(When words paddle their way from English to Korean)

A new 240-page book containing the Korean translation of a selection of my poems found its way into my hands a couple of weeks ago – after waiting for six months in the parcels vault of the Nigerian post office. Long-coming but enthusiastically embraced. An ample, diligently selected volume from four decades of my writing career, these poems cover a cross section of my thematic preoccupations and stylistic peculiarities. As noted in the appreciative foreword below, the translator’s choice of poems is representative and admirably professional. But beyond these virtues, there are lessons I have learnt from the long, complex, and frequently confounding translation process that are worth sharing with readers, considering their instructive instantiation of the role of literature in cultural diplomacy, international understanding, and the discovery and cultivation of socio-political affinities where we might previously have thought that none existed.

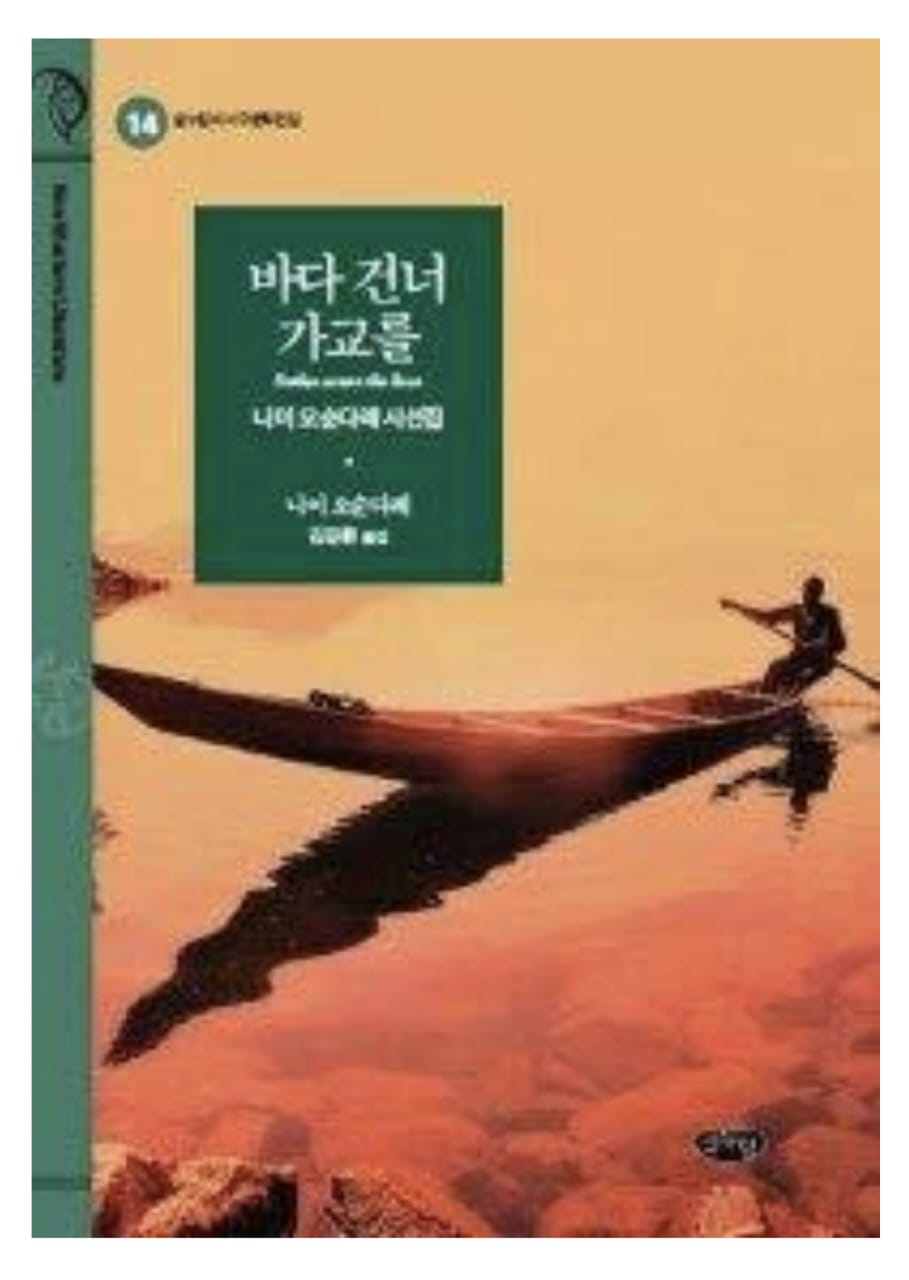

Bridge across the Seas, a line chosen from one of the translated poems, which serves as the English title of this book, is an felicitous articulation of the purpose of the translation project and the book itself., a purpose which speaks to the Korean policy regarding the de-marginalization of non-Western literatures, the broadening of the scope of the literary arts, and the strengthening of their power as media of international understanding and intercommunication of ideas..….. The rest of this story is more eloquently told by the piece below, my brief foreword to the book, written expressly at the translator’s request:

Seven Cheers to the Bridge Builder (The Foreword)

The ultimate, decisive inspiration for this brief preface emerged from our gathering at the Book Café, that busy joint founded and managed by Woo Soo Kim in the port City of Busan. It was a Friday evening, the 11th day of October, 2019, and the venue was brimming with the cream of Korean literati, university professors and their students, book writers, book readers, and book lovers. On my part as guest writer whose works constituted the subject of the evening’s deliberations, I was securely surrounded at the front table by four members of this formidable literati one of who kept us all deeply engaged by providing an intellectual exploration of my poetry through an interpretation of some 27 poems plus their Korean translations, in a splendidly published booklet specially put together for the evening’s event.

One of the most memorable issues raised at that Bussan gathering is the fate of literary works in the non-major languages of the world vis a vis literature in the ‘major’ ones –particularly the way global literary prizes have always gone to works written in the ‘major’ languages. This practice of advertent or inadvertent neglect has widened the long-standing gap between the languages of the powerful and privileged and those of the powerless and marginalized. How, then, do we get to discover the tremendous range and richness of works written in local languages remote from the powerful eyes and ears of the judges of ‘global’ literary taste and value? How can we enable the rest of Humanity to share the meanings and methods of works produced in languages beyond the comprehension of literary canon-makers and their authoritative endorsements?

Herein comes the necessity – and inevitability – of the act of translation as bridge-building and the softening of the soil for the seeds of pan-Human understanding and enlightenment. For, translation does not only enable the discovery of areas of similarity between languages and the cultures from which they spring; it also makes possible the apprehension and appreciation of their areas of difference, and a possible management of the politics (or politicking) that frequently comes with that difference. Perhaps no other human attribute is more jealously territorial than language; none is more indigenous to the biological, psychological, cultural, epistemological peculiarities of its user. It is the several attempts at the exploration of this indigeneity and negotiation of this territoriality that make the work of the translator so challenging and so essential. It is also why a genuine work of translation is an exercise in interpretation and comparativism, while the translator functions as the vital connector and positive enabler.

‘Connector‘ and ‘enabler’: this is basically what Professor Joon-Hwan Kim has been in this generous translation of my poems into Korean.. His meticulous and highly professional questions and queries in our correspondence during his translation process took me back to the creative origins of many of the poems, while his English interpretation of some of the lines actually surprised me with nuances and insights locked up in the inner recesses of the words. Translation issues arising from my use of elliptical syntax and extended repetition, my deliberate play on the sound and sounding of words, my penchant for neologism and creative rejuvenation of old words, my essentially transgressive attitude to words and ideas – all these came up in our correspondence, and left me with a keener, more self-conscious consideration for the communicative potential of words and their syntactic arrangement. Without any doubt, it must have occurred to my translator that he was translating poems written in English but with a strong Yoruba deep structure. For as I said in my essay of many years ago, in Yoruba, my mother tongue and first language, poetry is music, and music is poetry; the listener’s ear is forever close to the poet’s mouth *.

It has been both challenging and exciting to work through many of the lines with the eagle-eyed Professor Joon-Hwan Kim! I thank him for his patience and wisdom; just as I am grateful to Professor Jaeong Kim for the creative impetus that led to the translation project, and his warm, enabling enthusiasm. And to all the people whose effort has resulted in making my poetry accessible to the Korean audience, I say Mo dupe o (I thank you indeed).

________

*’Yoruba Thoughts, English Words: A Poet’s Journey Through the Tunnel of Two Tongues’. Thread in the Loom: Essays on African Literature and Culture. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press,2002, pp.115-131.

Niyi Osundare is a leading African poet, dramatist, critic, essayist, and media columnist. He has authored 18 books of poetry, two books of selected poems with several literary laurels to his credits.