and was a Finalist for the Los Angeles Times Seidenbaum Awards for First Fiction. And was selected by Oprah Winfrey for the biggest book club in the world to read – Ophrah’s Book Club. Currently, his foray into the long fiction genre in New York, My Village (hereafter referenced as NYMV) has demonstrated Uwem Akpan is a versatile storyteller.

In this debut novel, the Nigerian-born, US-based author has once again distinguished himself as a significant voice in the African literary circle with his attunement to pivotal concerns that deserve urgent contemplation and conversations. Uwem Akpan, who teaches in the University of Florida’s MFA Program takes a bold approach as he grapples societal issues with immediacy, empathy and keen insight. In line with its title, Akpan skillfully teases out the nuanced similarities and divergences between New York and Ikot Ituno-Ekanem in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria – the two settings in which the story revolves. In that sense, the verdant valley in Ikot Ituno-Ekanem takes on a different meaning when brilliantly juxtaposed with New York City’s Times Square. Through characters that are diverse and complex, Akpan evinces the intricate ways by which multi-ethnic and multi-racial grievances obey no geographic boundaries but occur in damaging ways all around us.

The events in NYMV unfold through the eyes of the protagonist and narrator, Ekong, who travels to New York City as an understudy at Andrew & Thompson publishing house. Thrown into the grim reality of navigating micro-aggressions and the politics of whose stories are told and which are discarded, Ekong soon learns that the captivating veneer and glamour of New York with all the promises it holds can not hide the complex yet startling realities of racial landmines, even for a visiting minority. Although the author offers no quick remedy to these issues, the novel condemns complicity, willful ignorance, and a lack of introspection through the unfolding dramas between the diverse and interesting characters in the novel. The author’s use of the first-person narrative centers the narration around the protagonist’s perspective which is sometimes coloured by lived experiences, gathered information, interactions and bias. The conversations are illuminating, heartbreakingly raw, and distressing. The author must be lauded for the painstaking research that went into the creation of this work. But the downside of this is that certain parts of the novel read like a documentary and one comes away feeling overloaded with information.

The overarching theme of NYMV is the undeniable yet often overlooked effect of the Nigerian civil war on minority ethnic groups in Nigeria. The author sets out on a grand scale to uncover and debunk several myths surrounding the war, and he accomplishes this feat albeit in a heavy-handed manner. For example, Akpan underscores the distrust and divide the war brought to bear on intra-communal relationships in the Annang community as well as the fracturing and breakdown of inter-relational connections between the warring groups and other minority ethnic groups. Writing about the war of 1967 – 1970 means delving into the past through the lived experiences of different characters and various stories from community members. This back and forth creates the necessary tension and suspense needed to move the plot forward and validates the varied experiences of the characters. Through the haunting subject of war trauma, the author builds thematic connections between the past and the present, Ikot Ituno-Ekanem and New York, ethnic and racial dichotomy, allyship and adversary while challenging the dangers of a single story. Akpan offers a haunting tale that not only recounts the horrors of the war on minorities but raises questions on man’s inhumanity to his fellow man. In doing so, the author asks the reader to create and hold space for uneasy conversations.

New York, My Village is undoubtedly an important literary work on the Nigerian civil war and racial issues in America for immigrants of colour. Although Akpan notes that “New Yorkers spoke in code about racism” (276), one feels grateful the author is not bound by that crippling custom in this work. Therefore, what shines through is the author’s mindful and thorough handling of delicate issues and trauma. For a novel that opens with the stupefying question about the existence of the Annang ethnic group, the use of Annang words, phrases, dialogue, songs and meals throughout the novel firmly grounds it as a cultural masterpiece, and this is by far its greatest achievement. My most memorable passages are parts where the conversation organically drifts into Annang language because they are wholesome and effortless. Scholars of war literature and lovers of history will enjoy this work

Kufre Usanga is a PhD student in the Department of English and Film Studies at the University of Alberta, where she researches petroculture and Indigenous literatures. Usanga holds the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Doctoral Award.