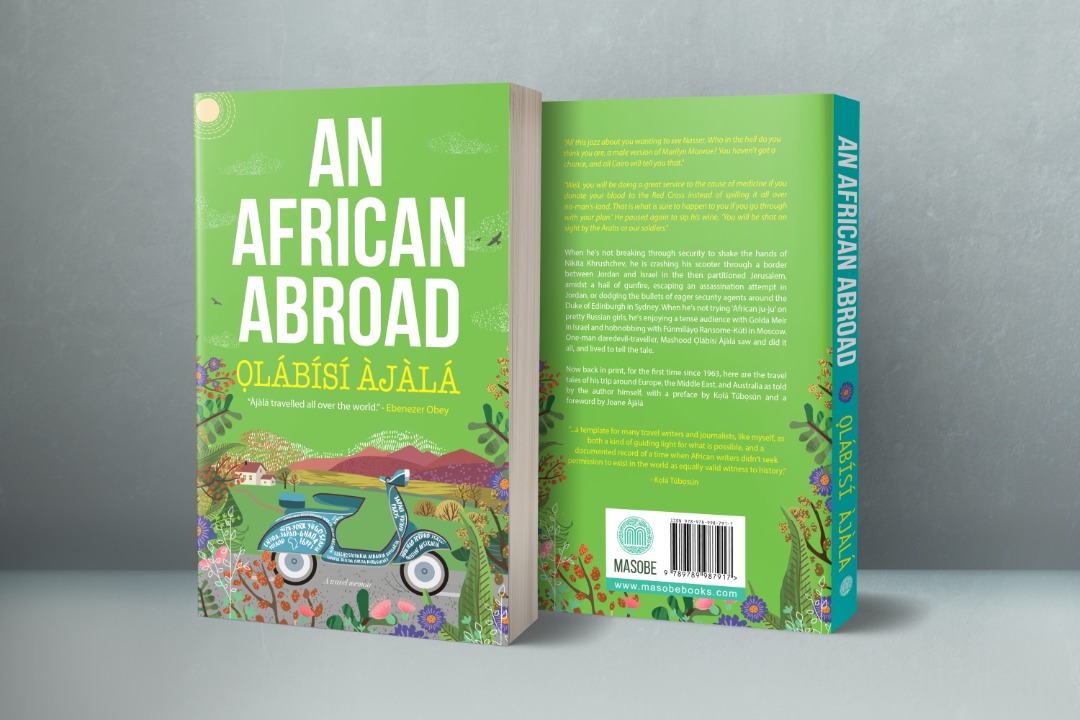

To a generation of Nigerians, the character Àjàlá might as well be an urban legend. Fictionalised in film, memorialised in music and romanticised in folklore, Ajala has become a common noun, a term in popular Nigerian usage for something part Don Quixote and part Don Juan. Over the last few decades, Olabisi Ajala’s legend has largely muddied the more earnest aspects of his legacy. For this reason alone, it is a joy to finally see the republication of An African Abroad, the travel memoir of this pioneering explorer from Nigeria.

Coming circa sixty years after the first edition, the new edition promises to introduce a new generation to the world of African travelling through a large portion of the world on a scooter in a time of major global tensions. With almost overstated confidence but sensitive eyes, Àjàlá explored the world in a manner that reprises an era of African adventurers quite different from what we have been used to in the now saturated travel blogosphere. Tom Mboya, the late Kenya nationalist and labour activist who wrote the introduction to the original edition, saw the work, in large part, as another manifestation of the newfound confidence and expressiveness of Africans in keeping with the spirit of independence.

Current readers of the book would notice how much the world has changed to a large degree since the 1950s-60s, when Àjàlá travelled, and how things nonetheless remain the same in many respects. Visiting Israel, he compares the tensions in partitioned Jerusalem to cold war era Berlin. Of course, that comparison would not be apt today. Compared to the European city, the ancient Middle Eastern city still retains its image of a boiling cauldron of ancient clans and faiths. The promise that the momentous events in global politics of the early 1990s—the collapse of the Berlin wall and the handshake between PLO and Israeli government, for example—would yield long-lasting peace has sadly not been realised in Israeli-occupied Palestine. Yet, as far as the cold war goes, hostilities produced by the current isolation of Russia from the rest of Europe would make the conversations that Ajala had with Nigerian students in the hostels of Russian universities not altogether dissimilar to what might come out of any interaction with the African students who had to be huddled out of Ukraine a few months ago. And that, sadly, includes racial undercurrents in officially welcoming spaces.

As a traveller, Àjàlá would be what happened if Forrest Gump were fully conscious and somewhat deliberate. He did not just stumble along in his otherwise romantic globetrotting. He had his wit about him and was worldly-wise in the manner he negotiated borders, bureaucracies and the intersection of global affairs and local politics.

For some context, a few months ago, another Nigerian explorer pulled off an internet sensation with his motorbike crossing from Europe to Nigeria, with the highpoint being the treacherous Sahara leg and the comic reliefs provided by the bon vivant image that Kunle Adeyanju cut in his photographs with women across West African (his work with local civic organisations was almost lost in the more salacious hubbub). Àjàlá’s travels are all of these writ large, in their drama, geographical coverage and a crosscutting cast of characters with whom he made acquaintance.

He might have been riding a colourful scooter, plastered with graffiti and memento in a manner only redolent of a dáńfó in the streets of Lagos, but he held court with kings and had tea with heads of governments, mostly with ‘receipts’ to show for it. He met and had a photograph taken with the Shah of Iran. He got Pandit Nehru to ride his bike for show. He held animated discussions with Gamal Nasser and had a formal interview with Golda Meir over tea. Yet, he visited the Australian aborigines and Palestinian refugees in Jordanian camps. He also made sure to look out for and make friends with African students scattered along his route. He had a largely insightful analysis of the situations of these subalterns, navigating the balance between the human conditions of the disempowered and the gamesmanship of political leaders which do not often intersect.

Clearly aware of his privileges, he made sure to pull the strings when necessary, even if he sometimes strained his luck. In a dangerous border crossing of the UN-manned ‘no-man’s-land’ between Jordan and Israel, with no entry visa, his status as a British subject (from colonial Nigeria), born in Ghana, facilitated the coming together of UN, British and Ghanaian officials to break protocol and see him stamped into Israel (a grouching UN soldier of Dutch origin was not impressed that his weekend of rest had to be interrupted to sort out this “brief but explosive furore”, as the Jerusalem Post reported the following Monday). This was only one of his many troubles from which it took high-level diplomatic interventions to extricate him; both Khrushchev and Nasser had to intervene when he was arrested entering the Soviet Union and Egypt.

In Amman, Jordan, he was lucky not to be caught in the attempted assassination, by a bomb, of Prime Minister Majali with whom he had an appointment. He did make a successful appointment a couple of weeks later, and the ill-fated Prime Minister one with the assassins a few months afterwards. Although Ajala enjoyed the generosity of the Jordanian officials in the circumstance, he still went ahead to express criticism of the show trial of the supposed culprits whom he believed were pressured to implicate Egypt and Syria with which Jordan had diplomatic rows. Ajala must be one of the few people who could meet heads of governments across borders in this warring region without being an official peace envoy.

One might wonder why this important book—at once a gripping tale of derring-do and often clear-sighted analysis of global affairs—fell out of circulation after its first edition. The last chapter of the book, which covered the Australian leg of the trip, provides a clue. The author had rested for a while in that country, married a local lady and raised a family. Refusing to publish Ajala’s commentary on Australian society for a reason which is objectively spurious—“it is considered too critical of Australia, and might offend our readers”—a magazine editor rather preferred to publish a feature on his charming adventures, quoting carefully selected portions of the author’s own rejected, original article. Considering how the western media has a lot to say about the rest of the world, one is left to wonder if there was a possible unstated policy of blackballing commentary by third-world types with acute awareness and use of their agency.

Nigerians have the reputation for being quite the traveller. Admittedly, this attribute is now motivated by diverse reasons, some quite more grievous than a starry-eyed sense of adventure. In this era of the social media, the go-pro camera and the internet are also available to give an in-your-face presence to new adventurers. Yet, the new generation is merely hiking in the shadows of previous black sojourners—shadows made even longer by a certain sturdy sense of self. Think of George Thomas, a black American who ran one of the most successful night clubs in Czarist Russia and had to escape to Constantinople (Istanbul) within a whisker of the 1917 revolution and the doom of his elite clientele. Or Agboọlá O’Brown, another Nigerian, who joined the local resistance defending Warsaw against Nazi invasion and is now rightly memorialised in the Polish capital. Àjálá might be more fleet-footed than these other dangerous adventurers. What they have in common is a certain awareness of the world, and their place in it, that is hardly matched by anything one is likely to glean from current travel blogs.

From this perspective, An African Abroad is both an inspiration and a challenge to new generations of Africans making their way through the world.

The new edition of An African Abroad was published by OlongoAfrica.com. It can be purchased on Amazon.com. The Nigerian edition will be out via Masobe Books in December 9.

___________

Dèjì Tóyè is a Lagos-based lawyer, writer, and cultural advocate. He can be found on Twitter @dejitoye.