“Is your VPN on?” asks Anthony Azekwoh. We’re on the now-familiar Zoom app, attempting to get into a meeting together. Days before our call, the Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari declared an unconstitutional ban on Twitter, forcing millions of Nigeria-based users to access the social platform through a VPN interface, which is able to bypass territorial constraints. This service however slows its network and is totally incompatible within other apps; hence, Anthony’s question.

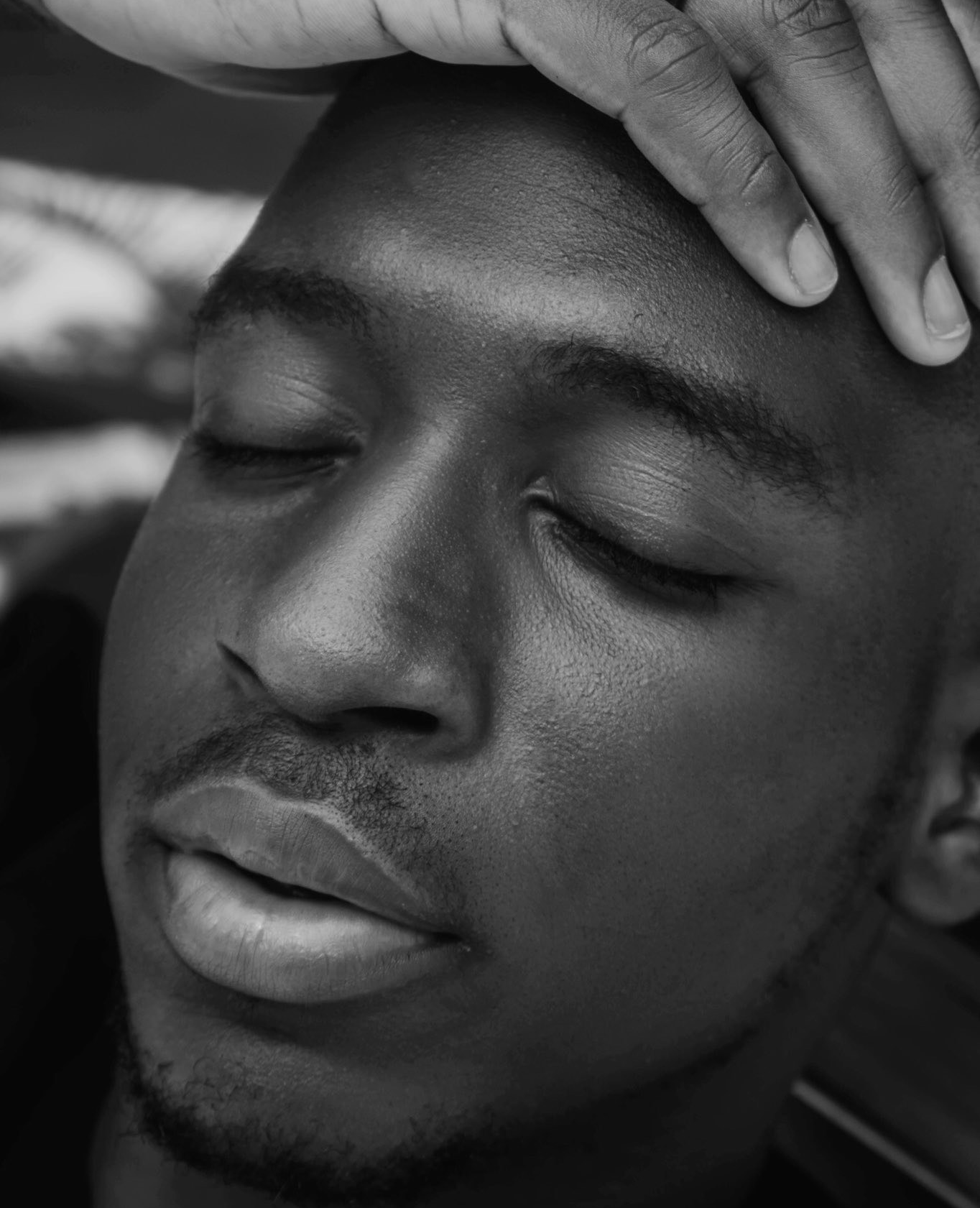

Few minutes later, his voice came on indistinctly in the background, signaling a successful connection and the start of our conversation. The camera reveals Anthony in a pink shirt, in calm contrast with the white background of his room and a half view of his polished drawers. There’s no splattered paint or littered crumpled paper. This, I reason, is not the image many think of when they hear the word “artist.”

21-year-old Azekwoh, whose foray into digital painting began in 2016, paints with Adobe Photoshop. Then a budding writer, his laptop got spoilt and before it was repaired, Anthony started drawing with ink pens on A4 paper. The next year, he encountered the work of Sam Spratt, an American designer whose digital paintings masterfully retain the brushstrokes of a traditional painting. Anthony had seen Spratt’s cover for rapper Logic’s Under Pressure album. “I remembered thinking, ‘this is what I want to do’,” he said. He watched YouTube videos, read books and got feedback from a small network of friends. Though inspired by Nigerian designers like Duks Arts and Duroarts, the youngster’s reach was limited, and remained mostly self-taught.

Four years on, Azekwoh is one of the most visible digital artists in the continent. His work has sold in countries he hasn’t thought of visiting. Homewards, he’s a signifier of the wealth of visual art coming out of Nigeria. Anthony channels a variety of influences: neoclassical painters like Jacque-Louis David, who painted one of his favorite works, The Death of Marat; the American illustrator Norman Rockwell; Anthony has also done a self-portrait inspired by the Japanese art, Kingitsu, wherein broken pottery is mended with powdered gold or silver.

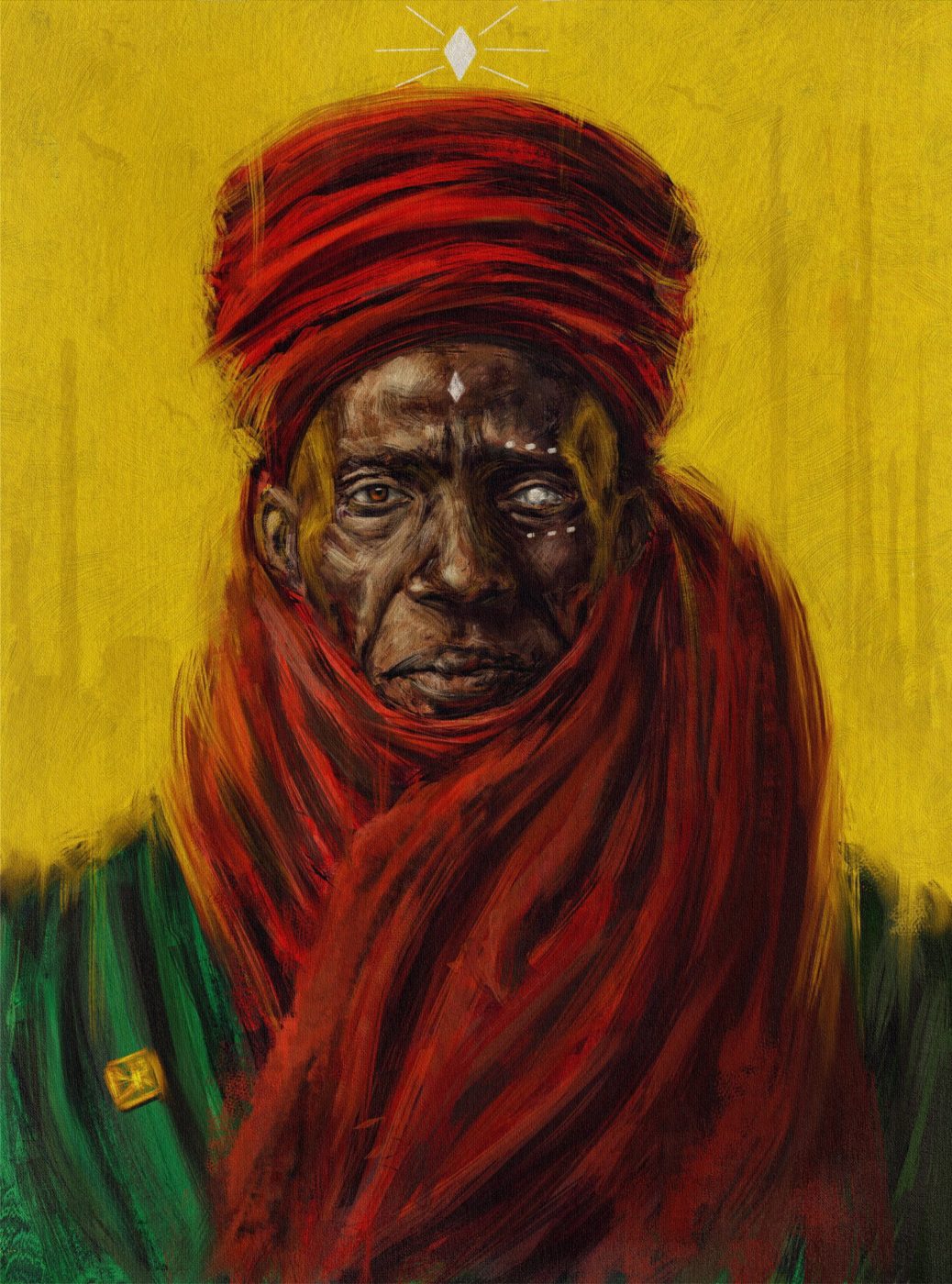

Azekwoh’s paintings are memorable, inviting the viewer to build their back stories. He’s painted historical figures like Mansa Musa, the richest black man in history; contemporary celebrities like departed creator of the Marvel universe Stan Lee; and, as well Jesus Christ, though Anthony’s focus traverses the typical divine aura, opting for the despair of a mortal man.

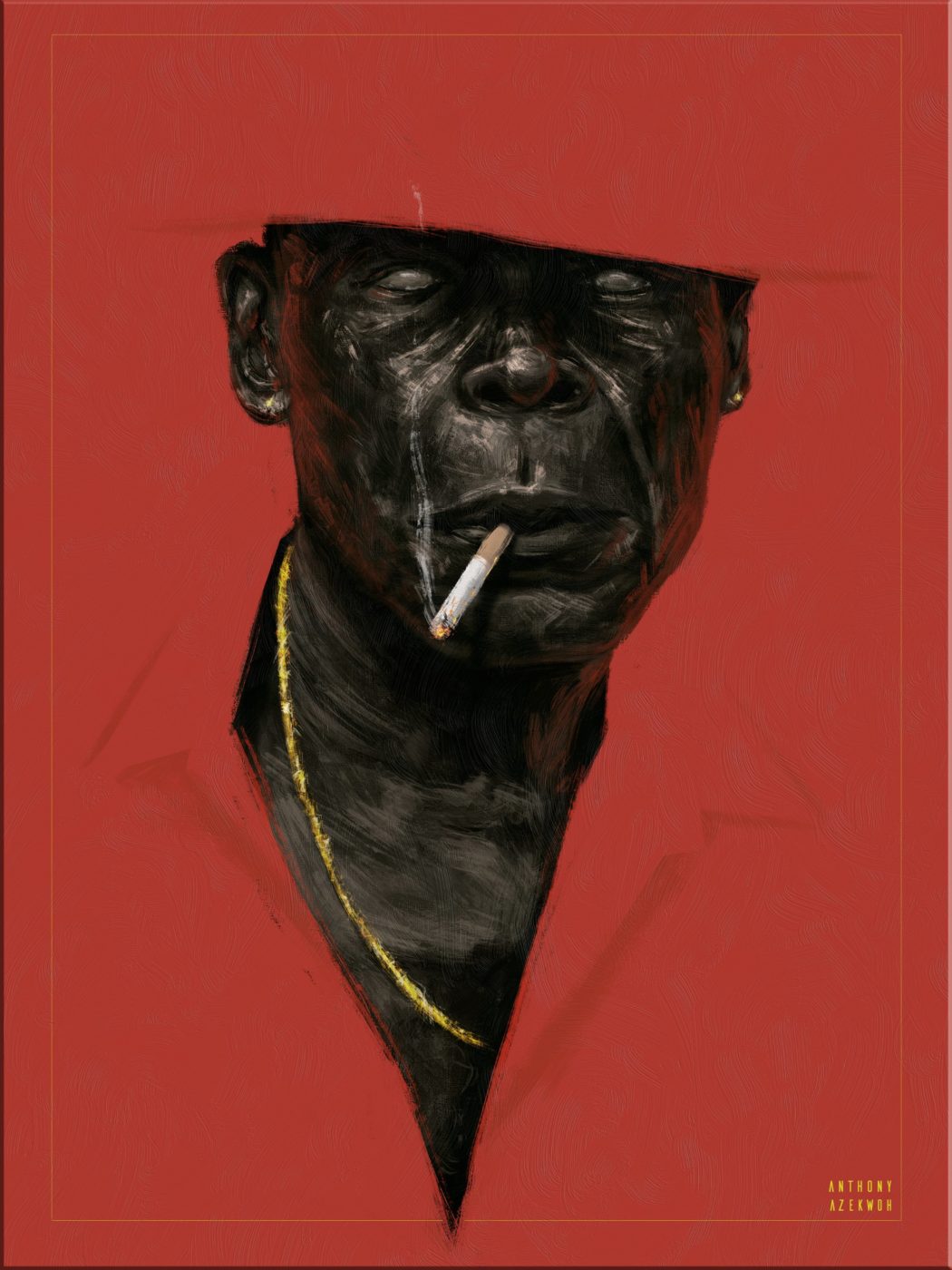

The Deathless Series, composed of mythic figures, is Anthony at his creative best. Characters like The Traveler and Mama Gold possess a stunning depth in their appearances and especially their bleached eyes that achieve a powerful effect with the colors abound elsewhere. Last year, Azekwoh created the series’ first “The Red Man” –it’s now his most popular painting, with over 230k likes on Twitter. “I wanted to quickly paint something in black and white ‘cos I had things to do,” he says about the night it was made. He thought of using a red background and it looked well. “It was maybe 2am and I didn’t have time to [color the eyes] so I just said let me leave it like that, it looks nice. A person’s eyes, you can see so much in them –it’s a focal point.” The next morning, Anthony looked at the painting and for the first time felt what many have described as “chilling.”

The mystic contours of reality are captured in the unusual faces of characters from the series, their stoic-yet-passioned gaze, all of them like the inhabitants of an otherworldly house. I suggest that Anthony’s first love (which is supernatural literature) influences his characters (a publisher, he later affirms, has said the same) and ask if he’s written about them. “I don’t really write about my paintings,” Azekwoh says, but admits that a story, ‘The Garden of Old Lagos’ inspired ‘Adam and Eve,’ a latter painting. “I feel like everything exists in its own world and I don’t need to mix too much.”

Anthony Azekwoh grew up in Surulere, a middle-class Lagos area renowned in contemporary Nigerian music history; when we discuss this neighborhood, Anthony recalls the Wizkid craze of the 2010s, when most teenagers mirrored their fashion and personality off the Made in Lagos star. Literature was the preferred art form of Anthony. “I just needed to read,” he says. “I was one of those children who couldn’t stay in one place and I had this good grasp of the English language. It started with storybooks like everyone else. My mum saw that I [loved books] so she’d sit me down and we’d read newspapers. She’d select the pages to make sure there was nothing too much there.”

At 8, Anthony read Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah The Windseeker and the novel “changed my whole perspective on Literature. Before then, I’d been reading all these Enid Blyton, Cinderella books and it never occurred to me that not only could a black person be in a book, the black person could even be Igbo. It blew my mind.”

Anthony dug deeper into books, spending “ninety percent” of his pocket money on new titles. In secondary school a now-renowned author became his mentor. “Kola Tubosun was our teacher at Whitesands School. Before that I had never seen a writer in person. Writers were always these mystical people, like unicorns, writing in a cave somewhere,” he says with a soft chuckle. “He was the first writer I’d seen in my life and he wasn’t dying of hunger.”

Mr. Tuboson – described as “engaging and inspiring” — bonded with Anthony, by then the winner of writing competitions in school. The teacher once asked his students to create a blog and from there Anthony acquainted himself with WordPress and online publishing. The Fall of the Gods, his first book, was written between 2016 and 2019, and an early version was run as a series on literary platform Brittle Paper. “The book sucked,” Anthony says bluntly. “I didn’t have the discipline to really work on some things. Time passed, I wrote more books and I’m still learning.”

In Fall of the Gods, Azekwoh draws from Nigerian mythology, using inter-ethnic deities like Amadioha, Sango and Ogun to input a unique spin on a popular tale: how the old gods lost their power over humanity. The book’s opening scene is enriched with praise for the heavens, where the gods are having a party. Sitting alone, Ṣàngó is pensive. He looks at Ògún, “a large being, even by god standards,” whose other features could as well be described a typical Azekwoh character: “…a scarred face and a hard set jaw, and he always looked like he was contemplating the best way to kill you.”

His writing comes across as measured. There’s little floss and every introduced element serves narrative purpose. Though TFOTG suffers an underexplored plot, it relays a basic grasp of technique: its dialogue intrigues and flashbacks are handled neatly. Like Azekwoh’s favorite writers – a long list including Neil Gaiman and Rick Riordan — he makes the complex simple, channeling ancient myths into stories, demystifying the nature of humanity’s connection with the supernatural and making crucial observations on histories. In 2019, he won a $1000 Loose Convo grant for five interlinked short stories on the given themes of History, Heritage, Pride, Body Enhancement and Prejudice.

For generations, black writers from Toni Morrison to Nneka Lesley Arimah have utilized speculative elements in analyzing sociopolitical tensions of the past, present and even future, through dystopian narratives. Azekwoh’s tales, similarly, are imbibed with historical context, the Nigeria-Biafra War especially prominent as a plot device in some. Though Nigerian mythology, rich as it is, hasn’t been well appropriated into popular culture, Anthony recognizes a gradual shift, of Nollywood filmmakers subverting from the comedy and get-rich tropes. He also confirms forthcoming work on myth-inspired projects.

I ask if he’s heard the dismissive notion that genre fiction isn’t serious Literature. “It’s funny when people make all these rules for art,” replies Anthony who’s now written five books. “When people try to involve their egos [and dictate what is right or wrong] it just removes the whole point. To me, art is about expression. I couldn’t tell you the difference between genre fiction and any other fiction. I go wherever I’m interested in.”

Azekwoh’s multidisciplinary approach to art has, for some years now, proven to be the zeitgeist of the Nigerian creative space. With little help from the government, these people are in their teens, twenties and thirties, photographers, designers, musicians, videographers, filmmakers, artists, producers, journalists –learning online and networking on social media, pushing the bar in their intersecting fields. Anthony has previously name-checked Chigozie Obi, Omotola Oyefodunrin and Mumu Illustrator as some of his favorite Nigerian graphic designers; today, we’ve discussed the merit of creatives like Niyi Okeowo and Blaqbonez, a rapper whose album cover was designed by Anthony. (Many of the mentioned designers have also designed covers for musicians, a marker for the expanding relevance of art direction in the entertainment scene.)

When the Nigerian presidency announced the ban on Twitter, Anthony’s initial reaction had been a tweet: “I cannot explain Nigeria to anyone not familiar with the headache. How do you upload a press release, on Twitter, banning Twitter?” It’s becoming increasingly aware to young Nigerians that the brand of respect expected of youths has fuelled the authoritarian excesses of the present administration. Across varying levels of the national system, in local government offices and universities, this disregard for young expression (fashion, dreadlocks, tattoos, Art) has been well documented. Anthony once penned an essay condemning the practices of Covenant University where he’s currently a student.

“With Nigeria you don’t even triumph, you manage,” he says with a sigh. “Creative work already is stressful, then you now have to fight your government – it takes a toll on everyone.”

In such a social and economic climate community building becomes essential in nurturing creatives into self-sufficiency. Azekwoh recently announced Nengi Uranta as the inaugural recipient of the Anthony Azekwoh Fund (AAF), a grant he set up for emerging artists. “I’ve done a lot in the past year and I was proud of the work. I wanted to do something to give back,” he explains. There are plans to expand the grant and start receiving donations but the AAF first has to be registered as an NGO. Along with other creatives, Azekwoh also hosts regular meetings on Twitter Spaces where many career details from development tools to standard prices for certain jobs are shared and discussed. As opposed to the dearth of similar communities in the past, Anthony praises the “openness of top artists” in recent years.

In character with his forward-thinking nature, Anthony has joined a growing number of Nigerian artists minting their works as NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens). The crypto medium has been heralded as a groundbreaking tool which eliminates the need for middlemen: the product follows a direct chain from buyer to creator irrespective of location, and payment can be made in a variety of ways, etherium included. “It’s a huge problem solver,” Anthony says animatedly. “Imagine you’re American trying to pay me for my work. You’d normally pay me in dollars and I’d have to convert to naira. The used platform would collect a ridiculous percentage as interest. But just imagine you need to send a thousand dollars and you send as crypto, and I receive that exact sum. If it were more widely used and understood, and maybe even regulated, it’d be a perfect alternative to solving the international problem of communicating.”

Our conversation ends with me asking Anthony what he’s been dabbling in recently. “I’m expanding the medium,” he affirms. “I’m moving away from painting and just working on something else. I’m reading a lot more, learning, and looking at more work. I’m especially trying to improve my drawing skills. I’ve done good work in the past but all that is a starting point. I’m still young in the craft and I know there’s so much I have to do.”

Emmanuel Esomnofu is a Nigerian writer. His work investigates youth culture and histories. He’s also a media professional, with interest in storytelling and branding. He’s a staff writer at Open Country Magazine.