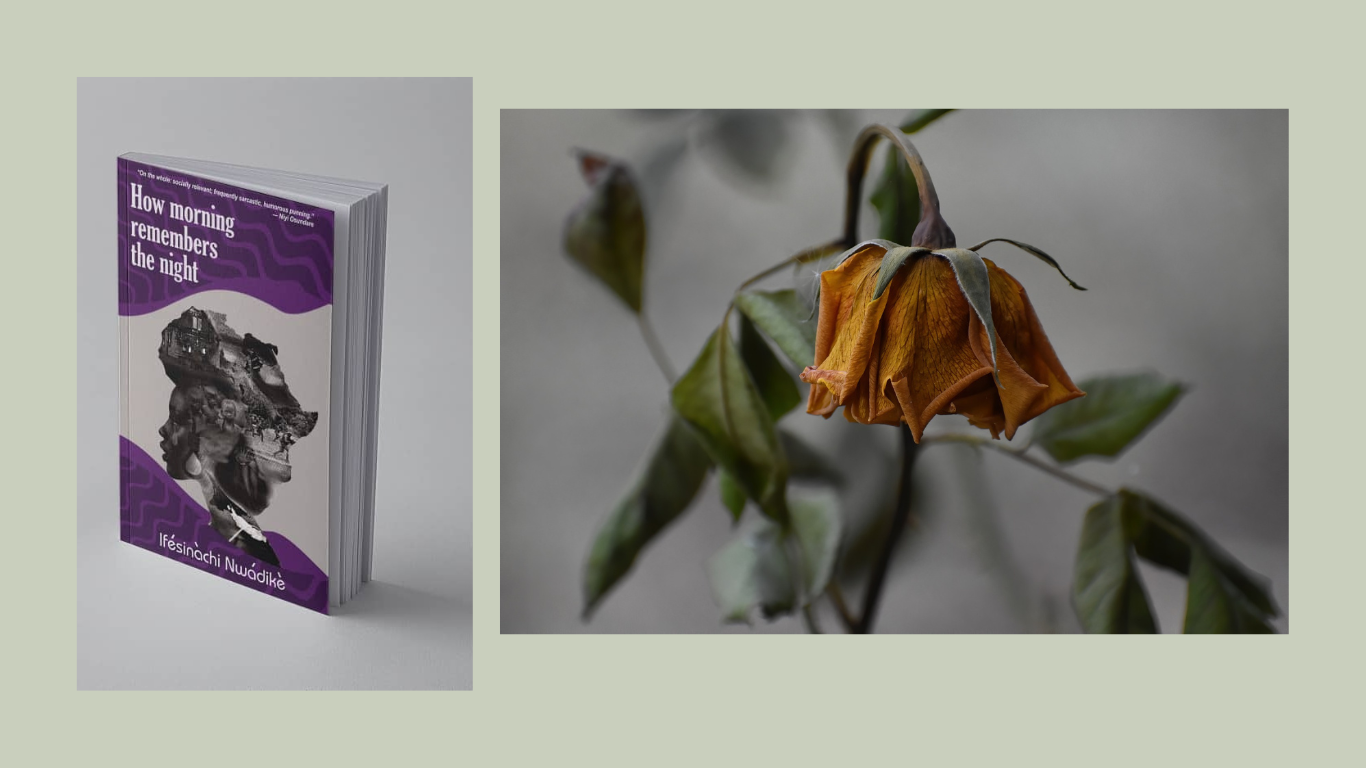

Stirring pain, it would seem, marks one of the textual resonances in Nigerian poetry. This pain, which takes on grief grafted onto memory, for most Nigerian poets, is as personal as it is public. In his debut collection, How Morning Remembers the Night (HMRTN), Ifesinachi Nwadike captures pain-grief and poetics of verdant reminder. The treatment of pain, side-by-side memory as a death pill to amnesia, is urgent and poignant – even now that Nigeria is near a political precipice. Nwadike remembers the Nigerian past for the present and, importantly, for the future direction. How Morning Remembers the Night as co-texts of pain and grief, pursues the notion that there is a sense in which Nwadike reflects and re-enacts Pierre Bourdieu’s Habitus. Habitus is a sociological construct inhered in any individual’s or group’s attitude or habit. HMRTN re-narrates pain and grief and redirects the reader to the maps of personal and public awareness that it offers.

Nwadike’s poetry connects with what I call the Signifying Chameleon. The Signifying Chameleon is the frame of poetry which uses folk motifs as a style blended with contemporary aesthetic currents (multiple, oral texts and radical techniques). This is seen with the changing text and textuality in the collection. The poetic turf signifyingly portrays the tragic territory of a country, as the sodden entrance into the collection mapped “A Deluge of Grief” by the poet-persona encodes: “These landscapes I paint are the terrains of a mind disfigured by pain.” The opening here invites us into the grim and parlous experience of the persona’s country, Nigeria. Amnesia is akin to the Nigerian postcolonial condition, and it is deliberate. In the introit, Nwadike recalls a rude awakening of memory as it “came knocking on my heart’s door/with sorrow stained knuckles/barging in,/ they embraced the bosom of my soul.” This grief, like John Donne’s apostrophized “sun,” fits the “busy old fool” (Donne’s Sun Rising), which intrudes on the persona, carrying nothing pleasant and heart-warming. Still, it permeates the country: “wrapped in the anguish of fellow countrymen/ buried in coffins levitating in the sky/ laid bare on the highways and roadside carnages.”

There are instantiations of grief and mourning in poetry and at no phase of history in literary imagination is grief absent. Nigerian poetry is deeply grief-toned. Particularly worthy of mention is Nwadike’s powerful reflection on the subject of death and allusion to the event, the near mob justice recorded of a harlot in the Bible “He that has no sin/Let him cast the first stone.” The vengeful inclination of man to shed blood is not governed by moral restraint but by “…The hates in their heart/ Stones of hate/ Inhuman sticks, sadistic tyres….” In a very direct language that rifles through the social anomaly, Nwadike, like an activist poet, decries the Aluu jungle justice, which claimed the lives of four young promising undergraduates of the University of Port Harcourt in 2012.

Nwadike’s poetics kindles memory and narrates the recent upsurge in child abuse cases and mindless violations of child’s rights. A grim, graphical retelling accompanies “Death Came Calling in the Guise of Pleasure.” This is evident in “each line is a loaded venom/stung into the heart of paedophiles/who relish the mastication/of unripe fruits.” The lines relate to the anger the persona feels about the rape and killing of the thirteen-year-old, Ochanya Ogbanje. In taking the sable of memory further, Nwadike deploys what I call the “regenerative prism of grief.” This also connects to the Signifying Chameleon pointing to the spate of insecurity in Nigeria. In “Purple is the Colour of Mourning”, apart from the symbolic appropriation of the Catholic grief sign, purple, there is the activation of some sort of national memory, the well-documented Leah Sharibu ordeal in the hands of Boko Haram insurgents. The insurgents, who, as reported in the dailies, intended that the young Christian girl would convert to Islam as a precondition for freedom. The persona in the poem calls rage to pinpoint and display the grief and dirgic inspiration caused by oppressive agencies of non-state actors. The voice is laced with anger and frustration, as obvious in “From this hell-hole of anguish/ Dug by sectarian arrogance/ comes this song of grief.” Fury against national amnesia finds strong invocation in Nwadike’s debut collection.

In most circumstances of pain, as recurring history apart, the more lethal grip in Ifesinachi Nwadike’s Nigeria is the amnesia wrought when pain is a plus and minus habitus, pointing to Pierre Bourdieu’s term, which captures what refers to as hexis, meaning the tendency to hold and use one’s body in a certain way. This concept embraces such things as posture, accent and more abstract mental habits, schemes of perception, classification, appreciation, feeling, and action. Habitus, as Bourdieu posits, does not designate mere practices, although he admits that it is a collective reference to the social group to which one belongs. Its influence, be it intuition or mannerism, as circling any society or place, is inevitable. The minus habitus, I should add, relates the untold experience of unforced pain and losses that Nigeria permits almost too often and subjects self to. Now, the tendency is not to ask questions about the abject condition of this postcolony. This is not so with Nwadike’s poetry. For, in textualising pain, grief and amnesic pain, habitus, as undersigned in HRMTN, is a plus in that he makes his tongue “a compass/ in the sky of remembrance.” This amnesic nudge is important as habitus activates the past to chart the future. Nwadike’s poetry, therefore, assumes the coda against amnesia. This is vivid in the poems where history and memory take precedence.

Shifting promises at electioneering seasons by politicians and deferral of hopes find thematic depiction in “Vision Infinity.” In the poem, the clarity of pain from mangled history with the tendency to remain in the doldrums pricks the persona who appropriates the verdant reminder. In “Who Says We are Corrupt?”, the ironic texture similar to Femi Fatoba’s “Who said I abused the government” reveals the politics of chicanery, pumpkin, carnivals and gnawing corruption with varying phases ripping off the country. The mandate that Nwadike gathers in his poetics, which I call the “field of excoriation”, relates to a force that drives memory. This aligns with Bourdieu’s Habitus, which questions the defection to amnesia in a country where active memory should be a signboard for responsible and actionable leadership. Language, couched in rage and grief, assumes the tool for probing amnesia in Nwadike’s poetry.

In HMRTN, we encounter language in its chameleon poetics, folkloric or griotic gongs, as well as light and humorous movements of texts in such tissues of hair-splitting metaphors and “bombastic ironies.” Such clusters of images, corresponding pace, rhythm and mood convey assorted memories – personal and public – in the poetry of Nwadike. In the poem, The Drum’s Tempo Has Ebbed,” which is a tribute to Ezenwa Ohaeto, a renowned poet of the second generation whose poetry focused on Nigeria’s political governance, Nwadike calls on such visceral images, combining local images and stylistic technique, for instance, the chameleon sign, “coal” which he says has “sealed the minstrel’s lips” and another shocking, sardonic play on figurations reads: “His tongue, stuck in the cave of his jaw;/shame to dehydrated palates.” As a way of dramatising how important Ezenwa Ohaeto is to both the personal and public memory that Nwadike offers, quite indicative and striking is the mythic reconstitution of the poet at his demise, “A boil has grown on the brow of the sky, the moon has gone blind.” It would appear that Nwadike, by deploying the metaphors of boil, sky, and moon, concatenates signs towards the chameleon memory and its witness – Ezenwa-Ohaeto. The earlier line: “shame to dehydrated palates” is the vitriol directed at the gatekeepers of the amnesiac country. This poem reveals the seething candour that is as forceful as it is chameleonic, combining tropes to demonstrate a tradition of folk myths and Western textual techniques. The Avant-gardist tenor finds its course in HRMTN.

This Avant-gardist posture is palpable in a tribute to the Zimbabwean writer, Dambudzo Marechera. Nwadike draws from the postmodernist temperament of Marechera. Nwadike retains African oral tradition and upturns it also in palpable ways. The old Igbo culture of tributes weaves through age and the wisdom that it incubates, but not those, the irksome sons be smeared as “efulefus.”In celebrating a new “madness” confronting conservative writing and narrow-mindedness, Ifesinachi recalls an important voice in African literature. The manner he does so reminds of Marechera, such fiery, theory-upturning iconoclast, the toast of postmodernism in “Flying Plates and Bottles”, and it reads and reeks of this image of life, loved and hated both ways by conservatives and children of that other African Avant gardist world: “Your mind was the mill/where madness, dreams,/and nightmares coalesced into schizophrenia..”

Finally, in the bid to remember, it is evident that Nwadike offers an acerbic retelling of, and virtualization from, amnesic pain and debilitating postcolonial problems that beset Nigeria. Nevertheless, he invests some redemptive light on the future where forgetfulness will be a museum of pedagogy, and the dark chapter of Nigeria, awaiting closure.

Poet, emerging literary critic, and theorist Ndubuisi Martins (Aniemeka), has published two books of poetry: One Call, Many Answers and Answers through the Bramble (Longlisted for the Inaugural Pan African Writers Association Prize for Poetry, 2022 (English Category), and also co-edited 22 Voices for WPD (a World Poetry Day E-anthology of poems, 2022). Mr Aniemeka is on the Advisory Board of The Protagonist, the Literary Journal at Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic. He is the Publisher of Peaquills Review.