You don't send out invites to these things. So obviously no RSVP's in return. It's all guess work. There's a metaphor somewhere in there. I'll work it out in a minute. – Aduke Gomez

There is, among the Bambuti of the Ituri forest in the Congo, the impossible music of the bamboo flute. This flute can only play one musical note and yet these ingenious people have made polyphonic music possible with it. Reading On Attending My Own Wake and Other Episodes is, in some ways, an experience akin to listening to the flatline and yet hearing the distant drum that speaks of the heart that never dies in humanity, the consciousness that is never completely buried. The supposedly simple Bayaka developed polyphony through dialogue with their flutes. The intent gaze of the mind makes these things possible on the page.

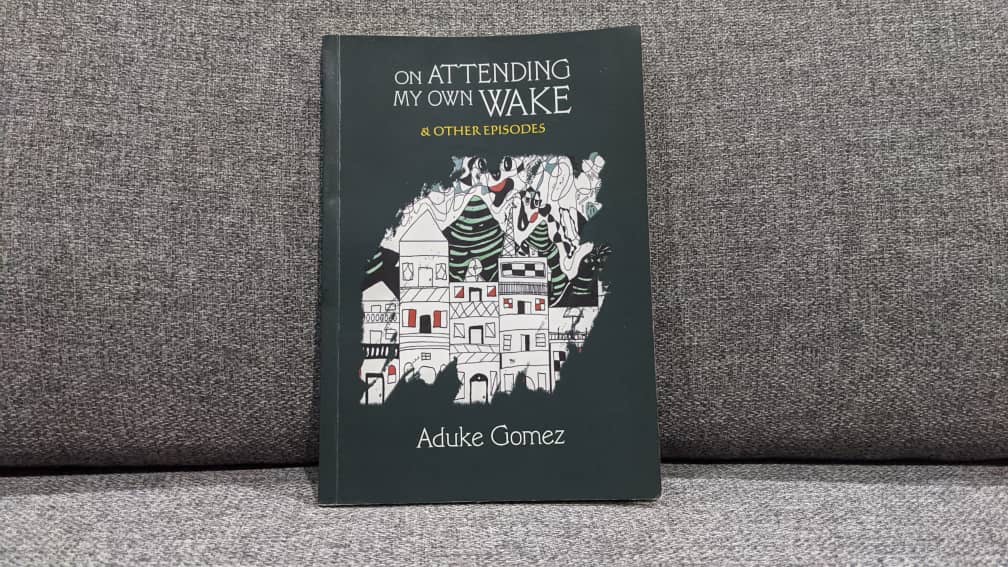

It is a thing of supreme difficulty to write about hard things with clarity, truth and music. On Attending My Own Wake came with this uniqueness In a society that has succeeded in banishing taboo subjects to the realm of whispers, Aduke’s unsettling script marks a point of departure and of supersession. There is dark humour and candour here, but, uncannily, there is hope too, and a throbbing pulse.

In her brooding on the subject of death by suicide, Aduke Gomez both broached and bucked speech with a searching execution of monologic discourse which, perhaps, is the most honest door into the suicidal dark. Helen Vendler, the poetry scholar and critic remarks in The Given and the Made that the purpose of lyric, as a genre, is to represent the inner life in such a manner that it is assumable by others. She further observed that the inner life, by definition, is one not engaged directly in social life. The really clever thing which the poet began to do in On Attending My Own Wake was to juxtapose the inner life of the persona against the backdrop of a wake, which is, in most parts of the world, a social construct.

There is both an autocritcal and an allocritical dimension to the discursive range in On Attending My Own Wake and Other Episodes. The persona begins with the self:

I don't know why I came really. It's just as I thought it would be. Boring. But with an underlying dread anxiety. Like sitting in a waiting room In a dream.

In due course, the persona adopts the allocritical mode and practically eviscerates certain elements participating in the wake obviously out of a sense of duty that would have been put to better use in the life of the now accomplished suicide.

Look at them all sniffling "Why didn't she say?" "If only I'd known." Do you see the one bawling in the corner? Didn't return my phone calls for weeks. That other one staring vacantly? Postponed our meet-ups till I lost track.

It is not difficult to understand why a volume of poems on the subject of suicide by an African poet can be a difficult thing. The subject is the last taboo, obdurate and stiff as death. Over the course of the last five decades, various books of poetry by Nigerian authors have concerned themselves with politics, gender and change but not many have examined the inner life of poets and Nigerians. In this new work, a number of points emerge which are of interest to readers and critics.

The first person voice preferred by the poet allows for greater latitude and makes the writing more discursive, more reportorial and it gives freedom to the poet for dramatic monologues. The poet’s descriptions and keen observations emerge many times, powerfully in the collection. Details, of flowers, of people, of the ambient temperature, of mood all serve to elevate the work and to bring the reader into a closer understanding and even sympathy with the poet.

Don't be mad that the waters over my head Were finally more than welcoming. The lagoon doesn't judge. How could it? It holds the secrets to this city. Now it holds mine.

Also, the collection asks questions of the audience in a way which provokes not merely emotive or personal answers. For example, reading through the work, the careful reader may ask why there are no statistics for suicides in Nigeria? The phenomenon of suicide is not alien to Nigeria. The Yorùbá, like the Japanese, do have a long history of ritual suicide but this is reserved for the nobility among the Yorùbá. Professor Femi Oyebode has observed that the permission given by society makes the Yoruba and the Japanese society similar.

Professor Oyebode, who is also an accomplished poet as well as a psychiatrist also observed that the phenomenon of suicide is not evenly distributed in the world. The Caribbean region records very low rates of suicide whereas in a country like Japan the rate is generally higher than the global average. A number of reasons are responsible for these disparities. In the volume under consideration, the author advances some reasons for the suicide and points a finger of blame on society for failing to care and for pretending that all was well when in fact very little was okay.

The truth is that in modern times, in most of Africa and especially in Nigeria we are very bad at providing help for depressed and suicidal people. Nigeria remains one of the countries where attempted suicide is still a crime and the ratio of psychiatrists and psychologists to the general population is very low which means that art and especially poetry may be one way to provide help for a number of people who may otherwise never have access to professional help for the foreseeable future. As this is not a situation that is likely to improve anytime soon and the numbers of Nigerian medical doctors who are leaving the shores of Nigeria for greener pastures in Europe and America is increasing by the day, there is serious cause for concern.

On Attending My Own Wake and Other Episodes is, beyond the lyrical breath it holds and exhales, a work of deontology. Coming from a cosmopolitan poet, the work has made me to venture into the differences and similarities in the European, specifically English, understanding of the human and the Yoruba understanding of the same phenomenon. The very word human has its roots in what is buried. We are the only species on earth that buries our dead. Inhumation has its implications for how we see the world, as contrasted with, say, cremation. The Yoruba word for the human is ènìyàn or èèyàn. That word does not define our species by our bodily end but by our capacity for choice(s). This includes the choice to live and to die and even how. The trouble is that, like the presentation of parrot’s eggs to an Alaafin among the Yoruba, a signal to commit suicide, living itself also has choices which it exercises sometimes against our wishes.

There is incredible will to live in the persona I wanted to talk, they wanted to chat. And the reader is left with a sense of loss when the persona resolves the quandary with:

A respite from my own intensity. My overwrought, insistent self Navigating to the ends of a discourse With people who just wanted a drink.

This is a valuable addition to our literature because it goes where few would dare to go. It is poetry which, in a long tradition pioneered by poets such as Sylvia Plath, Amiri Baraka, Anne Sexton and Hart Crane, treats taboo as just another subject for which humanity must find a language of discourse. The moment of supersession is the choice of the irrepressible persona to be present at the wake, it is at once, deeply subversive of the Yorùbá principle of choice and affirming of the same. The volume presents us with another mirror with which to view both Okonkwo and Unoka. We see the wisdom of Unoka, gifted beyond measure for what fosters community, clearly contrasted with the tragedy of egoistical Okonkwo.

On Attending My Own Wake and Other Episodes throws a challenge we cannot, or should not walk away from. We always will, ultimately, exercise our agency and choice but the task of thinking through our choices and of choosing fellow feeling above the self for the actual good of all is reiterated here for the living.

Tade IPADEOLA received the 2013 Nigeria Prize for Literature for his poetry collection The Sahara Testaments, which has been translated into four languages; in 2009 he won the Delphic Laurel for his poem “Songbird.” A Bellagio Rockefeller Fellow and a juror for the Nigeria Prize for Literature, he also translates poetry into Yorùbá.