Shortly after the lockdown began in March 2020, I began buying more books.

This started innocently perhaps facilitated by boredom; there were some new titles that had just been released that I wanted to read. Some were books of writer friends I was interested in supporting or reviewing. Others were titles I had come across on my favourite late-night shows I wanted to engage with. In a few days, my small collection at home in Central London had grown from a handful of relevant books I had acquired to help in my research to something larger than my shelf could contain.

That was the beginning. I then started discovering, online, some titles I’d heard about for years but never read, or never owned, or never had enough money to chase. Some I owned in the university but lost due to friend ‘borrowings’. Some I came across when we were growing up, but lost sight of over the many years of moving. Four years ago at a literary festival in Kaduna State in Nigeria, for instance, my tote bag containing a first edition copy of An Example of Shakespeare, a collection of literary essays by J.P. Clark, with my father’s signature and the date he gave it to me as a gift, was stolen while I was getting lunch. I was pleased to find another first edition online as replacement, even without the sentimental value of my father’s signature. There were books by Cyprian Ekwensi I had read as a kid or even owned. And then there were the Achebes and Tutuọ́lás. The compulsion to buy these books for their sentimental value eventually overtook the earlier desire to merely re-read them.

As a child, I experienced great joy from my father’s book collection, in Yorùbá and English. At thirteen, he handed me his copy of The Complete Works of Shakespeare and convinced me to read a few of the works he had enjoyed. It would be years before I was ready for the plays, but I loved the poems, which influenced my first attempts at writing poetry with end rhymes. Harold Robbins, James Hardley Chase, Adébáyọ̀ Fálétí, Bámijí Òjó followed, bringing with them a sense of rootedness in something magical and enduring. I remember too the thrill of occasionally stumbling on a gem of a book at a roadside thrift bookseller (we called them Bend-down Bookstores) on the streets of Ìbàdàn, where I bought my first copy of Surely You Must Be Joking, Mr. Feynman, for something less than one cent. It was my most valued book for a long time. Another was Czeslaw Milosz’s Visions from San Francisco Bay. Through books that defined the memory of my growing up, I travelled to different parts of the world and developed an attachment to the physical books as well as my memory of places I never visited.

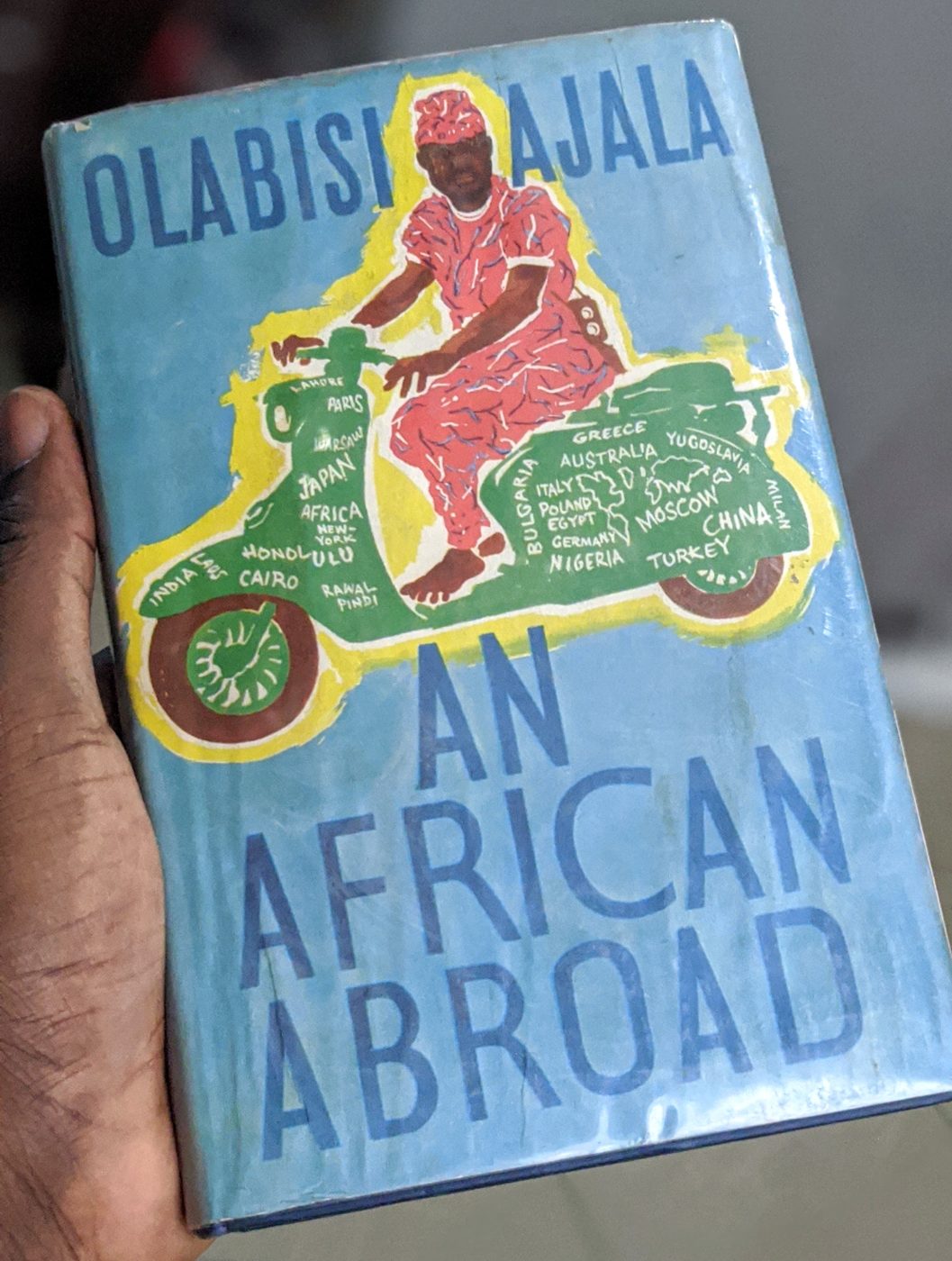

One of the books that would become part of that obsession itself related to travel. “Àjàlá” is a Nigerian slang word for a frequent traveller, made famous by a memorable ditty by Ebenezer Obey with the lyrics, “Àjàlá travels all over the world” but also by Mashood Ọlabísí Ajàlá for who the song was written. He was a Nigerian student in the United States in the 50s whose fame grew to reach not only his family back home, but heads of state in nations around the world including Israel, the then USSR, and India, whose leaders he eventually met. His trips around the United States earned him friendship with then Governor Ronald Reagan who helped him get a Hollywood role. His subsequent trips around the world, on a scooter no less, brought him into contact with Golda Meier, Nikita Kruschev, the Shah of Iran and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, each encounter with its own fascinating, daring story, recorded in his memoir An African Abroad (1963). His name in Nigeria became permanently associated with any citizen with restless legs.

As I grew up, I had heard about this memoir for so long, and looked for it everywhere, with no luck. If my father had it, I never came across it in his array of books that were eventually destroyed by a rainstorm. The book had gone out of print by the time I became an adult, and existed only as scanned PDF copies online. Everyone I spoke to who’d once had the book had ended their story with an eventual loss. My searches on eBay and Amazon led nowhere, and I eventually gave up. I eventually read the story through a PDF scan a researcher had sent to me, but I was irked by the realization that I would never lay my hands on a copy.

J.P. Clark’s America Their America, a caustic memoir of the author’s time as a Parvin Fellow at Princeton in 1962, was another book that had long fascinated and eluded me. Clark had been dismissed from his fellowship on account of his restlessness and distraction. This book and Àjàlá’s offered complementary perspectives on America as well as early portraits of an emerging Nigerian professional class confident in themselves and unafraid to buck orthodoxy, speak their minds, document a foreign country in its imperfections and complexities, and project Nigerian excellence. When I became a travel writer on my first trip to the United States in 2009, I had these names in my sight as important guideposts. Later, I discovered Mbonu Ojike, who had been a student in the US in the 1930s himself, and whose two volumes My Africa (1946) and I Have Two Countries (1947) might have actually laid the groundwork for the work of Àjàlá and Clark in travel writing and fearlessness of voice.

In 2019, I got a fellowship to the British Library, to work on African language book collections from the 19th century, and an opportunity opened up to check up the Library’s record of Ọlábísí Àjàlá’s book. It was easier than I thought. It took a few minutes to find on the British Library’s website, and a few minutes more to arrive at my desk on the third floor, to much relief. There it was, in the pine blue hardcover, in my hands at last, as if it had not eluded me all my life. I marvelled at how many more of it were now lost to private and public libraries, rot, and publisher acquisitions. Jarrods, which published the book, had folded up or had been either bought over or merged with another publishing outfit. The rights to the book had also either reverted to the author’s family (scattered around the globe) or belonged to the new publishing outfit that Jarrold’s became, and thus out of reach for new prints. Clark’s book, though, was less scarce, the author being alive, and I eventually found a copy to buy when it was republished by BookCraft in Nigeria in 2016.

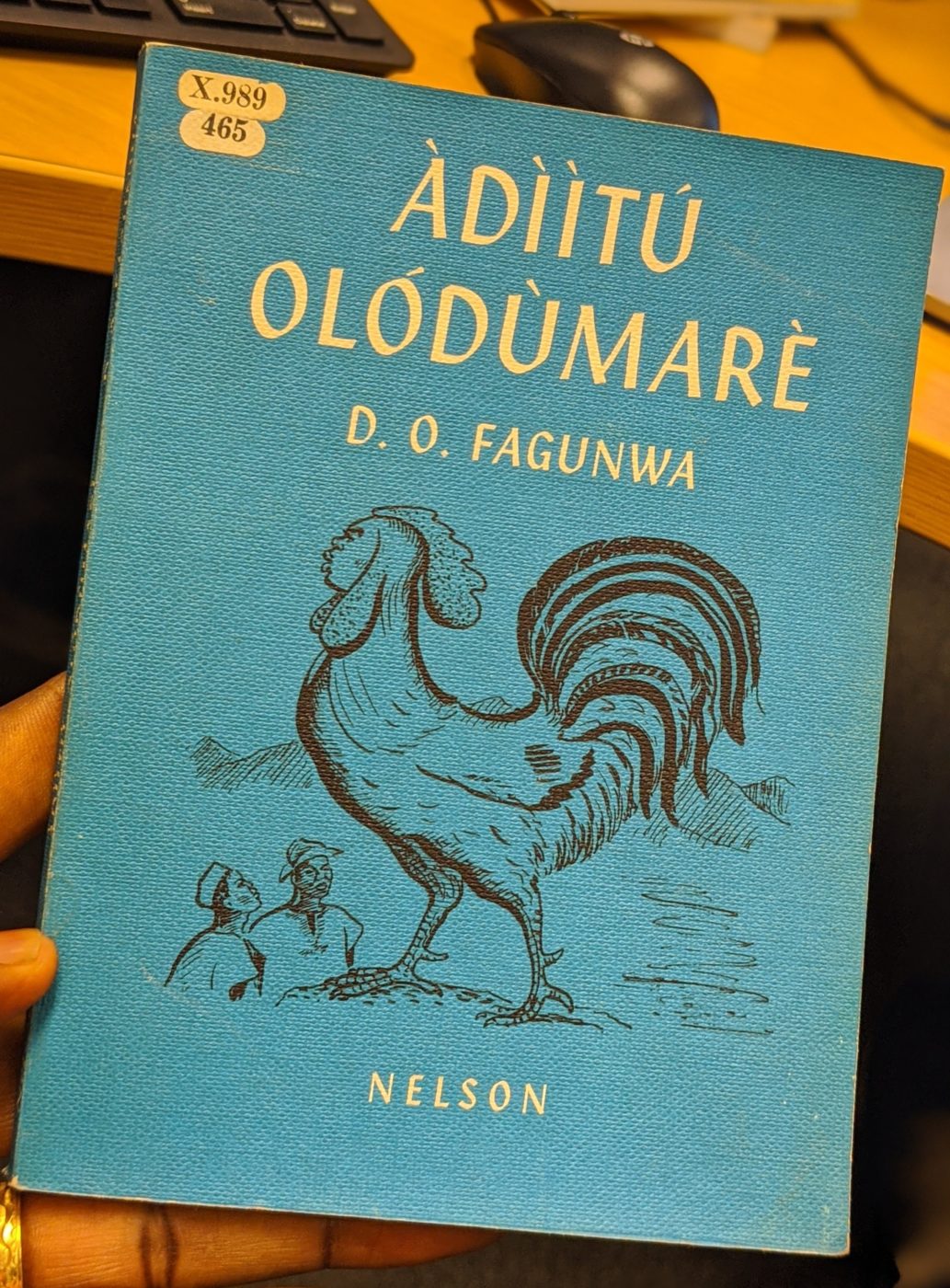

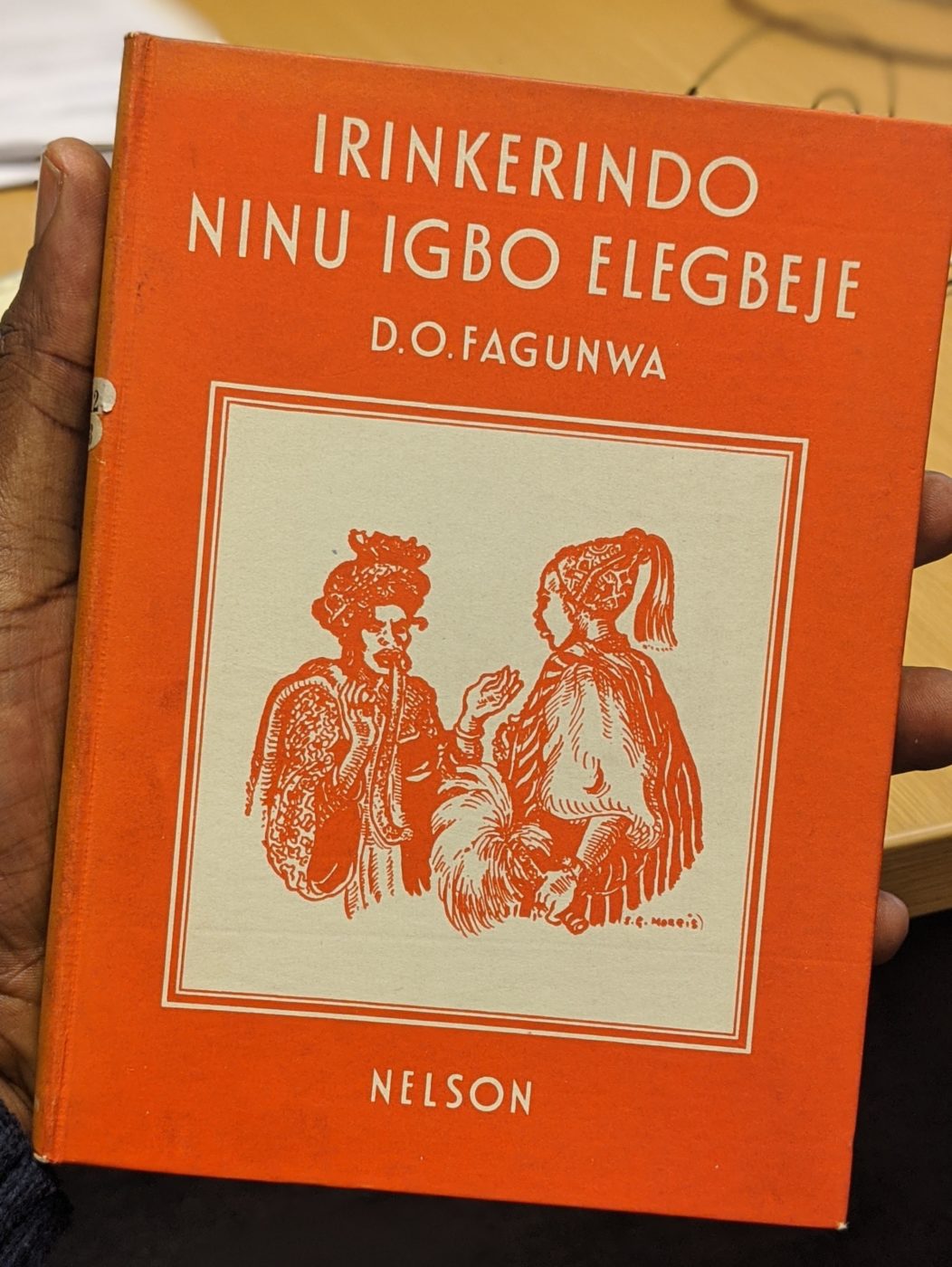

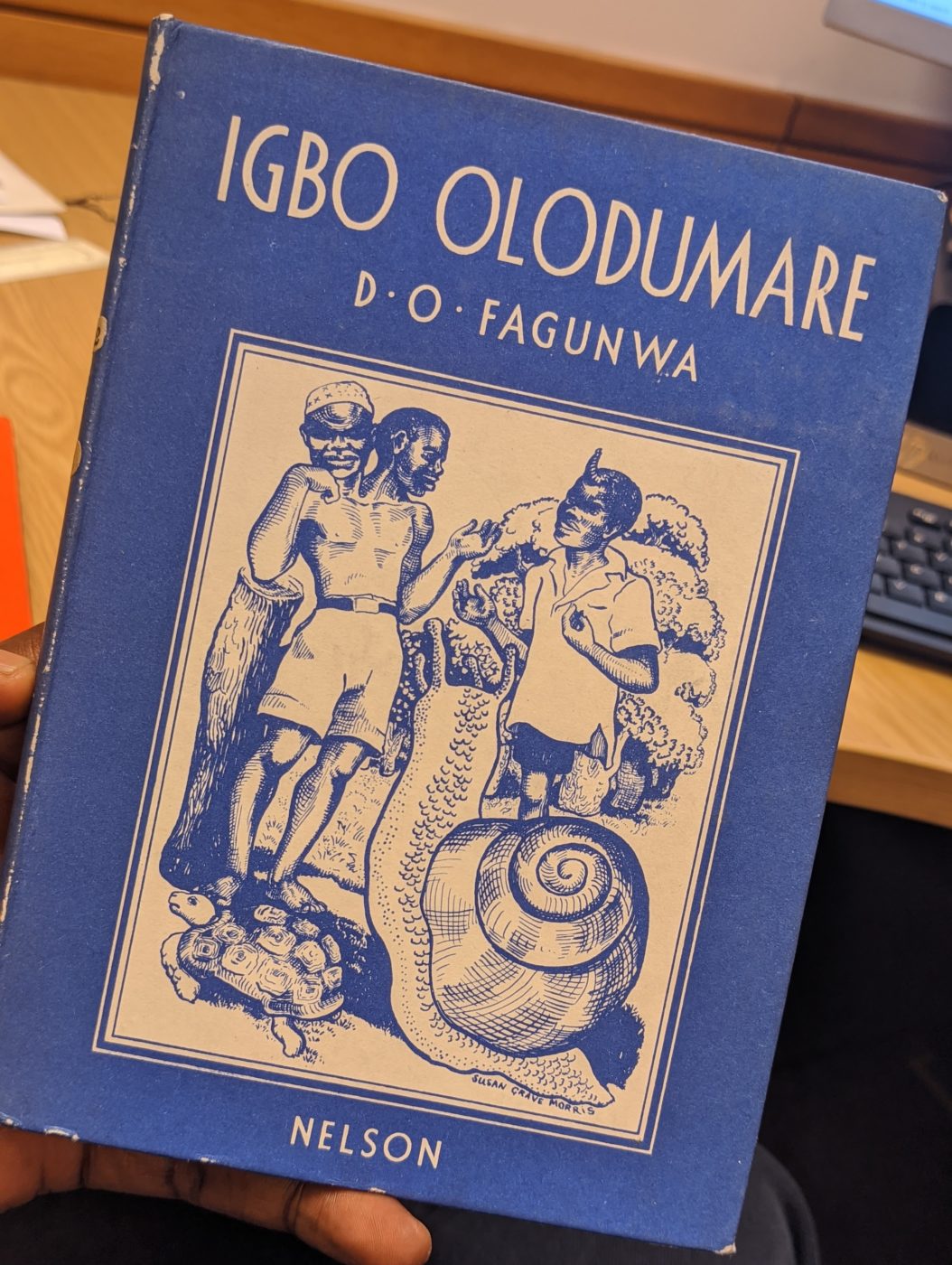

Throughout the months I lived and worked in London, I would go through moments during the day’s work, when an old Nigerian book title would come into my mind, I would rush to my computer to order them up to my desk. In ten minutes, it would be in my hands, and I would savour the pleasure of reuniting with something that was, just a year earlier, so rare and unavailable while mourning the fact that this secure place, here in London, was probably the only place one could still see and touch it. Sometimes, it was just the sentimentality of the cover art — the five novels by the famous Yorùbá novelist D.O. Fágúnwà, for instance, have been reprinted over several years, but the original cover art, with intensely animated fantastical characters some drawn by Bruce Onobrakpeya, can no longer be found on subsequent editions. Other times, it was just a desire to reconnect with something I had last seen in my father’s study in Àkóbọ̀ Ìbàdàn as a child and took for granted.

Books published by the Mbari Publishing collective in the early sixties, work that documented some of the first creative outputs of writers who went on to become prominent names in African literature, are also now very hard to find anywhere but Western libraries (usually far away from Africa readers) and private hands (usually hard to track). Neither are copies of Okike, published by Chinua Achebe when he moved to the University of Nigeria Nsukka in the 60s, or those of Black Orpheus once edited by Wọlé Ṣóyínká. I began to wonder what it would take to build a private collection of these rare books, for myself and friends, but also for posterity, now that it seems impossible to access them without first visiting a Western country.

I returned to Lagos briefly in October of 2020, and immediately went around the National Library of Nigeria hoping to find details about the process of documenting books published in Nigeria. The Nigerian National Library is the equivalent of British Library, only that it was founded in 1964, a good nine years before the British Library was established. What I found was dispiriting, even though, on paper, five or so copies of every book published in Nigeria is supposed to be collected and stored in many of the Library’s facilities across the country, it is usually not the case. Books published from the 60s to date are more likely to be found abroad than in any of the National Library’s facilities either because someone had smuggled them out of storage and sold them to a collector, or because the library had not taken good care to keep track of borrowers. Or, even more likely and dispiriting, because the books were never stored in Nigeria in the first place. The Legal Deposit law, through which all books published in the UK (and all the British Colonies) are obtained and documented at the British Library, also exists in Nigeria and technically empowers the National Library to have a physical copy of all the books ever published in Nigeria. But it has not always been diligently complied with. After visiting at least two branches of the National Library in Lagos and Ìbàdàn, I returned to London in low spirits. Not only were there no records of many books I had sought, but there was also no modern way till date to track even the current holdings in the library or at the National Archives in Ìbàdàn which supposed had more materials of value.

I trawled the internet and bought all first editions published by Mbari I could find, from Okigbo to Achebe to Ṣóyínká to Clark.

***

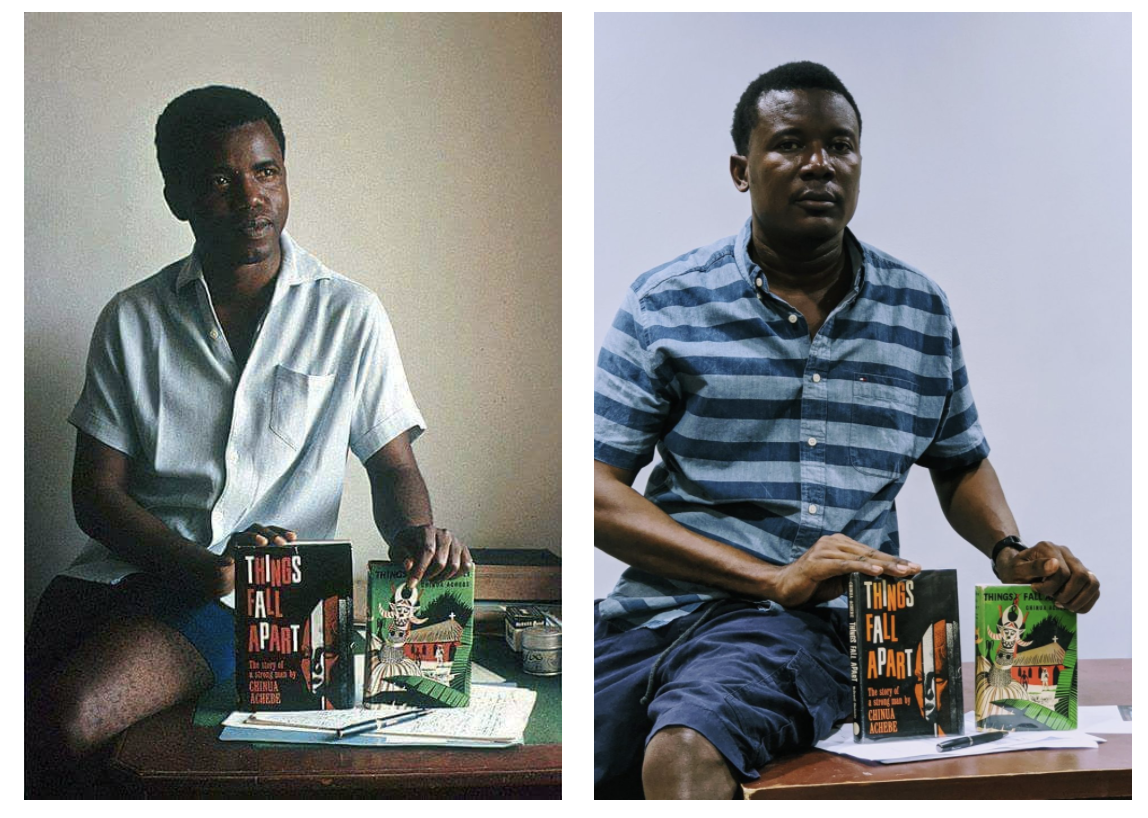

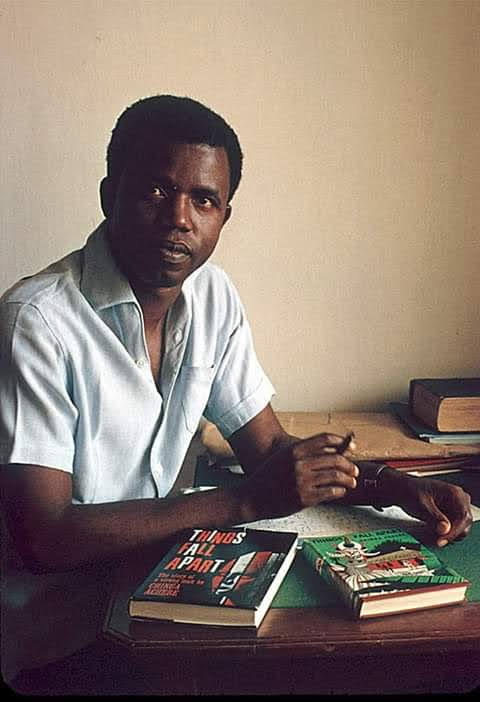

A few years ago, before the obsession escalated, Abby, a friend, had pointed me to a link on eBay where a book had been listed which she wanted to buy. The book, listed for $1200, was Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. It was the very first edition, published by Heinemann in 1958, one of only 2000 first issues, with a green dust jacket. “Can’t you buy one for $10 like everyone else?” I wondered. “You won’t understand,” she replied, laughing. She bought the copy and I forgot about it. About two years later, she called me again ready to sell the book, this time for £2500. In a few hours after the book was listed on twitter, another private buyer had picked it up, and it was gone. The current listing of that same version of Chinua Achebe’s debut novel is $4,491, with a signed version going for much more. A signed American edition of the same book, published in New York by McDowell Obolensky in 1959, is now listed on AbeBooks for $5000. One can find an unsigned one for as low as $2000 on eBay.

I had begun to learn about the underground community of collectors, sleuth buyers, and traders, and about a disturbing disparity in the pricing of books by certain authors — usually authors of colour — and Western ones. A first edition George Orwell book Burmese Days cost $25,000 on eBay. A first edition V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas (1961) cost $1,384. The most expensive Achebe is a signed first edition of the American version of his first book, which goes for $5000. The difference, sadly, is not scientific. The most expensive signed first edition of a novel by Toni Morrison on eBay today is Song of Solomon, cost $895. It probably went up after she died. The most expensive book by Wole Ṣóyínká is a signed version of his prison memoirs The Man Died (1971) which goes for $850. Books by more contemporary authors are not as costly, perhaps because they are still here. The most expensive edition of a book by Nigeria’s Chimamanda Adichie on eBay is a signed copy of her second novel Half of a Yellow Sun (2003), which goes for $600, is in a special slipcase, and is one of only 250 copies produced. Rarity + signature = value. All of a sudden, all the time I’ve attended events with globally-recognized writers and declined to get their signatures on my copy seemed like lost opportunities. But while, in some way, the cost might explain why mostly foreign collectors have our books. It doesn’t explain why book collection is not more of a habit of the successful Nigerian elite.

Occasionally, though, one stumbles on rare gems for a relatively cheap price. The recession caused by the pandemic has perhaps created a whole group of erstwhile book hoarders now in need of quick cash. So thrift book markets all over the UK, and perhaps US, occasionally throw up rarities that get swept up in just a few days online. The other day, I found a rare uncorrected proof Arrow of God by Achebe. Another time, it was a lone issue of Black Orpheus. One day, Abby projects, rare African classics will become as hot as foreign ones when more people pay attention and realize what a lucrative market exists there.

And yet, agreeing that a first edition copy of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s debut novel Weep Not Child (1964) which went for $250 when I bought it late last year was “cheap” is not a fact universally acknowledged. In Nigeria today, that was large enough to be someone’s salary. When I taught at a high school in Lagos from 2015, I earned less than that in salary, so book collection will be seen by many as a rich person’s vocation. A signed version of the same book, on Abebooks.com, where one can still often find rare books, goes for about $3000. For a writer of his stature, and in comparison to writers of different colours with his type of exposure and acclaim, Ngugi at that price is also a steal. But while I do not have $3000 lying around to buy the listed edition, I have the writer’s email address, obtained from a chance encounter at a literary festival in Abẹ́òkuta. His signature on my hardcover copy turns a modest purchase into a future public auction bestseller, a worthy inheritance to pass on, or a valuable private collection item.

In September 2020, the National Library of New Zealand made news by opening its doors to auction about 600,000 rare ‘foreign’ books that were said to be taking up space and costing the country money. Abby swore that most of the first edition of Nigerian literary classics are there Down Under, where book enthusiasts had bought them from Nigerian students who must have brought them there when they dispersed around the world in search of education and the golden fleece. “It’s likely that any new rare book you find online is being shipped from Australia and New Zealand.” True or not, the last time I bought a rare first edition of Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease, from Australia, via eBay, a glued notation on the index page of the 1960 book read “Presented by the Staff of Egbeoba High School, Ikole Ekiti to Miss B. House on the Occasion of Her Leaving the School for Ifaki as Principal of Girls’ High School. We wish you God’s Speed.” Sometimes, gems like these, and the endless thought possibilities of who Miss B. House was, and how the book found its way halfway across the world, adds some personal touch to the value of the books.

When I bought my copy of A Modern Dictionary of Yorùbá for $250 in early 2015, I did not know that I was picking up one of the last copies online. The work, by Roy Clive Abraham, a civil servant in the Colonial military in Nigeria, remains today the most comprehensive Yorùbá dictionary anywhere, with not just words, meanings, and references, but also information about herbs, traditional beliefs, and local science. The last time it showed up on eBay, it was going for £3,000. Other lexicographical work by the same author, for Somali, Hausa, Igbo, and Nupe are equally scarce, and equally valuable. So are other historical or literary books I find during restless online searches. The signed copy of the memoir of Kamala Harris, the now Vice-President of the United States titled The Truths We Hold, went for a ‘normal’ range of price throughout last year, until she was chosen as the Vice-Presidential nominee, and then went through the roof after her team won the election. It’s now $2500. On eBay one time, I found a signed copy of Sirens Knuckles and Boots by Dennis Brutus, a South African writer who was exiled in Nigeria in the 60s and got the work published by Mbari, under the direction of Ulli Beier. At another time, the title was Jagua Nana (1961), a rare first edition I found in 2019, signed by Cyprian Ekwensi and addressed to a friend who was visiting Nigeria at the time: “To André,” it read, “Best wishes to your new venture in Nigeria. From Cyprian, Lagos. 9th April 1962.” A writer friend of mine whom I told about the purchase exclaimed. “I was friends with his kids when we grew up in Enugu. If I’d known they would be this expensive today, I would have got him to sign some first editions for keeps!”

***

I returned to Lagos in March of 2020, just six months into my British Library fellowship, to continue the rest of the fellowship virtually. Many of the books I bought there were left in a safe luggage box, stowed away in a colleague’s office at the British Library awaiting my return. But in Lagos, I did not stop trolling the internet in search of new editions, both for my own pleasure, and an obsessive pursuit of a future private-public collection of rare African classics. If the trip of these books from the dusty shelves of their sellers’ houses did not bring Covid19 to me at home in Lagos, I might survive to show them off someday as the result of a private reparation project. During quiet moments, I come to appreciate what Ṣóyínká had described as “an obsession” when he began to collect African arts in the 60s on seeing his white colleagues’ enthusiastic compulsion.

A few weeks ago, I wrote to Max Hasler who regularly auctions rare books online, to opine on the market for African literature classics. His response was encouraging:

“Achebe already has a very good following and track record at auction and for the two Ekwensi titles we offered in February, it seems that there is definitely room to grow the market further.”

During the lockdown, I bought more first edition books of J.P. Clark, a character that had begun to fascinate me more and more for his role in the early days of Nigerian literature. I wanted to read everything he had written, so I could pay him a visit and interview him for an author profile, similar to what I’d done to his more accomplished colleague. His first play Song of a Goat was published by Mbari in 1961, illustrated by Susanne Wenger, followed by his collection of poems (titled Poems), featuring some of his most anthologised poems “Abiku”, “Fulani Cattle”, “Night Rain”, “Agbor Dancer”, “Ìbàdàn”, “Streamside Exchange”, among others. I bought A Reed in the Tide (1965), and Casualties (1970), signed by the author and dated April 1976. As an elder statesman of literature, he often showed up in literary events in Lagos and supported the new undergrowth of writing activities happening there.

In August of that year, I obtained his contact and gave him a call to schedule an appointment, both to get some of the first edition books signed, and to have a conversation about his life. He was surprised when I listed the titles of his books I had collected. “Why those ones?” he probed. “Do you know that I have written many other books since the 60s?” I knew he had, but no title rang a bell like his earlier works, which most defined him in his most productive phase of life. I made an excuse for my obsession with his old work and wished away what I thought I heard as a rueful tone of disappointment in his voice, that nobody remembered him beyond what he produced in the 60s and 70s. He gave me a number of more titles with his name on them, and I mentally waived them away into a corner of my memory. We agreed to schedule a meet-up via email, which I followed up on immediately but never got a response.

I followed up a few more times and heard nothing back. The lockdown, I thought, had kept him from meeting anyone, being at an advanced age and vulnerable to infection. But on October 13, 2020, his death was announced to the world by his family. He had suddenly fallen sick and died at a Lagos hospital.

In the middle of 2020, I eventually found a private bookseller with a copy of An African Abroad willing to part with it, for a fortune. I bargained it down to about $516, and he agreed. It always was a kind of African traveller’s bible, containing some of this writer’s example of Nigerian confidence in the global space, rarely to be found ever since. It was, until then, the most expensive I’d ever paid for a book. Occasionally, the thoughts would return about the true value of things, of books, of artistry, or private collections, in a world consumed by a number of other matters. The consolation is not always in the monetary value, but in other things: knowledge, a connection to things past, history, and a means to trace back into history the paths that led us here. I no longer have access to my father’s library and all that it contains. I was, in any case, a part contributor to its depletion. What I have left is a gift to my own son.

Later in the year, when I started to do some research into Àjàlá’s life, seeking to interview someone from his Australian family about parts of his life not documented in the famous memoir, I found out that his firstborn son, Ọládipúpọ́ Andrei Àjàlá (born on January 21, 1953, to an American woman), had died in February 2020 in the United States.

Suddenly, the warmth of old books became the only significant marker for a time no longer within reach.

_____

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún, a Nigerian writer and linguist, is the co-founder of The Brick House, and the editor-in-chief of OlongoAfrica. His collection of poetry Edwardsville by Heart was published in 2018.