We drive alongside the 2,512 square kilometre Old Ọ̀yọ́ National Park till we arrive at bustling Bani, in the Kaiama Local Government Area of Kwara State, some two hours from our destination, the town of Bàrà, the most active archaeological site in Nigeria.

Bàrà falls outside the boundaries of the National Park and so is unprotected against new and persistent threats to this site of priceless heritage. This despite the huge historical significance of Bàrà and its close association with the old Ọ̀yọ́ Empire capital, Ọ̀yọ́ Ilé, which is located within the park.

Bàrà’s agrarian air belies its past as one of the most important centres of the 17th-century empire, one of the largest in West Africa, stretching from some parts of present-day Nigeria to Togo and the Republic of Benin. The vestiges of this great history, embedded across the landscape of Bàrà, are the reason this 1.92km in diameter site has seen more than 50 archaeological digs in recent years.

“No other place in Nigeria has received as much excavation as we have done here,” says Akínwùmí Ògúndìran, Chancellor’s Professor and Professor of Africana Studies, Anthropology and History at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, USA. He is the author of The Yorùbá: A New History, published in 2020. The archaeologist was first introduced as a student to Ọ̀yọ́ Ilé and its environs in the late eighties by his teacher and mentor, Babátúnde Agbájé-Williams. Now Ògúndìran leads his own team of young scholars (from the University of Ibadan, where he is a visiting professor) on the ten-year Old Ọ̀yọ́ Archaeological Project, which he started in 2017 in collaboration with the Nigerian National Parks Service. The National Geographic Society supports the fieldwork we are here to observe.

On discovering Bàrà and its historic wall some years ago, Ògúndìran and his team paused their work in the related sites of Ọ̀yọ́ Ilé and Kòso in order to focus on Bàrà. They set about systematically mapping the site and collecting data, documenting all relevant features.

“We did that with the intention of nominating this site as a national heritage site, and we need archaeological evidence to be able to make that claim,” Ògúndìran says.

Bàrà was the burial site of the Aláàfin (King) of Ọ̀yọ́, ruler over the empire and its millions of subjects. Many past Aláàfins — including iconic Yorùbá historical figures such as Aláàfin Aólẹ̀, Onisile, Ajagbo and Ọbalókun – were buried here. “It is a spiritual site,” Ògúndìran explains. “When a new Aláàfin was to be installed, the Aláàfin-elect must come here to worship the past Aláàfins. And that’s when he could be recognised in Ọ̀yọ́ Ilé.”

In death, the king would be brought back to Bàrà for the final burial rites. Of those returning with the remains, some would go with the Aláàfin to the next world (the premise of Wole Soyinka’s play, Death and the King’s Horseman, based on a historical event).

Archaeological survey, including the use of Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and the magnetometer, has so far failed to uncover the royal dead of Bàrà. “The site is big; we have only scratched the surface,” the archaeologist says.

In any event, the project is more interested in the lives of those who lived in Bàrà, and the material culture they left behind. According to Ògúndìran, “Bàrà was more than a place where they buried people. It was also where priests and priestesses who would administer to the king in the afterlife were resettled. Some of the wives from the palace, some [courtiers], would be relocated here, and there would be servants attached to them, to maintain this place.”

One evidence of the strategic importance of Bàrà was the magnificent wall that not only encircled the town but also divided it geographically into two. Built with stone and laterite, the wall rose to about six feet as it trailed its way around, and up and down the twin hills of Bàrà, complete with formidable gates. 6.2km in circumference, it took the project team three arduous years to map the wall.

“Ọ̀yọ́ Empire was built to impress,” says Ògúndìran. The old Ọ̀yọ́ Kingdom had been in exile in the town of Igboho for close to a century before returning to its capital of Ọ̀yọ́ Ilé, circa 1570. This was the dawn of the empire, which embarked on an expansionist ambition, building large towns and cities. Bàrà wall ruins are a pointer to that bold vision; the construction likely took years, incorporated the topography, and required over 500 builders.

“The labour must have been immense, so there must have been a reason. It was not a whimsical construction,” Ògúndìran says. “Without a sophisticated social organisation, you cannot have this kind of large-scale building programme. Ọ̀yọ́ Empire was so sophisticated that they had a minister of survey [to ensure] the walls were built. They had a dedicated palace official for that.”

One of the team’s most exciting discoveries is the site known simply as Bàrà Stone Marker 6 (BSM6), which brings to light small, pre-empire groups living just outside Bàrà’s wall between the 13th to 15th centuries. “When the imperial period began, that’s when the occupation of this site ended,” according to Ògúndìran, who thinks the occupants may have been evacuated to populate the empire’s new towns. Among the discoveries at BSM6 are the fragile remains of an individual that lay buried under a domestic courtyard for more than 700 years, and which may hold the key to “what life was like before empire began.”

The people here could be Ọ̀yọ́ before the Igboho-exile phase, or a branch of their ancestors. What is certain is that they were “a very sophisticated civilisation in the way they made their pottery.” It is not possible to walk a few steps in Bàrà without seeing potsherds, often with intricate designs of old Ọ̀yọ́ pottery – thousands are in situ here.

Also excavated at BSM6 are objects including Carnelian and Jasper beads, a terracotta figure, as well as iron slags, a by-product of iron smelting. As Ògúndìran observes, “It is the agglomeration of materials that have never been seen before, that are not known before,” that makes BSM6 such a discovery. “It will unlock the door to understanding how the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire began.”

The beads offer a window on West African trade history. As Ògúndìran explains, “Although it was a small community, we have evidence that they had a wide network. This area was part of a large regional network of trade between Central Yorùbá (Ilé Ifẹ̀) to the River Niger and all the way to the 14th century Mali Empire.”

Bàrà society inside the wall and the communities immediately outside it in an earlier historical period, encapsulate the stated aim of the project in this location: understanding the relationship among the different people who lived here. This is undercut by new communities that have encroached massively onto the sacred site in recent years, and whose activities are rapidly eroding the historical character of the site and decimating thousands of heritage trees that have stood in Bàrà for decades, even centuries. The alarming loss of tree cover on the site portends an environmental crisis, as desertification creeps in.

Animal grazing, arable farming, and an illegal charcoal industry are burgeoning, posing an existential threat to the site and its huge store of archaeological items. The charcoal making has been particularly devastating. Trees are being killed through pyrolysis, set alight from the roots to fill a growing line of charcoal bags out of Bàrà. Dozens of charcoal pits are on the site, and stumps where red hardwood trees once stood.

And with no sign of a shift in government indifference, the damage looks set to continue. The loss of a major historical site, even as an archaeological project is just beginning to scratch its surface, would be a cultural disaster of unspeakable proportions.

Ògúndìran has called on the current Aláàfin – Oba Lamidi Adéyẹmí III who rules from the present-day location of Ọ̀yọ́ – to intervene. So far, the king, custodian of Ọ̀yọ́ history, is not known to have exercised his moral right on ancient Bàrà.

“All the trees around us are dead,” laments Ògúndìran, who fears the integrity of the site is now so compromised that it can no longer satisfy a claim for official heritage designation. “When we started, there was no building inside this wall. But in the last two years, they’ve built [dwellings], they started farming here. And that process is going to continue in the coming years.”

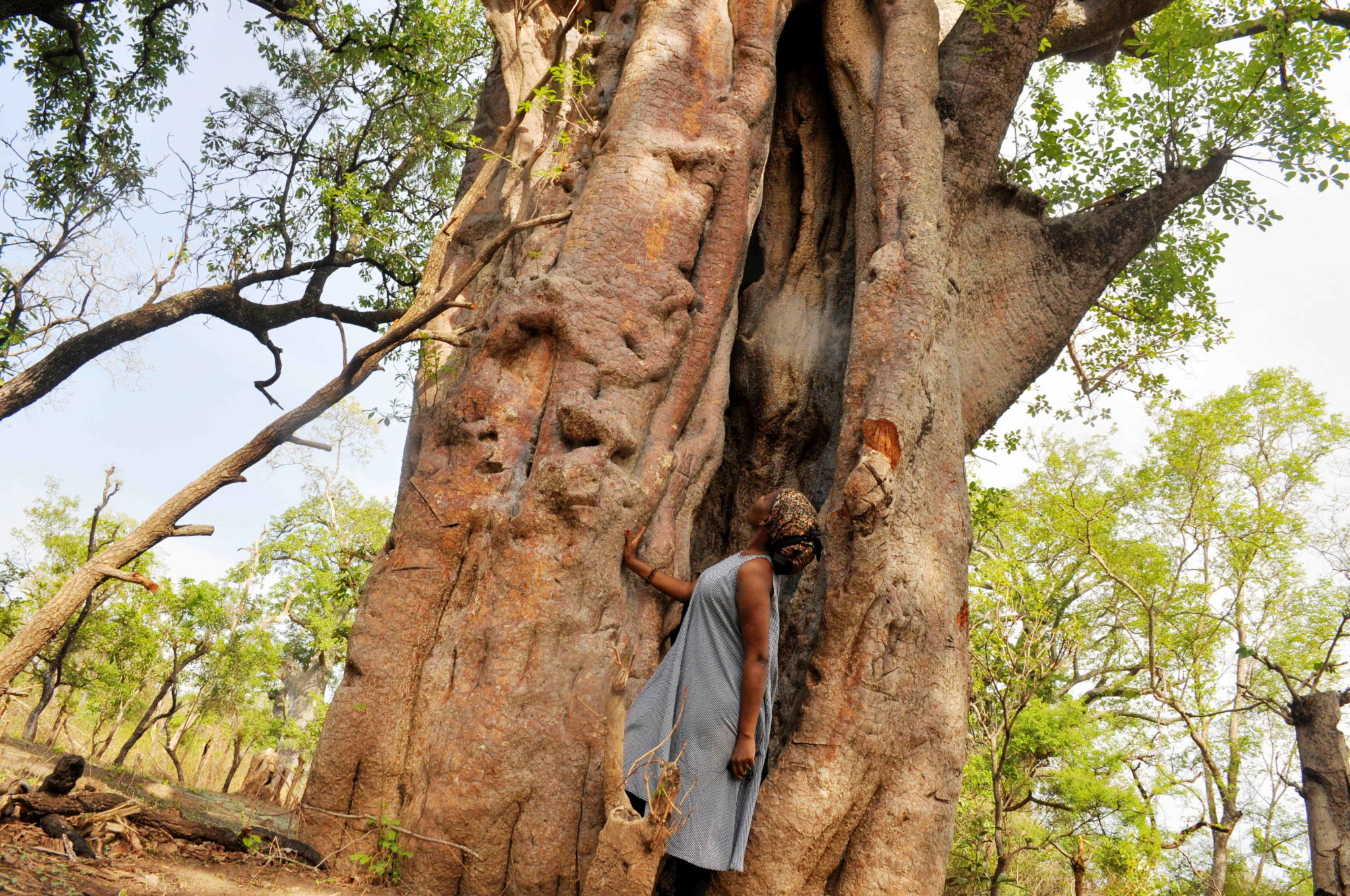

At the start of the project five years ago, the local people revered the site as sacred, claiming to see lights in the baobab tree on the location at night. “But in the last four years, that belief declined because of pressure on the land,” and newer actors have moved in with no regard for cultural and historical heritage. They are also not averse to the occasional sabotage of archaeological work.

“Within a very short time, before our own eyes, things changed as pressure to feed their own population increased,” says the scholar. “This is one of the well-preserved sites that should be maintained, but unfortunately, we were not fast enough. And the way things are going, if nothing is done in the next year or so, I’m afraid…” His voice trails off.

“We are recovering some evidence to tell generations that, at this place, at this time, this is what happened – even when the site is no longer here.”

As the Assistant Director of the project, Olusegun Moyib of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Ibadan affirms, “No excavation is a waste of time. Whether you discover or you don’t discover, you still have a story to tell.”

Molara Wood is a Nigerian creative writer, journalist and critic. She has been described as “one of the eminent voices in the Arts in Nigeria”. Her short stories, flash fiction, poetry and essays have appeared in numerous publications. These include African Literature Today, Chimurenga, Farafina Magazine, Sentinel Poetry, DrumVoices Revue, Sable LitMag, Eclectica Magazine, The New Gong Book of New Nigerian Short Stories (ed. Adewale Maja-Pearce, 2007), and One World: A Global Anthology of Short Stories (ed. Chris Brazier; New Internationalist, 2009). She currently lives in Lagos, and runs the ART for the People Podcast.