The tragic exploits of killer-herders in Zamfara and Igangan, Edo and Ondo; a breadwinner razed in fire for the twin crimes of blasphemy and heresy by self-appointed custodians of faith and morals; orphans dying of the throes of hunger; a woman beaten to death for the womanly crime of being a wife and mother, the endless rain of bombs and bullets at Lekki and Iraq, Kebbi and Kabul, Hiroshima and Pakistan, France and India, to the inviolable dome of democracy in Washington DC: all of these are the news that emblazon the frontpages of digital and traditional tabloids across the world today.

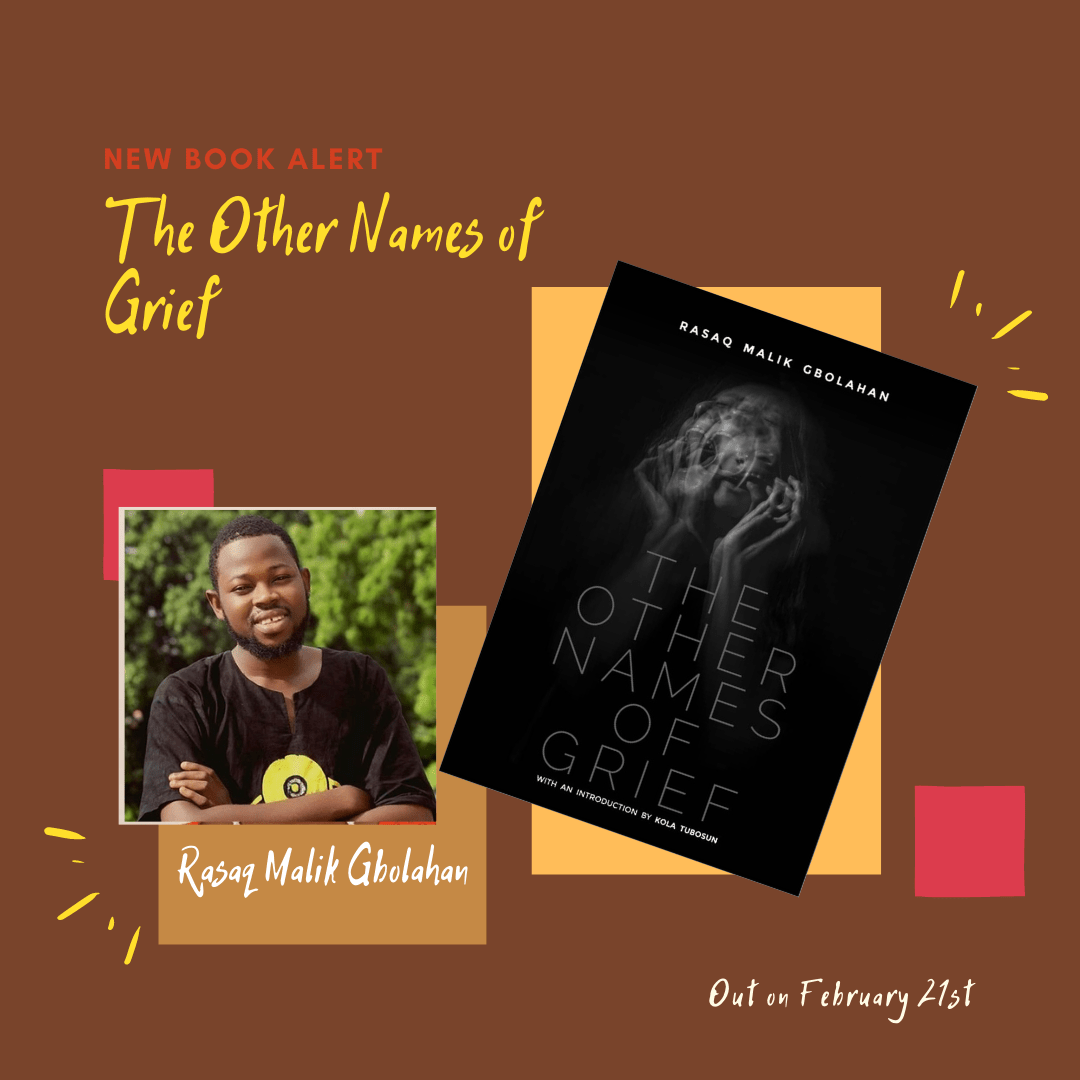

Rasaq Malik in The Other Names of Grief dwells on these plaintive memories, turning the anguish into an epiphany in his new collection. In The Other Names of Grief, we are not only sifted through harrowing narratives of our time, but also we are given an alternative prism through which we can perceive griefs and calamities of this century. We are summoned to identify new names of grief and signifiers of agony. This choice opens new meaning for us wherein we can locate humanity and avert future catastrophe. Rasaq bears witness to this awful trajectory of our time. The poet’s persona has no intent to terrify but to feed us with the troubling tales of the people in our troubling world. Yet, it is not only about telling, but also showing the unspeakable and ugly spectacles of postcolonial Nigeria. Rasaq has been able to do this with deft and lucid application of language accompanied with searing imageries in the new chapbook titled, The Other Names of Grief. The question is, what are the other names of grief? In this compendium of twenty-nine beautiful verses, Malik explains the other names of grief in a way that devastates the most enduring spirit.

Waiting, the first poem in the chapbook, is infused with an urgent tone that chronicles us relatable experiences of traumatic events that a reader has either directly witnessed or seen in the news. The poem paints a troubling image of a people’s attempt to navigate the labyrinth of despair, as they wait and hope to overcome the endless list of grief that defines their daily lives.

Waiting for my homeland to become a source Of bliss, for the wall of bombed houses to resurrect again, …waiting for rain to erase the blood hat stains the street Of my homeland. …Waiting for days without my feet threading on bodies in the street

If the pictures above seem too blurry to elicit the pity of any reader about the global carnival of horror, we can cogitate on the endless trauma of a mother who loses a lonely child to state terror and forced disappearance in Lekki, Gwoza, and Okeho, or Guantanamo Bay in Cuba and the day-light horror that birthed the BLM movement in Minneapolis. Rasaq soberly reflects on all of these related terrors on man by fellow man to provide us the many names of grief which include:

The register that bears the names of people shot and buried Like some black boys in Missouri, Baltimore etc The darkness that chokes the life Of a woman who still longs for the arrival of her dead chill

That is not all, the poems in this collection reveal this poet as a firm believer in writerly responsibility of knowing and making the readers know. Arts of Poetry is a veritable testimony to this notion. The poem relays to the readers – and equally to writers – what should serve as an inspiration for anyone with a burning desire to write, especially at this perilous time. Arts of poetry seems an intertextual rework of Horace’s Ars Poetica, an essay the Roman poet advanced as a treatise on the techniques of writing. While Horace’s emphasis was on form, Rasaq’s Arts of Poetry dwells on the subject matter of a global community in ruins and how this can be adopted as creative muse. To be a poet is a onerous calling but:

Sometimes, it is the tragedy that molds a poem Like Gaza, like Burma, like Paris, like Nigeria …Once I watch as flames drift across streets, Reeking of bodies left unburied in distant countries.

Similarly, we are nudged to the reality that state war, terrorism, domestic violence, and their destructive impacts as a global conundrum. Malik universalises these unpalatable experiences. Terror has defied the boundaries of time and space. The binary notion of the empire and the Eldorado has crumbled to the vampiric nature of human-induced terrors in their varying degrees. If it is raining here, it is raining elsewhere. This shared sense of doom has turned the world into a metaphoric warfare and this chapbook has captured the situation without a fog of ambiguity. In the poem, “What Else”, we are faced with the bitter realities that Paris is dead, Nigeria inhales the smokes that rises from the bodies of her citizens, Syria watches as bombs drop corpses like dung of horses on her land while America desecrates her own symbol of liberty with the blood of her citizens. What Else and where else is safe in the world? This makes us appreciate, in spite of the worries evoked by the stories in this collection, the cosmopolitan identity of the poet as a Nigerian, African and citizen of a global community at war with itself.

Other poems in the chapbook project different but related events of our ailing world. The poem “Another Morning” is the poet’s euphemistic rendering of another day of mourning, “What My Father Says Every Night” echoes the angst of a people going to bed with a faint hope of waking to see the next day, or the fear of waking to another deluge of tragic news. Imagine a world where people go to bed and hope that they do not have to search for our beloved at the scenes of explosion or wake without smelling corpses that is, if the sleepers are fortunate to survive another night of terror.

Moreover, Rasaq takes a critical swipe at domestic violence and marital tyranny visited on women. Bodily abuse, sexual predation and economic subjugation have become permanent ordeals of women in developing countries. Justifying the need to identify gender violence as part of global terrors, the poet brilliantly highlights the many troubles faced by women, both physiologically and culturally and how these have become useful tools of oppression wielded by the patriarchal tormentors. He understands the magnitude of violence against women and he is committed to voicing the imbalances as seen in the poems “Becoming Women”, “How My Mother Spends Her Night” and “Firdaus”. The latter celebrates women who fight to survive society-orchestrated gender limitations and do not cave in to the generational oppression of patriarchy.

Yet it is not all gloom as the title of the chapbook may have suggested. Rasaq knows that the principal responsibility of a poet is to provide delight, and he has that provided in excess in this collection, thereby giving cathartic moments for readers who may have been terrified by the many lacerating revelations of man’s inhumanity to man that saturates the chapbook. The poems “Beloved”, “This Country Will Break Us” and “In Your Absence” take on the subject of love and through them Malik diffuses the earlier tensions built in the collection. The poems point to the fact that despite the deftness of Rasaq in handling the subject matter of war and trauma, he is naturally a poet who loves love and can capture it in lovely verses.

In the end, with limpid language, tactful tone and creative craft of themes, this chapbook becomes a confluence of beauty and trauma, of love and hate, and of perdition and hope. Reading and reflecting on its poetic meditation can trigger a shared sense of pity for the displaced, the marginalized, the troubled and the traumatized; and most importantly, it is capable of opening a window of conversation to heal our wounded world.

Akin Oseni is a graduate student at Bowling Green State University, Ohio, United States.