Ademola: Somewhere, Chinua Achebe says, “there is no story that is not true.” While this is a profound assertion, it also speaks, in my opinion, about the stringency of the fiction-nonfiction rules. As someone whose first book, Satans & Shaitans, was a fictionalized account of a deeply researched feature of the current Nigerian society, what do you think about blurring lines, about breaking boundaries? How many boundaries do you think writers are allowed to break?

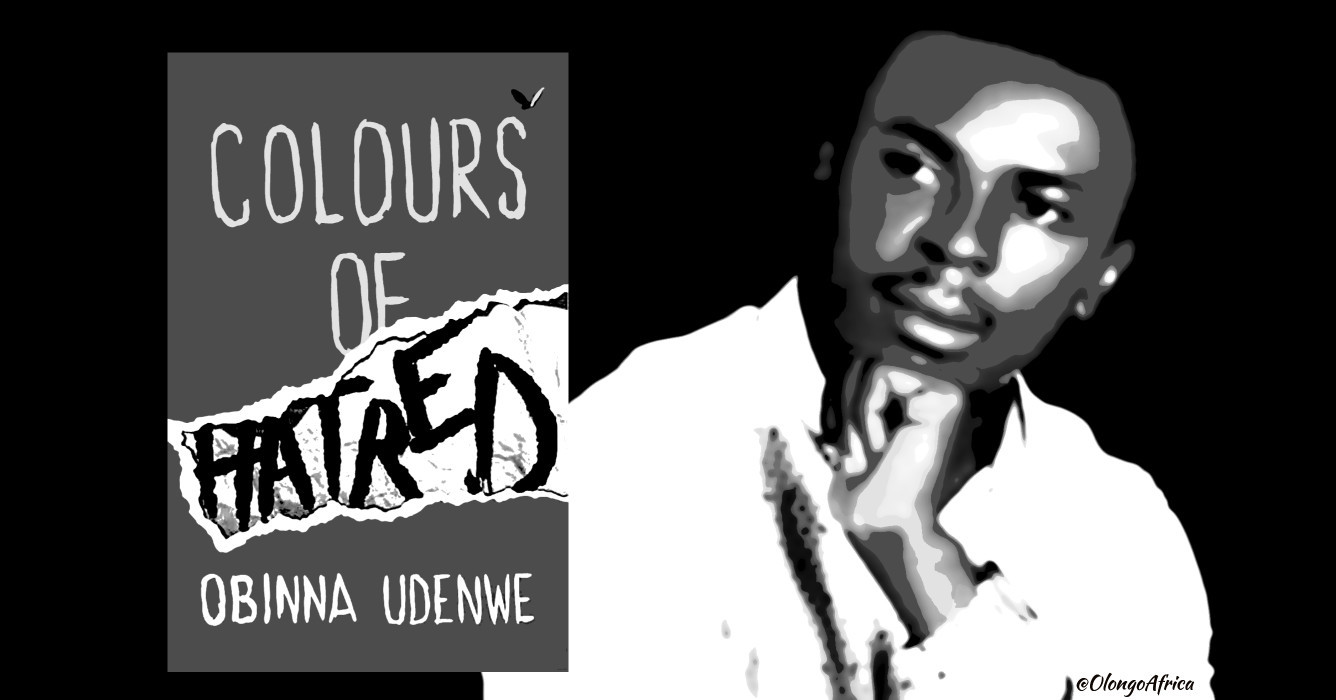

Obinna: The line between fiction and non-fiction is very thin, I believe, and for some writers, myself inclusive, I pay careful attention to the happenings in my society and around me, so that when I write, I find that most of what I had observed or heard people say or do, unconsciously or consciously seep into my writings; in my novels, most of my short stories, as well. Take for instance my short story, ‘John 101, or The New Ridiculous Way to Commit Suicide and be Famous’ which won the Prairie Schooner-Glenna Luschei Prize – in that short story, I was inspired by an incident that happened at a post office one day, where a man had come to post a letter to Barack Obama, it inspired that particular short story. For Colours of Hatred and Satans & Shaitans that you mentioned, the story, though fictitious, derives its strength from real historical events, carefully researched and made to form the backdrop of the stories. For Satans & Shaitans, it is as if the fictitious plot is gradually unfolding before our eyes in today’s Nigeria – Satans & Shaitans is becoming our reality, and it is scary. Most readers have noticed this and some are beginning to say that I was a prophet. Someone dared to say that someday I may be invited for questioning by the secret police. As outlandish as this may sound, I fear that it may soon come to that. Concerning breaking boundaries, I think there are no restrictions, if you can do it well, you are free; you can only hope the outcome turns out great.

Ademola: In a 2016 interview with Black Letter Media, you mentioned how documenting stories started when your uncle bought you an exercise book, and you just wrote down all your imagined stories, which, in that sense, is fiction. So, in a way, we can say that you started with writing fiction. But, I want to know, because we agree that stories aren’t formed from a vacuum, I want to believe that, even though you imagined those stories, they could have as well been replicas of true life activities. In that sense, when you eventually started writing officially, after your uncle passed, and when you must have become somewhat more informed about the art of writing, did it change your perception of what fiction and nonfiction is? Did you draw a line? And, if you did, how were those lines formed, for you?

Obinna: They might be a replica or close to a replica of true life activities for as I had mentioned I am a careful observer of my environment, but this was many years ago, when I was a teenager. I don’t think I remember any of the stories I wrote back then to know what they were about, how much fact and reality that were in them, but they most likely were fiction, they should. So you can say that I started first with writing fiction and you’d be right. I recall that the first time I wrote a creative non-fiction work was in 2010, after I was part of a group of select young democrats sent to Cameroon to understudy their democracy and then after every of my trip abroad and around the country – these accounts I was collating into a collection I titled The Diary of a Journey Walker, but sort of got tired of writing them or developed a block, well, I might have started travelling a lot at some point to keep account of all of them, so quit. Well, someday I might pick up the collection again, who knows. About drawing lines between fiction and nonfiction, I believe that if you try to become conscious of this and to consciously write in that way, you may end up producing very shallow works. For me, if I have a story idea, I think it over and through, sit and start writing. Take for instance, Holy Sex. So someday I came across a news story about a pastor in one Middle East country or so who made his congregant swallow his semen and claimed it was holy milk and voila I created the stories that became the series and later the novella, Holy Sex. Then something remarkable happened, while the stories were being created or newly published, a Nigerian popular pastor in Abuja was accused by a Nigerian lady who lived overseas of almost the same thing. Recently, a popular celebrity also accused this same pastor of rape – so one can argue that Holy Sex is fact clothed in fiction to represent Nigerian randy pastors and wouldn’t be wrong, but I didn’t set out, at the time, with a back-story of a particular randy Nigerian pastor in mind.

Ademola: This is also bearing in mind that Colours of Hatred is set against a background of real events in Sudan and Nigeria, and, even your debut novel, Satans & Shaitans, hinges very actively on Nigeria’s ongoing terrorism and electoral tensions. In that regard, I would say you like to tether towards marrying real and imagined stories into a body of work. Is this an extension of literary classification according to your own understanding of it, like some would say what you do is “faction,” a marriage of facts and fiction. Is this something you’ve deliberately decided to work around? Or do you just move with the story?

Obinna: Many writers plot their story. They sit down and come up with a story structure and character attributes etc., etc. They do the research first then start writing. I don’t work like that. I am driven by a plot or a character, whichever comes to me first – for Satans & Shaitans, it was the plot that came to me first and the characters grew around it. For Colours of Hatred, it was the character Leona and the plot developed around her. So when the idea comes to me, I sit down in front of my computer and start writing the story straight from my head. As I write, I give the characters names straight away and build them up etc. After the first draft is ready, I go back to carry out research on aspects of the story that need investigation, then flesh out the story – this can happen over and over again. Take for instance, Colours of Hatred, I first wrote it in 2009 at the age of 21, then went back to do the research that built it up. Usually, I don’t say that I would write this story to be a mix of fact and fiction. No. I just write the story and flow with it and when I re-read, I decide what to do with it. So I just move with the story.

Ademola: You once mentioned that Satans and Shaitans evolved from a romantic novel to a crime thriller. And now, Colours of Hatred is almost a romantic crime thriller. Writing this, what was the intention? Did you want to write another romance and love story with a tinge of crime? Or did the plot just evolve from what you initially imagined?

Obinna: When the story of Leona came, I wanted to tell the story of a young, beautiful girl in a family that allowed itself to be torn apart by hate and what would become of this beautiful girl at the end, and I wrote the story. At first it wasn’t Colours of Hatred, it was slightly different, and with a different title. In 2014, I was admitted into the Ebedi International Writers Residency and while there, I deleted over 40, 000 words from the already completed novel and reworked it to become what it is now. So as I was writing it, the story was taking the shape it has now. I was only running to catch up. That is why the ending is the way it is. At a reading with the Liber Book Club, Asaba, someone asked me what became of Leona, and I said I did not know. They found it difficult believing I don’t know if she is alive or dead. But truly, I don’t know. Regarding the classification of Colours of Hatred as a crime thriller, this first happened after the Nigeria Prize for Literature shortlist – it surprised me that some readers see it as that. It gave me a fresh perspective to the work and I was tempted to re-read it. Readers interpret literary works differently and most times the way they see them differs from the way writers do. In furtherance to this classification, one reviewer, I think Michael Chukwudera it was, wrote that Colours of Hatred is a good way to blend crime thriller and literary fiction, and supported his assertion with great points – it surprised me. It intrigued me.

Ademola: How do your characters come to you? In Colours of Hatred, for instance, Leona is not the most likeable personality; from one bad decision to another. The first question is, how much of real and imagined is Leona ‘s personality? Because, for a kind of fictional memoir laced with crime and war, many writers, I believe, would have opted for a plot-driven narrative, where the story flutters between war and crime and loss and death, but you hinged the story on your characters, who revolved, visceral and vicious, in each page and chapter. So, I am curious as to how you created the characters.

Obinna: Leona is named after my long time friend, Leona Taylor of Liberia, but this is in no way her story, at all. The Leona character, aside the name, is entirely imagined. Entirely. As for her personality and attributes, they are imagined, but it is possible, very possible that one may find someone or other, somewhere in the world, who shares the same personality as our darling Leona. And as you mentioned, Leona is not my favourite character – I think she is a weak person who does not know how to stand her ground and say no when she should say no. The story revolves around the characters and I did this because I set out to write a story of a young woman and her travails, and of women and their troubles in a patriarchal society where men see women as objects they must conquer, sacrifice or use to achieve their own end. Besides, because the story is told in Leona’s eyes, it cannot be plot driven because to make it work that way you would have to write the story using the third person. But in this case, Leona who is narrating the story doesn’t see everything, doesn’t know everything, unless those things she hears, or told to her or she learns by eavesdropping, you see?

Ademola: As an essayist, myself, I am interested in unravelling the relationship between people and places because, in my opinion, humans are mostly products of the communities where they experienced the things that contribute to their eventual humanity. That’s why I want to know, why did you decide on Sudan for this novel? I mean, in Satans & Shaitans, there were mostly vague mentions of countries in Europe, but in Colours of Hatred, you situated the story between Sudan and Nigeria with a backdrop of War, so why Sudan? And why now?

Obinna: When I created the Leona story, I wanted to create a back story of an experience that becomes the backbone of her family’s trouble, then one day, I was watching the news and saw the war in Darfur, Sudan and saw women carrying babies on their backs, with their belongings tied up on their heads, trekking long distances, and it occurred to me that these women were escaping a war created by men, mostly. I thought, why not use this as the back-story I needed. So I reworked the story to set it partly in Sudan, that was towards the end of 2009 or 2010. So when I went to the residency and decided to change the story, I did more research on Sudan and saw the similarities with Nigeria – they are quite striking – I deleted a huge chunk of the story and reworked it. You see, as at the time, South Sudan hadn’t gained independence and when it happened afterwards, it marveled me.

Ademola: So, there’s been a conversation about African writers commercializing their trauma, and showcasing war and famine and unrest, which is exactly what the West wants. Considering that Colours of Hatred is hinged mostly on the Civil War in Sudan and Nigeria, did you feel a sense of conflict that this story, this novel, might tick the box of trauma/Poverty porn? Has that ever bothered you? Because, it has me thinking: do we have to censor what writers write about, or maybe we need more stories?

Obinna: Oh, is it really what the West wants or they just want to read a story that speaks to their heart? How do we know it is what they want? Many people are attracted to stories that prick their emotion and most times, these stories are ones that address a human issue or other and in Africa, stories about war and poverty abound and writers tell them. There are stories from the west that could be classified as poverty porn but they are not – people just call them great stories – think of Colour of Water, think Angela’s Ashes; think The Colour Purple etc., etc, and there are many that could be said to be ‘trauma porn’ but we don’t give these classifications. Why are we quick to classify African stories as such? I think it is stupidity. I don’t think any writer sets out to write a story about poverty and penury in Africa with the intention of pandering to the west. When I set out to write Colours of Hatred, I did not think anyone would classify it as ‘trauma porn’, permit me to use your words, because the war story is used only as a background or back story. You can’t call Colours of Hatred a war story the way you’d refer to say Ian McEwan’s Atonement or Sebastian Faulk’s Birdsong or Frederick Forsyth’s novels. And it is definitely not poverty porn, in fact, some people have said that I write only about middle class or elite families. For me, I tell a story as it comes to me and whatever the story turns out to become, I don’t care. Take for instance, the ending of Satans & Shaitans which some people have argued has lots of the characters dead, they say I should not have written it that way. It surprises me, because that was how the story came to me.

Ademola: You have always been heavy on research. And, honestly, I couldn’t help but notice the details that went into Colours of Hatred, especially with regards to Sudan. I want to know, how much travelling did you have to do? Did you have collaborators from over there who helped with even minute details? Why I’m asking is because the novel also travelled through 80s and 90s Sudan. How did you achieve this possibility? I remember the description of Abu Jamal Beer.

Obinna: Whatever is worth doing, is worth doing well, they say. You talk about 80s and 90s Sudan and forget that in Satans & Shaitans, Islam takes centre stage, yet I am not a Muslim. Did I become a Muslim for a while to write the story?

Ademola: Let’s talk about spirituality and priests in your novels; from Satans & Shaitans to the Holy Sex series to Colours of Hatred, you’ve always infused confessions and Catholic priests in your stories. Is this a reflection of your religious/spiritual subscription?

Obinna: I have a lot of priests as friends. And I hate pastors, I think most of them are worldly, deceitful, fake, fetish and stupid – especially the ones they call new generation. Today, someone selling wares at Yaba and not making enough money to get by may wake up and announce that God has spoken to him and tomorrow he rents a church somewhere down his street. Now everyone claims God is speaking to them. I wonder how God speaks to them – it bothers me. You should read Olukorede Yishau’s In the Name of our Father or This Church my Shrine to understand the rot that is Nigeria’s Pentecostalism. It is a shame and I think we should do what the Rwandan government is doing. In fact, I believe that the reason we do not holding our government accountable is partly because these pastors have made most Nigerians develop an idea about some place called Heaven where we would be consoled for all our travails on earth and that it is okay to suffer on earth, that it is God’s will, as long as you continue to run the race for salvation – the race to inherit a better place in the afterlife. It is one of the greatest calamities that have befallen this country. Aside being close to priests, I was a mass servant for ten years, growing up, and understanding the way the church works and the way priests think – I believe they are one of the most intelligent people in the world – I also believe most of them are narrow minded, which causes them to take some very stupid decisions – think of the priest, Fr. Simeon in Satans & Shaitans.

Ademola: In the course of starting the process to write Colours of Hatred, which came first to you between the war and the estrangement of love and family? Mostly, wars disrupt the course of our existence, but, beyond that, you reflected the tribal (religious) differences that have disrupted the two countries where the novel happens. What were you, initially, trying to achieve: using wars to show how humans are callous or using human callousness and criminal tendencies to push the destructive impacts of war? The novel does an excellent job of straddling both. But, as someone who is also hopefully writing a book, I’m trying to understand practical details about plotting, especially as it concerns blurring the borders of fiction and nonfiction. I mean, I’ve always wanted to know this particular aspect of writing a book. Half Of A Yellow Sun and Festus Iyayi’s Heroes piqued my interest about the process of writing the other details of war.

Obinna: For Colours of Hatred, I wanted to show how trauma can come into a family and mess it up. In this case, it was the experience the Egbufors had been in war torn Sudan and that tore them apart as a family and I wanted to show this without making them go through the war as Adichie did in her book or as Uzodimma Iweala did in his Beasts of no Nation. Some novels try to make war their central theme while others make it a background, a shadow, like Atonement by Ian McEwan that I had mentioned earlier. You should read it. The story is about a young woman who commits the sin of slander and how this changes the life of her older sister and the sister’s lover, then at the course of the novel, war happens yet it doesn’t change the strength of the story which lies on the characters. In Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun you’d notice that it is entirely about the Biafran war. In writing about war in novels, I believe it is what you set out to do that determines how the story turns out. What kind of story do you want to tell?

Ademola: Minus the fact that Nigeria is a larger entity, she has always shared unmistakable similarities with Sudan: Civil wars, tribal wars, religious division and the writhing tensions. So, throughout the reading of Colours of Hatred, those similarities were very visible, visceral, even, which has me wondering, what was the decision behind deciding to make those two countries the settings for Colours of Hatred? Was there a real story that connected the two countries (and you just fictionalized), or was it that the two countries suited the narrative you intended to tell?

Obinna: I mentioned how I came about Sudan and how it fit the story I wanted to tell, especially as while researching the country’s history I realized the similarities with Nigeria’s. So yes, they suited the narrative I wanted to push.

Ademola: I couldn’t help but notice some instances of religious indifference; critical and rebellious thoughts by some of the characters: for instance, Lemya mentioned some of her reservations about the draconian stringency of Islam, while Leona, on the other hand, Leona mentioned her indifference about priests being celibate. But, most importantly, you also showcased religion in a positive light, creating an effective, diverse and really dynamic sequence of events. We mostly believe that characters, sometimes, say the things the authors want to say, mirroring their view and perspectives. Was this the same for Colours of Hatred? Those unpopular religious standpoints, was that you and how you feel about some religious elements, or something you devised to make the characters as rounded as possible?

Obinna: It’s neither here nor there. Sometimes what characters say in books mirror the perspective of the writer on an issue, but not at all time. Mostly the writer wants to make sure the characters are well developed enough that they can have good, believable conversation, so if it’s a well-informed character, you’d want to ensure they talk intelligently and if it’s a character that isn’t intelligent, you also make them think like one who isn’t intelligent. If you have read Abi Dare’s The Girl with the Louding Voice you’d notice that is what she did. In the sitcom, Jenifa, you find the Jenifa character’s voice is very in tune with her level of development academically and socially.

Ademola: Before now, especially with Greek tragedy, which, arguably, was a major influence on African dramatic tragedy that existed with the first generation of writers, there was the unity of place, time, and action. However, considering Ngugi’s vocal stance on decolonizing African Literature, and Achebe’s fearless domestication and Africanisation of the English language, many things have changed with how African writers perceive Literature, especially the novel. By your reckoning, what is an African novel? Colours of Hatred took place over decades, in different African locations, with many actions happening simultaneously.

Obinna: There is nothing like an African novel or American novel or Chinese novel. A novel is a novel. A story is a story but sadly, we live in a world where we seem to cease breathing if we don’t categorize and give names to things. Take for instance Nigeria, we categorize people and the first thing that comes to mind when we meet people is that we ask them the state they come from, and stereotype them in the process. It is the same thing we are doing with literature. We categorize it and say this is an African novel, an Asian novel – now, we even go as far as breaking it down to say South African novel, Kenyan novel, Nigerian novel. It doesn’t make sense. What Achebe did with his works, as you rightly pointed out, is enough lesson that should have taught us that a novel is a novel and that one could bend the novel to suit their taste, but it is a shame we did not learn this lesson over sixty years after Achebe wrote his earlier works.

Ademola: So, when you started, did you have it somewhere at the back of your mind that you wanted to write THE African novel? Or did you just want to tell a story and write a novel?

Obinna: What is an African novel? So do we call Colours of Hatred an African novel because it is written by a Nigerian or because it is set in Nigeria or both? Who defines this categorization? Do we call Chris Abani’s The Secret History of Las Vegas an American novel or an African novel? If we say it is American, is it because it is set in the US? Do we categorize it as African because Chris is Nigerian? What about Mbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers? etc. I find it difficult thinking around this categorization.

Ademola: Would you want Colours of Hatred to be classified as an African novel? How would you want it to be classified?

Obinna: I would want it to be classified as a novel. My friend Karen Jennings has written a blockbuster, An Island – how do you classify that book?

Ademola: The place of the mother-tongue is seen not only to be very crucial and central to the encapsulation and expression of human thoughts and ideas but also a validation of his identity and existential essence. How do you navigate this, with your experiences, which might have transcended cultures and traditions, how do you retain your mother tongue?

Obinna: This is a very interesting question. I believe that mother tongue is very important in helping to give us identity and in helping us to develop better fluency in other languages. My mother tongue is Izii spoken by the Abakaliki people, with striking similarities to the Central Igbo language but early scholars, Paul and Inge Meier and John Bendor-Samuel who studied the language in the 70s proved that it is a distinct language of its own, different from central Igbo. I speak it to my children because I want them to grow up having a good sense of identity and culture – I believe that you cannot really be well versed in your culture if you do not know your language – I want them to be first, Izii, before being cosmopolitan or other terms we throw about these days. So you retain your mother tongue by speaking it, by teaching it to your children, by embracing it with your shoulders raised high.

Ademola: When writing, what do you think? Do you think in indigenous languages? From my experiences reading Colours of Hatred, there was an exciting and enjoyable Igbo aura, or atmosphere, which, even though the novel is somewhat cosmopolitan, saturated the page of the book. So, how much, and how less, of an Igbo did you have to be to accomplish the literary bliss that is this second novel.

Obinna: I am proudly Igbo and when I write I want readers to know this. But if a character is Igbo and talks as Aunty Agii does in Colours of Hatred, you must make sure the switch between English and the other language she identifies with is prominent, same with say if a character is Yoruba or Muslim who must use some Arabic words once in a while, like in Satans & Shaitans. And when I think, I think in Izii or Igbo. I communicate with God and my ancestors in Izii or Igbo. I express anger and worry in these languages. English for me is like one wearing their clothes inside out.

Ademola: I remember, some years back, myself, Igoni Barret, and Chris Abani had a conversation at Freedom Park, about his novella, Becoming Abigail, and one of the most important questions that resurfaced was about men writing women characters and how much of ‘womaning’ Abani had to do to be able to unequivocally express the Abigail character well. So I want to ask you, Writing the Leona character, both as a child and as an adult, how did you achieve that? Did you have to particularly study a female person? How much of the character is real and imagined? How were you able to capture the mannerisms of a female child and an adult?

Obinna: Oh, I have read Becoming Abigail and I think it is simply a sophisticated work. There is this argument that men who write women characters must try to ensure that they capture the experiences of women well without distortion but we don’t seem to hold female writers to the same responsibility. I write a lot about the opposite sex. I am one of the writers who make my lead characters female, both in novels and short stories. So I try to ensure that the representation is roundly captured and for the Leona character, I created her in my head and nursed her there for a long time before writing the story. Then there is the strong need to be a careful observer of one’s environment. I also have a lot of female friends who are so close they share all kinds of details with me. As regards mannerisms, I have observed women for a long time to know how to attempt representing them in stories. But then someone in a recent book reading I had argued that the experience of sexual molestation Leona suffered as a teenager isn’t possible and I laughed so hard, because many people still live in a bubble where they believe the world is all innocent and rosy. A lot is going on around us, our kids are experiencing all kinds of things but we parents aren’t paying enough attention. We need to pay more attention.

Ademola: As someone who has published two novels, I’m sure there have been both positive and negative reviews and criticism. I understand that some must have been borne from a critical interrogation of the text, while others might have been, at best, borne from resentment, I believe. How do you, as a writer, navigate this?

Obinna: Now everyone is a book reviewer or art critic. Especially on social media. It is laughable and saddening at the same time. For me there are book reviews and there are commentaries. And I think in Nigeria we are doing more of commentaries than reviews. When you think about reviews then you have to talk about what Paul Liam does – he is one of the best so far. There are people who when I read their supposed reviews, I laugh because they just show how shallow their reading has been. You can’t be a good book reviewer if you haven’t read widely. Someone reviewed Colours of Hatred and said that the ending doesn’t work, that it isn’t conclusive. Must the ending of a novel be conclusive? Besides what you term inconclusive ending, to the author, may be very much conclusive. Most times, the author ends the story where the story wants to stop and allows the reader to continue the story in their mind, ruminating over it, pondering and interpreting it the way they want. A good novel isn’t a fairy tale where at the end, the prince and princess walk hand in hand and kiss passionately and live happily ever after. That is lazy writing. It is for children.

Ademola: How much of critical is critical and should be paid attention to?

Obinna: I think a good writer should pay attention to all – reviews, commentaries, critical essays etc., etc. The writer should want to read various perspectives to his work without allowing these reviews or commentaries to affect him. I am one of the writers who believe that reviews are important because they help you get peoples’ perspective and even help you improve the craft. Some writers are sad when they read reviews of their work, they pick up a fight. Like Chigozie Obioma did a few years ago.

Ademola: So, how should writers navigate reading critical opinions about their work? Would you recommend even reading them?

Obinna: Of course, you should want to know what people think of your creation without allowing the praise to get into your head or the ‘bad-mouthing’ make you despondent. Besides, what one reviewer terms a bad work, to another could be a classic. Examples abound. I read reviews of my work and laugh. If a reviewer says my work has this or that fault, say the ending isn’t conclusive, I shrug and move on because the work is out there, birthed already – how often do you see mothers cry when they hear that their children have an oblong head or rounded nose or bow-leg?

Ademola: Personally, I’m very skeptical, sometimes, because criticisms, in my opinion, are rather subjective, and are mostly a product of the critic’s sentiment. For instance, Helon Habila, in his Review of Akwaeke’s Dear Senthurian, had this to say:

“…How do they do it, where do they get the time? Especially since they often seem to be on social media arguing with other writers (see the recent row with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie), former friends or literary prize organizers. Emezi clearly knows the value of high-profile social media fights: they get people talking about you.” If you ask me, this is an example on how not to review a literary work. Because it barely engages with the text, but found a way to insert personal jabs.

Obinna: Examples abound which attest that Helon is not a good reviewer. I think he should just stick to writing as he is a good novelist.

Ademola Adefolami is a storyteller, curator, and content strategist. His writings have been published in New Orleans Review, Anathema Magazine, Entropy Magazine, New York Literary Magazine, Ynaija, The Rustin Times, Folio Nigeria, Ebedi Review, and Ktravula, to mention a few. He shares his thoughts about the world on twitter @Lagos_Tout.