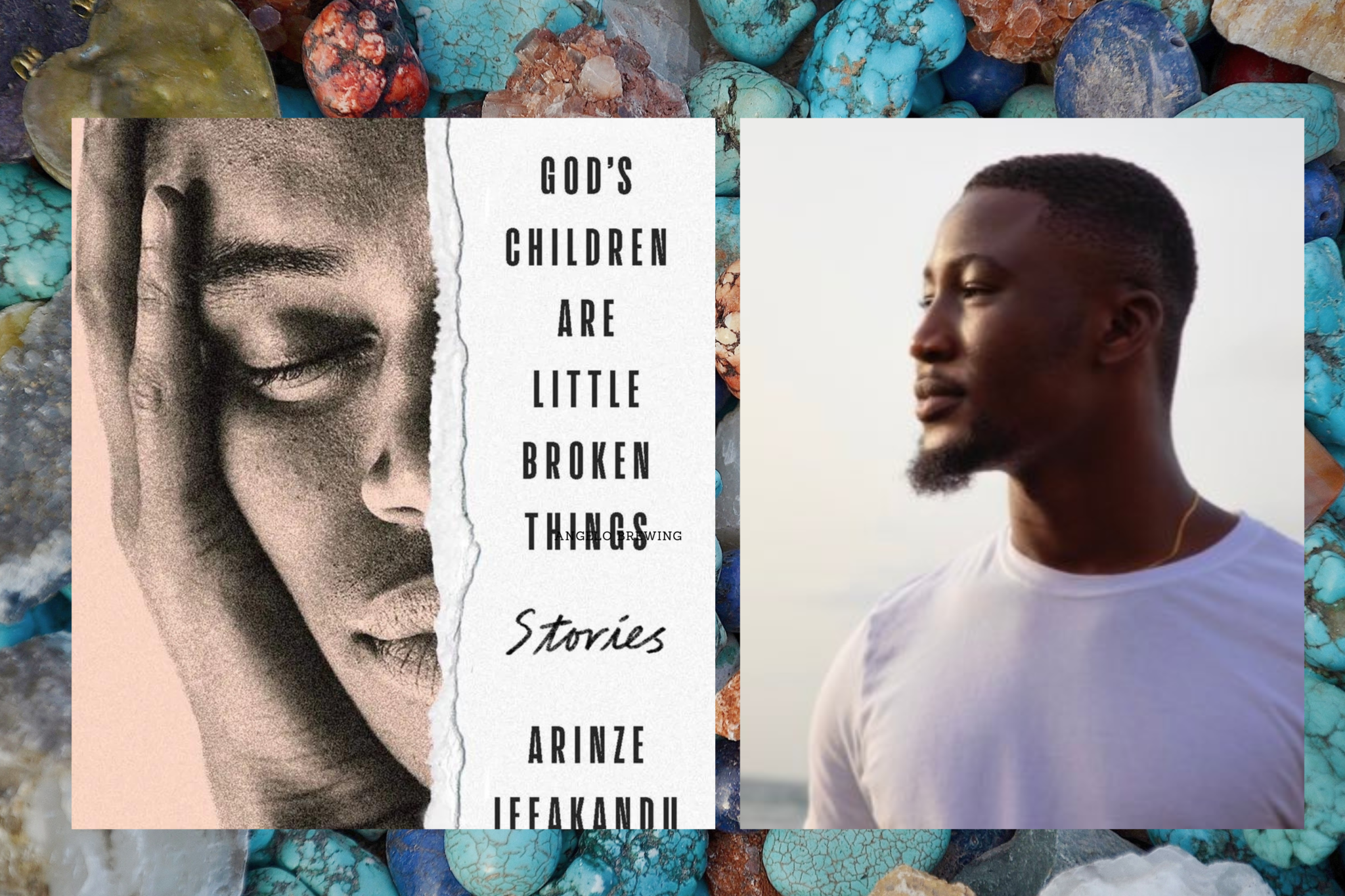

In writing the nine stories in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, Arinze Ifeakandu spent time with each character, keenly observing, asking the right questions, and learning their pleasure, history, joy, and rage. He delicately brought them to life in shops, clubs, bedrooms, and in the streets as they moved through spaces in their unapologetic Nigerianness.

Ifeakandu, in his debut, reveals the mundane and daring lives of gay men in Nigeria, conveying their everyday experiences with compassion. The increasing poverty rate in the country manifests in different aspects of people’s lives, particularly their relationships. The potential lover one might approach, the one completely out of one’s league, and the power dynamics in an existing relationship, are heavily influenced by one’s economic power. This sometimes shapes the interactions of men that Ifeakandu places before us, as lack of money often dictates the (micro) aggressions and indignities people explain away.

“The Dreamer’s Litany,” which launches this collection, explores the frustration of forgone dreams, power imbalance, and navigating beguiling individuals in their deception. A rich, older man visits a shop owner, and continues to do so every night, until he gets what he wants. The cost of holding on to the thread of a long-abandoned dream may be high, but so is forgetting. Can abusers smell this dissatisfaction, this longing for another life, on their potential prey and snoop around until their breaking point?

In this story, Ifeakandu shows how language can shield one from the meanness of the world and how it can also make one vulnerable, open to kindness. He writes: “They spoke in Hausa, and the more Chief came to know about Auwal in that language, the more Auwal wanted to share.” The story signals the reader to see that the languages chosen in specific contexts might not only be for verbal communication, that one may connote enmity, the other endearment. Between Chief and Auwal, English is the cold, distant language, while Hausa is for intimacy “…he’d not expected Hausa to be, for this man, a language of tenderness, he’d expected it to be a language for business, a language to be used and discarded and reused.:

With a tender and confiding narrative voice, Ifeakandu draws the reader into the lives of the characters. Worthy of note is the way he seamlessly weaves the past into the present, present into the past, without losing the reader. Memories unfurl with precision. And isn’t that what a good story does, absorbing the reader as they breathe and feel with characters? He employs interesting techniques such as measured commas and repetitions to evoke emotions. Apart from sudden section breaks which might be a bit confusing, the pages of this book are filled with rich sentences and metaphors like “your body was a well in dry season, deep and empty and full of cavernous echoes.”

As much as the stories are about people simply living in their imperfections, they’re also a commentary on the politics of the Other. In a wildly homophobic society such as Nigeria, these stories highlight the many ways the laws empower people to be cruel. The Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act 2013, signed by former president of Nigeria Goodluck Jonathan, has emboldened many, leading to fatal consequences such as lynching gay men or public advocacy categorizing same sex as heinous act. “AlỌbam,” the fifth story, makes one ache in a specific way for those terrified to simply be. “This country eats people alive, and only the strong and sharp can make it.”

The intent of the SSMPA bill is to stifle joy and punish queer people for existing. “I am telling you because you are my person, alỌbam, and I know you will understand when I say that I’m worried that his life will be very hard here because of it.” But joy should not be experienced in crumbs. Ifeakandu and Eloghosa Osunde in her recent debut Vagabonds!, probe the structures that empower some to claim their existence valid, and regard everyone else as Other. These writers centre queer people in Nigeria, just as Toni Morrison said and did: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central. l claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.”

Ifeakandu examines the body as a site for different emotions, stretching and bending to accommodate pleasure and violence. He writes of Som in “What the Singers Say About Love”: “Before him, I walked around campus with my body alert, that is what the body does when it has become a recipient of frequent violence, it perks up, an antelope, ready to flee, or a guard dog, ready to pounce.” This story focuses on two young lovers in the university, as one, Kayode, gradually rises to stardom in his music career. They encounter all kinds of aggressions, from friends and neighbors and the world, because their love is supposed to be an abomination.

There’s also heartbreak in these stories. Lots of it. The hurt and quiet rage of a wife mourning a lost marriage, after her husband leaves for another man; of a young man trapped by the trauma inflicted on his body; of a wife mourning a long lost dream; of a boy that is not wanted because of who he chooses to love; of a daughter yearning for connection with her dead father.

Music is itself a character in this book, present at different points, bearing witness. Music, loud and soft, booming from speakers, from a lover’s lips. Popular Nigerian artists such as Olamide, Tiwa Savage, Mr Eazi appear in the stories with their vitality and eroticism. There’s a consistent theme of sensuality. Pleasure, big and small – sex as a valid means of expression. It’s not common for Nigerian writers to dwell on sex scenes. They hint at it and leave the rest to the reader’s imagination. In God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, sex scenes are painted in detail. Passionate, steamy, bland – they exist. Ifeakandu shows you because he wants you to see, as though saying “why pretend everyone isn’t out here fucking?”

One of the most heartwarming features of this book is the pockets of unexpected happiness. Not only by the central characters, but also the ones the reader might encounter once. Consider: “Papa Ebuka was yelling Happy, happy, his voice thick with laughter. He must be closing shop. He never closed quietly, even on nights when the street was not bright and loud; he would yell out words, or burst into song, for this life, I can’t kill myself o, his voice, bright and cheery, multiplied by the deep quiet.” Ifeakandu sees people, and this random moments of joy is a metaphorical message to queer people everywhere to let themselves be, despite the systemic powers raging against them. Allow yourself to love, to feel, Ifeakandu seems to say. Give yourself permission to be alive.

Kemi Falodun is a writer and journalist whose work explores mental health, culture, and social justice. Her writing has been published in Catapult, Al Jazeera, The Guardian UK, The Republic and elsewhere. She’s a 2021 One World Media fellow.